- Design Approaches

- Posted

Eco Lodgings

The hospitality industry is not thought of as being particularly green—huge heating, air conditioning and lighting needs make for massive energy consumption and razor thin margins mean that expensive technologies have not been a top priority for most. As energy prices increase, this is starting to change. Construct Ireland’s Jason Walsh visited the Brooklodge in Macreddin, County Wicklow, to find out about how one hotel has found rising fossil fuel costs the perfect reason to invest in a sustainable future.

I didn't quite know what to expect at Macreddin—a bustling village or town, or another one of those Irish non-places of which Gertrude Stein might have said, "There's no there, there." The landscape is beautiful to be sure, but that's Wicklow for you. There are parts of Wicklow so ruggedly picturesque that it's possible to convince oneself, erroneously, that this must be the land in which Edmund Burke became enraptured by the sublime.

Still, Macreddin itself was beside the point. The objective was to visit the Brooklodge Hotel to find out how the recently installed environmental sustainability measures were performing, and why they were installed in the first place.

Country house hotels aren't for everyone. I, for example, am torn between the twin poles of hyper-urbanism and the ultra-rural. As a result, country house hotels don't even appear on my radar.

However, the Brooklodge is not a non-place. Set in large grounds complete with golf course, spa and a microbrewery, to 40 bed hotel is, if not Brobdingnagian, at least very spacious.

Sitting in the lobby, waiting on the hotel's manager and co-proprietor, Evan Doyle, to arrive it becomes clear very quickly that this is a popular destination. I arrived at 11AM on a Monday morning, right in the middle of the checkout process for the weekend's guests. Sitting within earshot of reception, I heard superlative upon superlative bestowed upon the hotel's staff—unprompted. From the spa to the restaurants to the general comfort level, everything was, it seems, a pleasure.

Clearly already a hit with guests, in an era of increasing environmental consciousness, does the hotel have a further ace hidden in its sleeve: sustainability?

The hotel's restaurant, the Strawberry Tree was—and is—Ireland's only licenced organic restaurant. In fact, when the Green Party was searching for a location suitable for its 2006 'think in', it lit upon the Brooklodge, choosing it because of its organic restaurant and "other eco-friendly measures." Those "eco-friendly measures" include a move to renewable energy sources.

Engineering solutions For businesspeople like Doyle, the key reason to switch to renewable energy sources is financial: the price of oil and gas has exploded in recent years, making renewables, once a fringe interest in Ireland, a solid business proposition.

Evan Doyle himself explains: "The big push was energy costs. The hotel was [originally] built with traditional gas and electricity supplies."

Aside from spiraling energy costs, the Brooklodge took the opportunity to go green when the decision was taken to expand the hotel in 2005. Two new blocks were designed and built. The first, a conference centre and set of bedrooms opened in the summer of 2006 while the second, a function room, kitchen and further guest bedrooms, is due to open in January 2007.

"When we built the conference centre, we discovered there was an underground spring and I'd heard that, on the continent, they had been used for geothermal heating," says Doyle.

Used in conjunction with a biomass burner, the hotel has now moved entirely to environmentally conscious energy sources, retaining the existing gas supply only as a failsafe backup system: "I suppose we've spent €350 – 400,000 on renewable energy sources [and systems]. It has to be looked at from a business perspective."

And it has been: as a result of switching to renewables, the hotel's heating bill has been slashed, and further savings are on the cards: "Since we pushed the button the price of energy has sky-rocketed," says Doyle.

Nevertheless, despite the understandable interest in the bottom line, it would not be true to say that Doyle doesn't take a keen interest in environmental issues. In fact, he has invested €42,000 in a composter for kitchen waste and all of the hotel's paper waste is recycled.

Joe Rooney of RN Murphy, consulting engineers who worked on the upgrade, explains that Doyle's interest in sustainability made his company's job much easier: "One of the things that was very useful from the consultants' point of view [is that] the client was very proactive in wanting a green hotel with a very efficient use of energy. He helped us lead the way."

According to Rooney, with the two new buildings in mind, continuing with the existing heating system would simply not have been a rational choice: "The hotel was originally designed with two traditional Calor Kosangas LPG [liquid petroleum gas] boilers—it would not have been efficient."

