- New build

- Posted

From Nero to zero

The historic Roman city of York is embarking on an ambitious programme to redefine council housing for the 21st century, building 450 mixed-tenure passive houses across eight sites in the city, and unashamedly prioritising walking and cycling, and shared outdoor green spaces, over cars. It may seem too good to be true, but a cityscape whose architecture still so manifestly displays its extraordinary history is now pointing to the future of urban design.

Click here for project specs and suppliers

Scheme: 450 passive houses across eight sites in York; mixed tenure

Method: Timber frame

Location: York, England

Standard: Passive house classic targeted

City of York Council has embarked on arguably the most ambitious passive house scheme so far conceived by any local government in the UK.

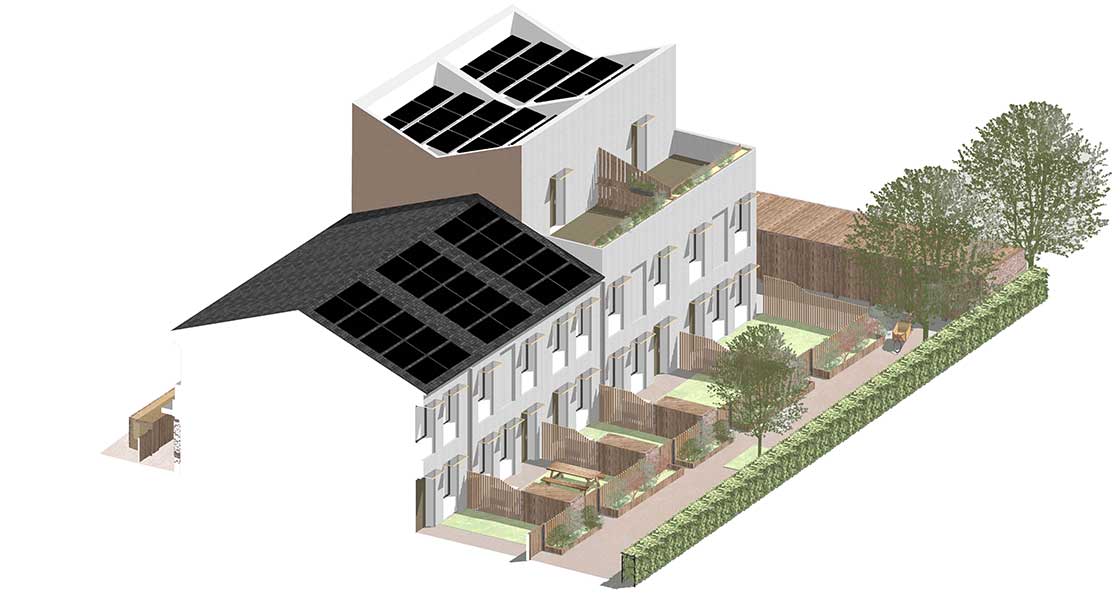

The council is building 600 energy efficient homes across about eight sites near the centre of the city, and 450 of them will not only be passive houses, but also net zero carbon for operational energy. What’s more, York have hired Stirling Prize winning architects Mikhail Riches to design the schemes.

