- Design Approaches

- Posted

Southern comfort

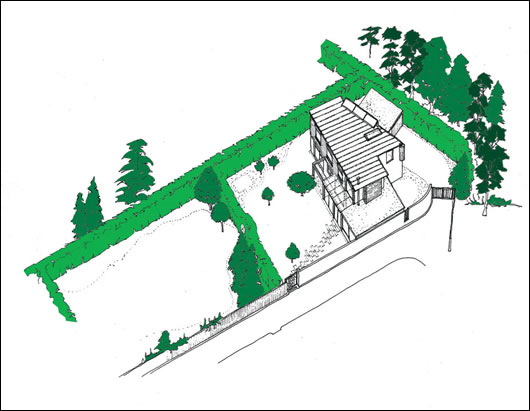

Sustainable building at its best is about much more than just energy and carbon emissions, and involves considering location, form, orientation and the use of healthy, environmentally friendly materials. Mike Haslam of trail-blazing ecological architects Solearth describes a family home which scores highly on every frontThis house – the first suburban family house designed by Solearth – was completed early last year at the rear of a long garden space to an existing house in south County Dublin. It consists of a two-storey, three-bed, 190sqm house including an attached sunroom space and garden.

The house is part of a larger scale project that placed a communal driveway between two houses on the street, developed the back gardens of both and included works to both the existing houses. The position of the two new houses can be considered as small-scale back-land development, which is positively referred to in the Dun Laoghaire Rathdown Draft Development Plan of 2003. This sought to maintain the population density of the county and increase it particularly in those areas in proximity to good public transport routes including the Luas. Where we think this project differs from many in this process of densification is that it is respectful to the existing character and qualities of the neighbourhood –speaking about increasing density without talking about quality of life is very unsound.

The new house importantly maintains most of the existing hedgerows and trees, including apple trees, on the site. Living in suburbia must be about the connection both to the city and to nature and we sought to maintain this relationship. The scale of the new house is such that it makes no attempt to compete with the existing grander scale of the street frontage but rather sits more modestly as a garden pavilion typology. The house positioning takes account of relevant boundary distances and the need to maximise both the south facing garden and also solar ingress into the house. The form of the house is indeed dictated by these conditions and ties itself to the garden wall with the living room thus cementing its relationship with the access route to the property.

(above left) The north view of the house, the exposed glulam beam above the front door acknowledging the building’s timber anatomy; (below right) wild flowers in the garden reinforce the sense of leafy suburban setting

Looking out onto the garden from the sunroom, with slate floor for thermal mass and heat absorption, and solar shading on the roof to prevent overheating

The design of the house reflects several important aspects: it is both a passive and active solar-designed house. Its orientation to the south and the openings towards the south are important and abetted by the siting. The ground floor sunspace with darkened slate floor connects dining, living and hall and through the hall stair to the upper floor serving to circulate sun-warmed air through the house. An evacuated tube solar array sits atop the roof, orientated correctly to optimise its year round usage and feeds heat back to the buffer tank in the utility room. The plan layout of the house also follows passive solar design principles, placing the living/sleeping spaces to the south and service spaces to the north, positioning them successfully in the more awkward triangular geometry on this side of the house.

Opaque glass was chosen in the bathroom partly to filter light. Note the laundry chute

The copper roof form is as minimal as necessary in order to accommodate two storeys and at the same time reduce impact on the surroundings. The use of copper facilitates the low pitch of the roof, which was an important part of the scale relationship to surrounding houses and trees, as well as providing a durable attractive finish that will age gracefully. The high-embodied energy of this material makes it unattractive from an environmental point of view – we took the position that use of such material must only be in areas where it has to perform at a particularly high level and other options such as tiles – due to the pitch of the roof – were not available to us. At an earlier stage the roof was also to gather rainwater for collection and reuse in flushing toilets and for the garden, however this was dropped from the agenda. Problems encountered on other projects with placing water tanks into ground with a high water table make this solution, in our view, unviable for most single houses.

The building is predominantly rendered with a timber screen at first floor level to the south. This reflects the suburban palette of materials in the area and the first floor timber screen also acknowledges the woodland cover to the north of the site. Originally designed as a Poroton construction – a material much used and enjoyed by this office for its simplicity and dependability – with timber frame supporting those areas clad in timber. We changed at pre tender stage to closed panel timber frame throughout: this allowed us to increase our levels of insulation without losing space internally and also allowed us to look at prefabrication to speed up the site process (a planning appeal had set the programme back by some 6 months).