The systems that were chosen, geothermal and biomass, reflect a clear understanding of both the hotel's consumption needs and the engineering needed to complete the work: "The last extension that has been completed is a standalone building with conference rooms on the ground floor and bedrooms above. Because the building lies in an area with a high water table, we were able to fit the [geothermal] loop within the footprint of the building.

"The new building, a combination of bedrooms and a function room, will use geothermal and wood chip," he says.

Blowing hot and cold The geothermal system was sourced from DC Compute Air. David Roome from the company says the energy cost savings with such systems are significant: "In terms of savings, you should expect, with geothermal, to see 70 per cent savings against oil," he claims.

However, Roome cautions against ill-conceived schemes and argues that successful installation requires meticulous planning: "How it's designed is the big issue. The heat pump is only the car's engine, so to speak.

"For instance, if you took an ordinary underfloor heating system, your pumping power could be twenty per cent. You could have 0.6 or 0.7 of a kilowatt going in on top of the [other] energy use," he says.

Despite this, Roome remains a champion of the technology: "A heat pump is about 450 per cent efficient where a boiler is about 70 per cent efficient.

"What we've done [in the Brooklodge] is, the actual geothermal loops are under the buildings' footprints. We've effectively created a pond from the springs.

"Under the bedroom block, there is about 2,000 metres of piping [twenty 200 metre-long loops] with a capacity of 57–60 kilowatts. The piping is buried in the gravel to allow the water to flow over it. The other building has 16,000 metres of piping with a capacity of 300 kilowatts.

"They're heating and cooling. During cooling, we discharge heat under the building and, in the heating mode, we take it up.

"Only the second building is backed-up by the wood chip boiler because the function centre is a major draw and the building still requires a lot of hot water," says Roome.

In this building geothermal energy supplies the air conditioning and cooling and a water-to-water heat pump provides heat for the domestic water and underfloor heating as well as heating the swimming pool. The wood chip burner supplies the kitchen and provides a failsafe backup.

"In the bedroom [and conferece] block it's all done by the heat pump," says Roome. "They have 1,200 litres of hot water and underfloor heating."

The same reversible heat pump pre-heats the water to 40 degrees Celsius, which is then topped-up by night-rate electricity.

Tests are currently underway to investigate the system's performance.

Burning issues When it came to choosing a renewable energy source for the existing hotel block, geothermal was considered out of the question, requiring as it would, major feats of engineering and the closure of the hotel for the duration. As a result, a decision was taken to retrofit a biomass energy system.

Of course, the hotel could simply have decided to stick with the tried and tested liquid petroleum gas system that had been up and running since 1999, leaving the green energy only in the two new blocks. However, such half measures were not given serious thought and Doyle lit upon biomass.

The biomass chosen for the Brooklodge was a wood chip burner: "With the price of gas going where it was plus the possibility of carbon taxes, I began to look at wood chip to heat the hotel," says Doyle.

Simon Dick from Clearpower, the system's supplier, explains how things came about: "We didn't do a formal presentation. Evan's pretty innovative and we moved quickly—we did a feasibility study and then won the project."

A 200 kilowatt wood chip burner system was chosen to provide the baseload heat for the hotel: "We calculated a 200 kilowatt boiler based on the last year's LPG fuel usage. We sized the boiler so that it was working at 100 per cent efficiency."

Dick explains that running a wood burner based boiler at or near 100 per cent efficiency is the norm: "You don't want to be putting in a boiler that's twice as powerful as required," he says. "With wood you want to aim for maximum efficiency. We aimed for 200 KW, knowing the LPG could kick in for peak loads if required.

"The difference between wood and LPG or oil is that, with wood, the capital cost is high but the fuel is cheap," he says.

Indeed, and given that the last few years have seen continually increasing fossil fuel costs, carbon neutral biomass fuels such as wood chip and wood pellets will be even cheaper in comparison with traditional fuels, but what about their performance?

Dick explains the calculations: "The consumption of LPG was 215,000 litres over the previous year, which equates to 1.56 million kilowatt hours per annum. The heat requirement, we estimated, is 1.326 kilowatt hours per annum. [With LPG] You have a conversion efficiency of around 85 per cent.

