- Design Approaches

- Posted

Bio Logic

Stricter air-tightness standards might be helping to reduce energy use in new build, but is it leading to higher indoor concentrations of chemical and biological toxins? Lenny Antonelli investigates an emerging approach to building that is combining attention to environmental impact with consideration for the potential health effects of modern building materials and practices.The push for higher air-tightness standards might be improving the energy performance of buildings, but what affect is it having on the health of occupants? Mike Haslam of Solearth architects is concerned: “The focus is very much on energy with the ‘build tight, ventilate right’ message,” he says, “but there's a real danger that the ‘ventilate right’ part isn't getting through. We perhaps got away with high concentrations of internal toxins and volatile organic compounds before because our buildings were so leaky, but that's not the case any more. If we're not aware what we're putting into buildings, there's a real health danger.”

As well as being an architect, Haslam is also qualified in building biology, an emerging discipline that examines the ways in which buildings affect human health. Principle concerns include indoor air quality and electromagnetic radiation. “Building biology takes a whole view of the connections between the built and unbuilt environment, and human biology”, says Uwe Yarwood, another architect-cum-building biologist working in Ireland. The discipline treats buildings as a ‘third skin’ that is just as important to human health as our skin or clothing.

Interest in the relationship between buildings and human health is not new.

As far back as 1982, the World Health Organisation recognised sick building syndrome, a combination of symptoms – including fatigue, nausea and headache – linked to the amount of time spent in a building. While specific causes of sick building syndrome haven’t been pinpointed, poor ventilation and associated air-borne chemical and biological contamination are all believed to play a role.

Fortunately, the way buildings are designed and built can go a long way towards making them healthier, and this is where building biologists come in. The discipline is based on 25 founding principles that act as guidelines for everything from site selection and choice of building materials down to the placing of electrical sockets.

Indoor air pollution is perhaps the concern for building biologists, and mould is one of the primary causes of poor indoor air quality, particularly in damp and rainy Ireland. Microscopic spores released by common mould species have been linked with symptoms such as eye and skin irritation, wheezing and fever. A smart choice of building materials, however, can help to prevent the problem.

“If we want to avoid mould, we can choose breathable building materials such as clay and lime. Lime has antiseptic properties too, so helps to prevent mould growth,” Uwe Yarwood says. Mike Haslam elaborates on breathable building materials: “Timber and some timber-based boards and gypsum plasters have a high degree of breathability. Poroton has a certain degree of breathability too.”

Building biologists tend to prefer natural insulation products such as sheep wool (above) and wood fibre (below) because of its health benefits, not only for consumers, but for the builder working with the material

When it comes to treating pre-existing mould problems, building biologist Bodo Bodewigs of Sligo-based Healthbuild stresses that it’s not just a matter of removal, but examining the whole design of a building. “You have to look at wider issues of heating, condensation problems and insulation and provide qualified advice. There’s more to it than just advising on mould removal,” he says.

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are another concern. They are commonly found in synthetic glues, varnishes, paints, finishes and certain building materials. They can evaporate rapidly and pose potential health threats if inhaled in high concentrations. Exposure has been linked to a variety of symptoms, including headache, nausea and dizziness, and at high concentrations, liver and kidney damage.

Formaldehyde is a principle offender amongst VOCs. It is used in a variety of wood products, including particleboard, fibreboard and plywood wall panels (though formaldehyde free varieties of these products are available) and some insulation materials, such as urea-formaldehyde foam. Exposure to high concentrations of formaldehydes can cause nausea, coughing, skin rashes and flu-like symptoms.

“An awful lot of modern building materials are emitting toxic fumes,” says Dr. Phillip Michael of the Irish Doctors’ Environmental Association, citing PVC a noteworthy example. PVC building materials commonly contain lead, cadmium and phthalate plasticisers, which can flake off or outgas and increase the risk of a variety of health problems. Impermeable vinyl wall coverings can also facilitate the growth of mould. “A lot of glues and paints are emitting toxic fumes months after they’ve been placed,” Dr Michael adds. “We’d recommend using natural materials as much as possible.”

