- Design Approaches

- Posted

Green Gains

In spite of the obvious emergence of technologies and design approaches to reduce the impact of new build, environmental standards remained poor throughout the duration of the housing boom. Now, a unique combination of political will, smart incentives, and a new market of informed and empowered buyers may be about to change that, writes Lenny AntonelliDespite the supposed importance of climate change and other environmental issues to national policy, low impact development has been almost non-existent in Ireland over the past decade. The housing boom came and has just gone, and even though climate change veered towards the centre of the international agenda during that time, we were left with a stock of new houses that are energy inefficient, poorly insulated, and often lacking in decent public transport links. The technology to significantly lower the impact of development clearly exists; the uptake, however, has been slow.

A change of direction, however, could be near. In order for environmentally sensitive development to become the rule rather than the exception, a number of factors – including incentives for developers, desire amongst homeowners, and more knowledge amongst both parties – will need to converge. The potential for this to happen has arguably never been greater.

Speaking to Construct Ireland, David Healy, a Green Party councillor for Howth and a special advisor to environment minister John Gormley, confirmed that over the coming months the department will be actively looking at introducing a scheme similar to the UK’s Code for Sustainable Homes. If a similar code is introduced on this side of the Irish Sea, it may break down one of the biggest barriers holding back demand for lower impact homes: lack of a mechanism for buyers to assess a building’s overall environmental impact. The code rates the sustainability of residential buildings by looking at factors such as energy and water efficiency, construction material and waste, pollution, green spaces and provision for cyclists. It provides an overall sustainability score for a development on a simple scale of one to six. The code, David Healy says, gives developers “an incentive for going beyond the minimum. It’s giving people both carrot and stick. We want to see the building industry enthusiastically coming along, not fighting us.”

Of course, if low impact development is to become common, more challenges than the simple lack of information amongst property buyers will need to be overcome. For a start, the construction industry will need to be convinced that such development is economically viable and cost effective. Tighter building regulations, such as those recently announced that increase the mandatory energy standard of new build by 40 per cent, are part of the solution to lowering the environmental footprint of residential buildings. But even higher standards than these – and in more areas than just energy – are needed, and simply providing a new code outlining higher environmental targets doesn’t mean that developers will try to meet them. Strong incentives are required.

In May 2006, the Sunday Times reported that a e1bn development of 2,200 houses in south Dublin would face a delay of between two and five years because pressure on the local water supply meant water could not be provided to the new residences. Those watching within the green building industry might have spotted a unique opportunity to demonstrate the potential self-sufficiency of residential sites: build the site anyway, make it self-sufficient in water and wastewater treatment, and fund the increased costs through reduced development levies.

David Healy, Special Advisor to Minister Gormley told Construct Ireland that the department is actively looking at introducing a scheme similar to the UK’s Code for Sustainable Homes

The commercial benefits of reducing environmental impacts are shown here by comparing plans for (above) BedZED with (below) BedHED (Beddington High Energy Development), a conventional development layout for the same site. Through clever use of space, and through successfully arguing for higher densities as a result of going green, BedZED became viable

How exactly could sites become self-sufficient in terms of water and wastewater treatment? Speaking to Construct Ireland, Owen Leonard of Broadstone Engineering, manufacturers of rainwater harvesting systems, claims that it is possible for a development to meet 100 per cent of its water needs on site by treating wastewater for greywater use (washing clothes, flushing toilets and gardening), and by collecting and treating rainwater to use as potable water, with a well-source as a back-up. And if a site is entirely self-sufficient in its water use, reflecting the removal of costs to the local authority of providing water to the site through a reduced development levy could provide a unique incentive for developers to go the low-impact route.

David Healy agrees. “The instances of that (reducing levies) would be with regards to the water and sewage impact. If your development is self sufficient in terms of water, it’s creating less demand for the capital investment.”

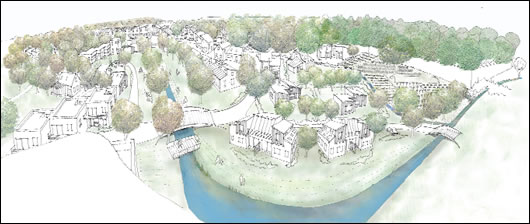

The eco village at Cloughjordan in County Tipperary as seen in these illustrations has faced many difficulties as it has tried to get itself off the ground. If such developments could be fast tracked, however, they could suddenly become a lot more common

The idea of reducing development levies for lower impact projects may be more than just hopeful Green Party policy; Andrew Hind, president of the Irish Planners’ Institute Council, is keen too. “Lower impact developments could be allowed relief on certain development taxes.” Hind stresses, however, that if such an incentive became successful in the longer term, it could impact on a local authority’s funding for key projects. Indeed, such an incentive could only be viable in the long term if reductions in development levies reflected the actual savings made by local authorities due to the site’s self-sufficiency.