"This added up to about €78,000 per year. The total [capital] cost for the wood chip boiler was about €70,000. The running costs of €78,000 per year with LPG are based on fuel costs of just over 5c per kilowatt hour. We deliver the [wood chip] fuel at a little over 2c per kilowatt hour. On that basis alone, they would be saving about €40,000 per year on their fuel bill," he says.

Regarding the environmental impact, Dick points out that every litre of LPG emits carbon and that the hotel was using 215,000 litres per year. Today, those emissions no longer happen. "Wood is carbon neutral," he says.

He also points to other positive effects of switching over to biomass: "There are a lot of benefits: we've created a few more jobs in rural areas, creating and delivering the fuel; we've created a market for forest thinnings, which has to be done anyway. Obviously there are the CO2 benefits—we, Ireland Inc., are going to be fined this year."

Dick thinks that although things continue to improve in Ireland, the country is still too reliant on fossil fuels—and that's without even considering the aforementioned carbon emissions: "We're using fossil fuels like you'd lash in the pints at a free bar. We don't seem to realise we're an island and [therefore] at the end of the supply chain. Security of supply is an issue."

The recent problems surrounding the Gazprom gas supply in Russia and Ukraine indicates just how sensitive the supply of fossil fuels is to geopolitical issues. President of Russia, Vladimir Putin, last year threatened to completely cut supplies to Western Europe and, indeed, dramatically reduced the supply to Ukraine during a diplomatic spat with the former Soviet satellite state.

Nevertheless, there has been some discussion over whether wood chip is a suitably efficient alternative energy source, particularly with relation to moisture levels in the timber. Dick says such fears are unfounded: "We have moisture metres and we dry the chip using air vents.

"It's the same as grain," he says. "Grain can be supplied at plus or minus one percent [moisture]. With wood chip, it's exactly the same technology.

"I think there's a confusion in the market about wood chip versus wood pellets. Pellet fuel is processed—that's another step, in the same way that you have light and heavy oil," says Dick. Which is not to say that Clearpower is against pellets per se. Dick indicates that his company recently installed a pellet system for a client where storage space was a major issue.

According to Dick, one benefit of a wood chip system is that it can also utilise other wood-based fuels, including wood pellets: "Chip boilers are produced to use both. Pellets were really developed for the domestic market. I don't think the efficiencies are any better, but [with wood pellets] you do have an extra cost. [The point is to] Design up front to take both—play the market. If you don't get the quality of supply of chip, you can always switch to pellets."

The future's bright Ultimately, the Brooklodge's move to renewable energy sources is still under test. Doyle will be using metres for both the wood chip burner and geothermal system in order to get a clear price per watt energy figure.

The Brooklodge may be an early adopter of renewable energy in the hospitality industry but similar moves by its competitors seem logical: "There's more and more talk of carbon taxes—they seem inevitable," says Doyle.

Moreover, Doyle's experience makes a strong economic argument for investing in progressive energy sources without even thinking about the possibility of avoiding a supplementary tax burden: "Anecdotally, without a shadow of a doubt it's working," he says. "It's gone from a projected five year return on investment to under three years." That's progress.

Selected project team members and suppliers

Client: Brooklodge and Wells Spa Consulting engineer: RN Murphy Heat pump: DC Compute Air Wood chip boiler: Clearpower

Related items

-

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries -

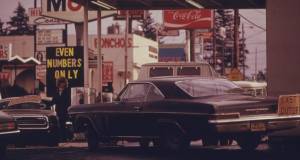

The first oil crisis

The first oil crisis -

Steeply sustainable - Low carbon passive design wonder on impossible Cork site

Steeply sustainable - Low carbon passive design wonder on impossible Cork site -

Focus on whole build systems, not products - NBT

Focus on whole build systems, not products - NBT -

International - Issue 29

International - Issue 29 -

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March -

Passive Wexford bungalow with a hint of the exotic

Passive Wexford bungalow with a hint of the exotic -

The House of Tomorrow, 1933

The House of Tomorrow, 1933 -

1948: The Dover Sun House

1948: The Dover Sun House -

The dazzling Dalkey home with a hidden agenda

The dazzling Dalkey home with a hidden agenda -

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather -

A1 passive house overcomes tight Cork City site

A1 passive house overcomes tight Cork City site