While indoor VOCs and mould posed less of a problem in the past, stricter air tightness targets are changing that. “In an attempt to reduce heat loss people are sealing their houses, but that’s not a good idea either, says Dr Phillip Michael. “Walls need to be able to breathe.” According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, stricter air tightness standards since the 1973 oil crisis have played a role in the increasing prevalence of sick building syndrome.

Good ventilation is obviously crucial for building biologists, with designed passive systems being preferred. “You don’t really want to put energy into something that can work passively,” Mike Haslam says, citing the passive heat exchange system employed at the renowned BedZed low energy housing development in London as an innovative example. The system provides the dwellings with sufficient ventilation without letting cool air in, and with no energy expended. The average home doesn’t need such an innovative system of course – simple window trickle vents were recommended by a number of the building biologists Construct Ireland spoke to.

Providing a healthy indoor environment is about more than just ventilation of course. “Using natural materials is a fundamental premise of building biology,” Mike Haslam says. “They tend to be benign, or hydroscopic, or have low embodied energy. They fulfill most of the criteria in relation to health.” Haslam prefers marmoleum flooring – made with linseed oil, wood flour, rosin, jute and limestone – to vinyl products. “We also try to minimise using glues in the building,” he adds. “If we're putting down a floor, we'll try to use secret nail fixings rather than gluing it. It’s for health reasons and about the ease of reuse.” If glues must be used, Haslam says he’ll choose low VOC products. “The same would go for paint finishes,” he adds.

Ivonne Rissman, the building biologist with Dublin-based Continental Homes, who have been building prefabricated timber-frame houses in Ireland for the past five years, also stresses the importance of natural materials. “Our use of breathable, ecological and non-toxic materials is paramount to our system,” she says. A formaldehyde-free wood fibre insulating board is paramount to the company’s building system, and as you might expect, their insulation materials of choice include natural products such as sheep’s wool, cellulose fibre and hemp-based materials.

Mike Haslam explains why building biologists prefer natural insulation products: “The building biologist is concerned with the health of the occupant, but even if the occupants will never come in contact with a certain building material, the architect also has a responsibility to the builders and installers who work with those materials. There's also a responsibility health-wise towards those who will be taking things down and disposing of them in the future.” This means avoiding potentially irritating insulation products, such as glass wool.

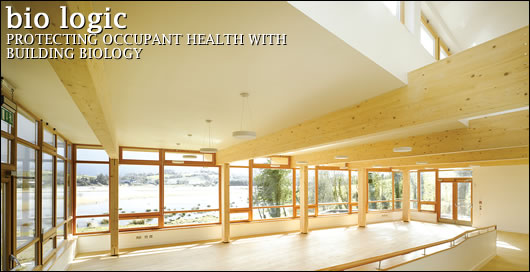

The atrium of Leech-Gaia Ecotecture’s Navan Credit Union, a building where great attention to detail was paid in terms of specifying healthy, low embodied energy materials

This writer can vouch for the improvement in indoor air quality that results from applying the principles of building biology, having recently spent four days working in a cottage renovated with hemp-lime walls, a breathable roofing system and natural paints. The indoor air was noticeably fresher, and the familiar urge to step outside every few hours for fresh air was non-existent. Despite this, the cottage was warm and well insulated, and there were no noticeable draughts.

Minimising indoor exposure to electromagnetic (EM) radiation is another aim for building biologists. All household wiring emits an electrical field, and excessive exposure to such fields has been linked to a variety of acute health problems, including depression and some cancers. However, the World Health Organisation says that evidence for this link is weak.

Taking a precautionary approach, building biologists advise against putting occupants in close contact with electrical fittings - near beds for example. “In general wiring should be kept to a minimum and kept away from your sleeping position,” Dr Phillip Michael says. Mike Haslam actively applies this principle: “In the design of the house I’d be trying to minimise electrical circuits in bedrooms and restrooms. At work we’re often in an electrically stressed environment. Our places of rest should not be surrounded by electrical equipment. I would not take the risk, we should allow our bodies to have some form of rejuvenation.” There are a variety of products available on the market to minimise fields from domestic wiring.