Andrew Hind believes that there is considerable potential for local authorities to encourage lower impact building through their local development plans. “More local authorities could include in their development plans a provision that states that when a project is borderline on particular issues (with respect to planning permission), its environmental sensitivity could be taken into account as a balancing factor. Planning authorities have the ability to try to encourage developers to raise the bar. Developments could get extra points, essentially, for adopting an environmentally sensitive strategy. This could encourage it more.” But isn’t the environmental impact of a project already a factor that is considered in existing planning regulations? “Yes it is, but the whole energy issue in buildings is something that's come to the fore much more recently,” he acknowledges. If planning guidelines were to offer advantages to more energy efficient projects, it could offer another carrot to developers.

Hind also believes that building to high environmental standards could be a way of making it easier and more sustainable for people to build one-off housing. “In the argument about one-off houses in this country, many local authorities have a simple 'no' policy, unless you're an exceptional applicant, which usually means that you have connections to the area in question. Perhaps buildings of a particularly high environmental standard could be seen as "exceptional" too. I can see a possibility there. It might take a bit of teasing out.”

Whatever the advantages of low impact development, the simple fact remains that it usually requires more initial capital than conventional building; simply put, adding solar panels and high quality insulation to a development costs more than not doing so. This being said, however, the additional costs are usually less substantial than people might think. According to Sustainable Energy Ireland, a passivhaus that requires no energy for heating or cooling costs on average just 8 per cent more than a conventional dwelling. And while the energy efficiency of low impact properties means that these costs are inevitably recouped, the sheer pace at which developers were able to build over the past decade, coupled with our poor mandatory energy efficiency standards, meant that the goal was often to get new houses up as quickly and as cheaply as possible. High quality, efficient buildings were simply not on the agenda.

With the pace of construction slowing though, that could be about change. If developers could be convinced that low impact development was cost effective, it could become a lot more common. Reducing levies could be one way of achieving this. Increasing densities could be another.

In John Gormley, Ireland now has a Minister for the Environment who understands the economic, social and environmental benefits that low impact development can bring

The well-known BedZED (Beddington Zero Energy Development) project in London could provide an ideal model for future Irish development. BedZED is an urban estate of 99 residential units and associated workspace built on a council-owned brownfield site in the borough of Sutton, London. It is powered and heated by a combination of solar panels and a district heating system fuelled by tree waste. Rainwater collection and water-efficient appliances enable high levels of water efficiency, and car parking spaces are kept to a minimum. The development went ahead at a higher density than the council originally required when granting planning permission.

A spokesperson for BioRegional, an environmental consultancy that worked on the project, told Construct Ireland that the project was able to proceed at a higher density because there was less space for cars provided. “More properties were fitted into the space because we have good public transport and good cycling facilities. I think there were 50 per cent less car parking spaces compared to a conventional development.”

Planning permission for the site originally granted permission for 250 habitable rooms – 271 were ultimately built, plus 2,500m2 of live/work and commercial space. There are other reasons that BedZED was able to achieve a higher density. Firstly, by putting rooftop gardens on top of workspaces, the architects could reduce the amount of green space required on the ground, providing green space at a density of development that would normally only provide for balconies. And secondly, the unique integration of living and work space at BedZED, designed to reduce the need for commuting, means there is a uniquely high density of occupants.

BedZED units sold at 17-20 per cent more than conventional new homes in the area, with buyers willing to pay a premium for the sustainable design. BioRegional calculated that a developer could generate an extra £3.7m from a site like BedZED, with £2.5m being offset against the cost of constructing the extra units, leaving estimated extra revenue of £1.2m. The London Borough of Merton has now initiated a two-tier system for developers bidding for large sites under their control. At conventional standards, developers can bid at a standard density, or they can opt to bid at a higher density with projects that meet certain environmental performance criteria.

Bill Dunster, chief architect on BedZED, thinks that planning gain – offering incentives such as increased densities to developers in return for lower environmental impact - is “absolutely brilliant, it works every time.” He stresses, however, that innovative architecture – such as rooftop gardens – is needed to prevent amenity space being lost when densities are increased. “You've got to get the planners to understand that you've got to have innovative architectural solutions so you don't lose amenity space when you increase the density - conventional designs won't work." How can this be achieved? “Hire us!” he jokes wryly.

If the concept of “carbon trading for planning gain”, as Dunster calls it, really is as promising as he suggests, just why haven’t developers been using it? Dunster is equivocal: “Developers aren't prepared to be honest and discuss their finances with the local authority (in order to negotiate a planning gain). Also, estate agents try to kill off innovation because they can't predict the sale values.”