We had worked with open panel frame and stick build construction on a number of projects previously – the Daintree building in Dublin and the Tobin House in Cork – allowing us to build up a well insulated breathable wall construction and particularly useful where building geometries were complex such as in the Daintree building. On this project with simple timber geometries, we decided to investigate closed panel timber frame, again with an eye on programme and also on a turnkey level of quality. Both the very engaged client (who visited Austria to check out factories) and ourselves spent not an inconsiderable time researching the various systems on offer. The criteria for us hinged around the quality of the product; the companies’ track record in Ireland, which also meant having a manufacturing base here; the ability to work closely with our design, bring added quality to it and, of course, the cost. These aspects narrowed the field down considerably and it was the Obweger system – represented in Ireland at that time by Josef Steiner at Okohaus – that we chose.

Obweger worked with the main contractor on the house with the contractor’s appointed electrical and mechanical subcontractors. An enabling works programme facilitated the communal drive way and laid the concrete base to the house, off which the timber frame was constructed. We bought into the Obweger constructional system, which led to only minor changes in overall design. It did however change certain aspects of detail design. Our lime render on heraklith cladding system was replaced by the simpler, transportable but less environmentally friendly silicon resin render, which has however proved very durable. Our Donegal sourced western red cedar cladding was replaced by Austrian larch, though again it has proved itself both a durable and attractive finish. Our initial hope that the frame would be constructed in Athy utilising a percentage of home-sourced timber was not realised, as the plant there was not capable of the closed panel construction. The building was largely then manufactured in Austria and thus our transport energy costs increased with both truck and ferry. The team that erected the house were also Austrian, on their tour of duty in Ireland and highly efficient at that task, though the subcontractors were Irish based.

The entrance hall looking south towards the sun room (behind the timber stairs) with the living room to the left

A sketch of the house and garden, where many of the existing hedgerows and trees were maintained

The closed panel wall system consists of gypsum fibreboard internally on OSB - utilised for racking strength and with taped joints for air-tightness; a 200mm depth of stud work filled with flax insulation and then 16mm of DWD wood fibre board breathable insulation over the stud work. A breather membrane is fixed to the outside of the wall build-up followed by timber battens and either larch cladding or Sto Verotec panel with silicon resin render. The roof construction has a similar build up, but places a 30mm insulated service cavity on the inside face of the taped OSB board – so that wiring does not puncture the airtight skin – and is finished externally with a ventilated copper roof. The first floor construction is insulated thermally and acoustically, and the ground floor is built up off the slab with 100mm of rigid insulation supporting a screed, which incorporates under floor heating coils. External windows and doors were provided by the Austrian firm Katzbeck using double glazed low-e and argon-filled units, framed in multi laminate larch for dimensional stability. Finishing was crisp throughout and included European ply engineered oak boards over the heated screed, marmoleum in the kitchen and natural paint finishes.

From a servicing point of view the house relies heavily on its well-insulated airtight construction and passive solar design to minimise heat loss and maximise incidental gain from occupancy. The back up heating system used is a condensing gas boiler – not our first choice environmentally, however, on the occasion of its winter malfunction during defects period it was not unduly missed thanks to the nature of the building envelope.

The building performs well from a constructional and energy perspective and we intend to go back and measure actual energy performance as we move into this time of energy ratings. Importantly too, the house functions very much as a home and a return visit is a welcome reminder of how people engage positively with buildings and how buildings can positively modify their external environment.

The kitchen table, with the hand-made kitchen by Eamon O’Sullivan and sun space in the background

Selected project details

Architects: Mike Haslam, Solearth Ecological Architecture

Structural engineer: Malone O’Regan

Quantity surveyors: DL Martin and Partners

Build system: Obweger

Enabling works: Peter Mant Ltd.

Windows and external doors: Katzbeck

Kitchen: Don and Eamonn O’Sullivan

Stairs: Die Holzer Stiege

- Articles

- Design Approaches

- Southern comfort

- timber frame

- Solearth

- passive house

- Solar design

- Obweger

Related items

-

Peaky blinder

Peaky blinder -

Up to 11

Up to 11 -

It's a lovely house to live in now

It's a lovely house to live in now -

We Build Eco flat pack timber frame partnership gathers pace

We Build Eco flat pack timber frame partnership gathers pace -

Big picture - New Zealand rural passive home

Big picture - New Zealand rural passive home -

Podcast: what we've learned from 20 years in green building mags

Podcast: what we've learned from 20 years in green building mags -

Mass timber masterwork

Mass timber masterwork -

AECB conference to showcase timber innovation

AECB conference to showcase timber innovation -

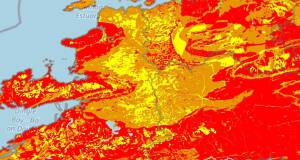

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal -

Passive house 30 years on: qualified success or brilliant failure?

Passive house 30 years on: qualified success or brilliant failure? -

Heart of oak

Heart of oak -

Welsh social housing to embrace passive house, timber & life cycle assessment

Welsh social housing to embrace passive house, timber & life cycle assessment