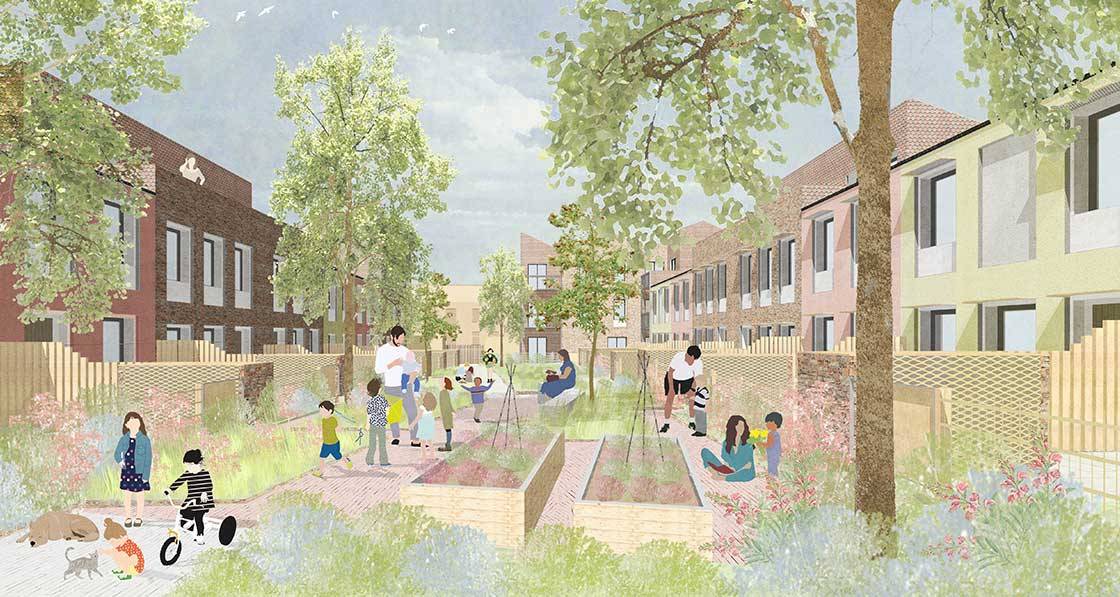

These radical developments are nothing less than a re-imagining of how society can best function in the 21st century. Everything has been done to make the mixed-tenure developments accessible to all social classes and age groups. Car use is discouraged; every home has a bike shed and private open space; green communal areas run between the homes and around the sides.

We are passionate about creating communities with mixed demographics.

The schemes have taken inspiration from Joseph Rowntree, the York chocolatier who built the model village of New Earswick on the outskirts of York at the start of the 20th century. In New Earswick, the arts and crafts houses lie along streets lined with grass verges. Two fruit trees have been planted in every garden and the homes are flooded with light. In an egalitarian manner, there are houses for both workers and managers.

But whereas Rowntree was concerned with presenting an alternative to the city’s slums and deprivation, an effort has been made to adapt his ideas for the modern age, says Michael Jones, York’s head of housing delivery and asset management.

“Joseph Rowntree was a great inspiration. We directly borrowed from his ideas, such as planting trees for every home, designing homes so that they are filled with natural light and having front doors that open onto green spaces rather than roads. Like Rowntree, we have made the developments as inclusive as possible so people can live there regardless of job and income. Our goal is to tackle modern-day social ills, which are very different to what they were in 1902,” he says.

One reason behind Jones’ desire to develop passive houses for York was his experience in charge of an ambitious 500-home development for the Joseph Rowntree Trust in 2016-2017. Derwenthorpe was also a mixed-tenure scheme, with open spaces, self-sustaining communities and low carbon goals. But the homes were not passive houses and sometimes didn’t live up to their ambitions in terms of energy performance.

The schemes have taken inspiration from Joseph Rowntree, the York chocolatier who built the model village of New Earswick.

“It too was very ambitious. We thought about health, wellbeing and communities that support each other, reducing reliance on the state and private car ownership. But there were performance gaps, some of the homes were not as warm as expected, or residents felt draughts. What drew me to passive house is you get what you pay for. The testing and certification process provides a lot of confidence for the client team.”

But the council’s 600-home scheme, Jones is keen to emphasise, is not just about achieving the passive house mark. “I would never criticise anyone for doing passive houses. But you could live in a passive house with a large driveway and three cars. Our developments are about supporting a sustainable lifestyle in all of its facets — sustainable transport, being well connected and minimising the need to travel, as well as the houses being very energy efficient, and having the renewable technology to generate power on top of that.”

City of York Council began its 600-home project in 2017. At the time, the council owned several vacant sites and was facing an ongoing affordability crisis, with demand for housing outstripping supply. House prices are relatively high for the north of England. When adjusted for income, properties are similarly expensive to parts of the southeast.

We’ve created raised beds for shared growing.

The first 88 homes on the first site, a 165-home project at Lowfield Green, have already been occupied and the rest will be completed by late 2022. They were designed by BDP’s Sheffield office and are mixed tenure, with 40 per cent social rent and shared ownership allocations, and 60 per cent private housing sold under the Shape Homes York brand. But with the next stage of development, York wanted to go much further and build zero carbon passive houses.

Fifty architectural practices submitted bids and Mikhail Riches was appointed a week before winning the 2019 Stirling Prize for the ground-breaking Goldsmith Street, a certified passive social housing scheme in Norwich which featured in issue 32 of Passive House Plus. “I wasn’t familiar with the practice before their submission, but we visited Goldsmith Street and thought it was fantastic,” said Jones. “When they won the Stirling Prize, it gave us a lot of confidence we were right to take the next step on from Lowfield and build passive houses, incorporating PVs, air source heat pumps and renewables that take it to zero carbon.”

When David Mikhail, co-founder of Mikhail Riches, saw York’s advertisement in the Architects’ Journal he found the brief “really refreshing”. He says: “It was the first time I’ve seen a call for our services that suggested the client thought as we do and used the same language. It’s rare you get asked questions that – because you absolutely know your stuff – you’re desperate to answer. Rather than the usual mind-numbingly tedious brief, York were asking questions like ‘how would you go about making places suitable for pedestrians and cyclists rather than cars?’ and ‘how would you make a really great place to raise a family?’ It was aspirational design. So, they got it right from the beginning. And that was before the new councillors came into power a short eightytime later and became even more ambitious, targeting zero carbon. I don’t know another council targeting both zero carbon and delivering such high-quality homes.”