Building biologists are also concerned about radon emitted from certain building materials. “Some concrete is coming from radon-rich geology,” Paul Leech of Gaia Ecotecture warns. Leech says that he “seriously got into building biology about 20 years ago,” and that he “actively applies the principles from first design down to the placing of electrical sockets.”

The building’s six storey structure is almost entirely timber

Granite and other building materials also emit radon, though the levels vary depending on their geological origin. However, the US Environmental Protection Agency advises that “building materials rarely cause radon problems by themselves.”

Interest in building biology is growing. Just as the sustainable building in Ireland has been inspired by earlier developments in Germany, so has the burgeoning building biology sector. Mike Haslam outlines the origins of the discipline: “The Institute of Building Biology and Ecology was founded on the basis of a court case against the timber industry in Germany back in the seventies regarding the health affect of preservative toxins added to timber.”

Even in its homeland though, building biology is still relatively new: “It’s still quite a new profession, so it’s new for the German people,” Ivonne Rissman says. “I was the first building biologist my family had ever heard of.” Rissman estimates that there are about 6,000 building biologists working in Germany, but probably less than 10 in Ireland. “I still meet German people in Ireland who haven’t heard of building biology though,” she adds.

How do Rissman’s customers in Ireland respond to the idea? “It depends how far the customer wants to take it,” she says. “Most of them are very open to the idea. Of course some aren’t interested, but most want to know more about building biology. At present, about 30 per cent of our buildings are constructed to a totally risk-free standard.”

“If we’re really lucky we get to be involved from the early stages of planning and designing a building,” Uwe Yarwood says. That luxury isn’t always there, however, and building biologists often deal with problems in pre-existing buildings. Indeed, as well as consulting on new building projects, many practitioners advise on the remediation of existing buildings. “We can measure things like toxin levels, electromagnetic fields, spore and mould quantity, and moisture levels in building materials or in the building structure,” Uwe Yarwood explains. “We also might consult someone who is looking to buy a property,” he adds. “We can assess the house and suggest improvements, or in some cases we might even warn against buying it.”

A worker in Continental Homes’ factory building timber sections with nails and thereby reducing the use of glues

Building biology is quickly evolving, according to Ivonne Rissman. “Our organisation (the German Building Biologist Network) is constantly introducing new methods and ideologies to inform architects, engineers and builders,” she says. She feels strongly that legislation should be introduced to regulate potentially health-threatening building materials and practices. “The lack of legislative enforcement is an issue,” she says.

“Even for healthy people, there are advantages to building biology,” Uwe Yarwood stresses. “It helps to keep them healthy. It means a better quality of life, and knowing people have helped themselves, their family, future generations, and the environment.”

- Articles

- Design Approaches

- Bio logic

- airtightness

- Solearth

- sick building syndrome

- Volatile organic compounds

- German Building Biologist Network

Related items

-

Air tightness training course to launch in Carlow this March

-

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house -

Airtight delight

Airtight delight -

Partel’s airtight membranes now certified for passive house construction

Partel’s airtight membranes now certified for passive house construction -

Mass timber masterwork

Mass timber masterwork -

Partel obtains EPDs for airtight membranes

Partel obtains EPDs for airtight membranes -

Manhattan modular apartments feature Wraptite membrane

Manhattan modular apartments feature Wraptite membrane -

Partel’s Izoperm Plus achieves passive house ‘A’ cert

Partel’s Izoperm Plus achieves passive house ‘A’ cert -

Superb airtightness result for Manchester ICF house

Superb airtightness result for Manchester ICF house -

Liquid membranes transforming airtightness work — Blowerproof UK

Liquid membranes transforming airtightness work — Blowerproof UK -

AECB launches new retrofit standard

AECB launches new retrofit standard -

Pro clima launch spray applicator for airtight paints

Pro clima launch spray applicator for airtight paints