David Healy is keen on the idea of reducing car space and using it to facilitate higher densities of development and improved open spaces. “I think probably the main thing which would facilitate higher density would be reduced car parking. If you take car free developments in other countries, the reduced road space and car parking space can be shared to allow for improved open space and higher density building.” Healy cites the district of Vauban in Freiburg, Germany as a potential model for Irish development. Vauban is described as a “sustainable model district” of some 5,000 inhabitants. All homes are highly energy efficient – some are passive, requiring no input of energy whatsoever – while any energy that is required is provided by combined heat and power plants burning wood chips, solar collectors and photovoltaic cells. As with BedZED, the most interesting thing about Vauban may be the way it discourages the use of cars. Car parking spaces are only available at the edge of the development, much further from homes than tram lines. As a result, car ownership is low – only 8 per 100 people, according to David Healy – leaving considerably more space for both open areas and residential and commercial buildings.

At BedZED additional space was gained by reducing car parking to an extent, with design geared towards cyclists, with the added benefit of facilitating superior environmental performance not just for buildings, but for transport

Healy, however, isn’t in favour of providing incentives for something as simple as energy efficiency. “I don't really see how we could justify higher densities in terms of higher energy efficiency – planners are already trying to get housing to be built at a higher density.” Indeed, without an actual on-site impact, such as a reduction in car use, building at higher densities could simply be trying to squeeze more into the same amount of space, with a potential knock on impact on amenity space and quality of life. As Bill Dunster says, intelligent planning is required.

Clearly, such incentives have the potential to encourage developers to build more sustainable housing. But even if developers started to build low impact homes, do people want to buy them? In November 2005, a report commissioned and published by Sponge – a UK-based sustainable development charity - concluded that it had yet to be proven that there was a market demand for sustainable homes, and that home buyers do not fully understand what features are available to improve the sustainability of their homes. A follow-up survey conducted by Ipsus-MORI published earlier this year, however, found awareness to be much higher, with 92 per cent of respondents keen to see sustainability features included in new houses, and over half of respondents willing to pay small premiums for more homes with better environmental performance, as the success of BedZED has clearly demonstrated. Discussing the market for sustainable homes, Bill Dunster told Construct Ireland that demand has always been very high for the “green” projects he has worked on.

Attitudes appear to be changing, and the introduction of something akin to the Code for Sustainable Homes in Ireland – combined with the shifting of power from developer to buyer resulting from the building slowdown - could provide the foundation homebuyers need in order to make informed decisions, and demand higher standards.

However, does what appears to be an overdependence in Ireland on construction for our economic prosperity mean that sustainable housing is forever resigned to being pushed aside by “conventional” construction due to the pressure to keep building in order to keep the economy ticking? David Healy doesn’t think so: “It could be the case if these were seen as enormously difficult requirements. But they only appear to be big changes because we've built to very low standards. I don't think it necessarily has any impact. It's a great regret that these standards weren't introduced at the start of the building boom ten years ago.”

Speaking in last month’s issue of Construct Ireland, John Gormley spoke of his desire to see eco villages become commonplace in Ireland. “We talk about fast-tracking infrastructural projects, to me fast-tracking the eco-village concept would be the best way of doing it”, he said. The eco village at Cloughjordan in County Tipperary has faced many difficulties as it has tried to get itself off the ground. If such developments could be fast tracked, however, they could suddenly become a lot more common.

All of the factors required to make low impact development the norm appear to be converging. The technology is obviously available, power is shifting to more informed, empowered buyers and a market demand is beginning to emerge. Political will appears to exist, as do simple, clear ideas to entice and encourage developers. It would be a serious shame if these opportunities were not now capitalised upon.

- Articles

- Design Approaches

- Green Gains

- housing boom

- David Healy

- John Gormley

- rainwater harvesting

- BedZED

- photovoltaic cells

Related items

-

Steeply sustainable - Low carbon passive design wonder on impossible Cork site

Steeply sustainable - Low carbon passive design wonder on impossible Cork site -

Focus on whole build systems, not products - NBT

Focus on whole build systems, not products - NBT -

International - Issue 29

International - Issue 29 -

Passive Wexford bungalow with a hint of the exotic

Passive Wexford bungalow with a hint of the exotic -

The House of Tomorrow, 1933

The House of Tomorrow, 1933 -

1948: The Dover Sun House

1948: The Dover Sun House -

The dazzling Dalkey home with a hidden agenda

The dazzling Dalkey home with a hidden agenda -

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather -

A1 passive house overcomes tight Cork City site

A1 passive house overcomes tight Cork City site -

Norfolk straw-bale cottage aims for passive

Norfolk straw-bale cottage aims for passive -

Time to move beyond the architecture of the oil age

Time to move beyond the architecture of the oil age -

West Cork passive house raises design bar

West Cork passive house raises design bar