York councillor & executive member for housing Denise Craghill visiting site with Caddick Construction director of housing Richard Greenwood

Pictured at Duncombe Barracks site, where public engagement boxes were placed are (l-r) Mikhail Riches senior architect Sophie Cole, ImaginePlaces founder Angela Koch, councillor Craghill and City of York’s head of housing delivery and asset management Michael Jones.

The DNA of the York developments, Mikhail says, is similar to the Norwich passive houses. In Norwich, there are shared children’s play areas at the heart of the communities and a similar idea is being developed for York on a bigger scale. Mikhail says: “But in Norwich they were just ginnels, slightly enhanced alleyways, whereas in York we’ve been more ambitious and generous. We’ve created raised beds for shared growing. At all stages, Michael and his team have an eye on creating first-rate places to live.”

There has also been more local engagement and consultation at York. The council hired Angela Koch, from planning consultancy Imagine Places, to connect the design team and client with local stakeholders. The team met local businesspeople and residents to do demographic analysis of areas, then spatially map out facilities and services. They then held workshops with residents in local churches or community centres. “We used building blocks representing houses, or trees, or cars, and asked residents to move them around. The community became part of the design process detailing each project’s objectives and working with the design team to build it. They had to make all kinds of tradeoffs and we found that residents pushed us towards having more trees, more green space and fewer car parking spaces. Given York is such a flat city, it’s a place you can live happily without a car, although we’re trying to put in car hire in every site. You can have a car for a few hours rather than one that sits on the driveway 90 per cent of the time.”

The first two zero carbon sites designed by Mikhail Riches are at Duncombe Barracks, on Burton Stone Lane in the Clifton ward, and Burnholme, in the Heworth ward. Both developments have planning permission and Jones has signed a contract with Caddick Construction to build them. Construction of Duncombe Barracks’ thirty-four homes, and one commercial unit, will begin this summer and is expected to take 18 months.

Car use is discouraged; every home has a bike shed.

Meanwhile, the construction of the eighty-three Burnholme site homes will follow on a few months later. A third project on Ordnance Lane with eighty-three new homes has just won planning approval. More sites are under discussion and will follow.

Each location has a mix of one-bedroom flats and houses of various sizes. Currently 40 per cent are affordable homes, which is roughly half council housing and half shared ownership. But Jones says the council wants to get grant funding to increase the number to around 60 per cent of the total. The council has also introduced a priority scheme for key workers. “The vast majority of projects are now mixed tenure. If we did 100 per cent affordable housing schemes, we’d run out of funding quickly. This way the sales’ receipts help to cross-fund the development and it’s not exclusive in any way. It should allow us to keep doing this for years,” he says.

An important element of the inclusivity, he says, is that some of the homes allow two generations of the same household to live independently within them. “Britain is the most age-segregated society in Europe and we’re passionate about creating communities with mixed demographics. With some of the homes, the ground floor is a self-contained flat, so the property will have two separate kitchens. The living room will have a connecting door to the main house upstairs which will support the larger family.

This type of co-living could be suitable for grandparents, who might want their independence, but also need to be close to their family for support. It allows flexibility and you get the benefits of the physical strength of younger people with the wisdom of older people.

This article was originally published in issue 42 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

“We feel that this could be a great alternative to a care environment for many families, which our residents tell us is the last resort, but one people often feel forced to take because of a lack of alternative options. This design might also work well for sons or daughters who have come home from university and can’t afford to buy their own home yet, or for other family members with care or support needs.”

The projects aim to encourage sociability to avoid the modern plague of social isolation, says Councillor Denise Craghill, York’s executive member for housing and safer neighbourhoods. “The shared spaces, including the raised beds and the ginnels, encourage socialising outdoors. It’s similar to something we’re seeing in existing Victorian terraces in York which is the greening of spaces between houses. At the front of the houses we’re creating play streets where children can scoot around and people can meet up,” she says. Craghill says it will be interesting to observe how the major house builders react to the high quality of the homes, as well as their extra environmental credentials.

Another aspect of the scheme which may raise eyebrows among house builders and planners alike is density, with Burnholme, Duncombe Barracks and Ordnance Lane respectively delivering 40, 52 and 62 dwellings per hectare, chiefly consisting of two-storey dwellings, along with some three-storey apartment buildings. (By comparison, the Irish government’s recently announced Croí Cónaithe scheme to support developing apartments for owner-occupiers requires a minimum density of 35 units per hectare – and a minimum of four storeys). “The differences reflect the different context of the projects,” says Michael Jones. “Burnholme is a very suburban setting and Ordnance Lane is more urban, being a short walk or cycle from the city.”

Mikhail Riches had achieved a remarkable 82 units per hectare for Goldsmith Street, but differing considerations allowed a relaxation in this case. “Part of this is around the client brief for the projects to be landscape- led and we are delivering more public open space than planning policy requires,” says Jones. “I was at a local plan hearing last week when developers were saying our proposed local plan density targets are unachievable. I think [these schemes] demonstrate that you can achieve high density with national space standards and house sizes, at low heights, and create high quality public open spaces with biodiversity net gain.”

As York is in the north of England, where daylight hours are shorter than in the south and the sun is at a lower angle, Mikhail Riches had to work out how to stop overshadowing from blocking the sunlight in winter. This involved modelling the roofscapes so the sun penetrated the ground floor windows in the kitchens and dining rooms. “It was a lot harder to achieve than Norwich as the angle of the sun is different,” Mikhail says.

In the short term, Michael Jones thinks some councils will be put off building passive houses, and zero carbon homes, because of the higher cost. But he expects it to become more mainstream. “Changes to building regulations will push all new builds to passive house. Costs are a bit of a barrier, but they will fall. A bigger issue is there are so few architects, or builders that have built passive houses. Early adopters like York will help to drive change by upskilling the market and getting our region ready to deliver the standard,” he says.

Embodied carbon

York wanted to reduce the embodied carbon of the construction by avoiding carbon-intensive materials like concrete, while using timber frames. David Mikhail thought carefully about how to fulfil York’s request. “It’s incredibly difficult. Until we decarbonise the industry, we’re not getting low-carbon bricks. Since the Grenfell Tower disaster, it’s hard to get insurance companies to look at anything involving timber. And building control is also anxious about timber. As a result, it’s hard to get a mortgage for a building with, for example, timber cladding or timber decking on a balcony. It means we’re forced down the route of steel, glass and cement. But York has used timber frames for the superstructure and we’ve clad it in either brick, or clay tile. And we’ve used cellulose insulation, such as recycled newspaper, or wood fibre blown-in insulation, which gets the buildings into line with the RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge guidelines,” he says. In this regard, Passive House Plus played a hand, by introducing Mikhail to Tim Martel, creator of the AECB’s embodied carbon calculation tool, PHribbon, who did some consultancy for Mikhail Riches before the project began. Caroline Martin of passive house consultants WARM then used PHribbon, with Martel helping define the scope, to calculate the scheme’s embodied carbon scores.

The scope of the assessment – which focused on three blocks of terraced homes and apartments at Duncombe Barracks – is largely complete, including virtually all elements required for the RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge, albeit with incomplete information for building services (the MVHR system, heat pump, pipework and ductwork included), and fixed furnishings and equipment (WCs, basins and kitchen sinks were included). As per RIBA, external works were excluded. The results are indicative only – default data was used in many cases, or if EPDs weren’t available for a given product in the spec, default values or data from a comparable product was used. Blocks B and C meet the RIBA 2030 target of 625 kg CO2e/m2 GIA, with scores of 595 and 587 respectively while Block A scores 642.

Taking Block A for instance, a large part of the reason for this score is down to what may be regarded pessimistic assumptions about the lifespan of components, and about their end of life. 397 kg of CO2e/m2 are estimated to be released by the point of practical completion (module A). By this point the building is also estimated to be sequestering 197 kg CO2e/m2 in the bio-based materials used such as timber and cellulose.

The use phase (module B) adds a predicted 213 kg CO2e/m2 due to material repair and replacement assumptions. For instance, the PV arrays are assumed to need two replacements within the 60-year reference life for the building, and the heat pump and MVHR system are assumed to need three replacements. In well designed buildings such as these, taking account of what we know about the lifespan these kinds of technologies can achieve, may fewer replacements be more realistic, subject to maintenance? And bearing in mind the strides some manufacturers are already making to radically reduce upfront emissions, is it really reasonable to assume that, say, a replacement heat pump installed 15 or 25 years from now will have similar embodied carbon to machines made today?

The end of life phase (module C) adds a further 230 kg CO2e/m2. Principally, this is because of the assumption that the CO2 sequestered in the timber and cellulose is released into the atmosphere – including the default assumption that the bulk of this material goes to landfill, and breaks down as methane. However as the article on Joe Lyth’s timber frame house in New Zealand demonstrates (see page 8), it is possible – at least based on New Zealand data – to assume the vast majority of sequestered CO2 in landfilled timber does not break down, and remains sequestered. Based on current rules, this would create a curious state of affairs. If timber is reused or recycled at the building’s end of life, the sequestered CO2 in that timber moves outside of the boundary conditions of the building, and passes on to the next use. However if the timber is landfilled, and if it’s assumed not to decompose in the landfill, then the sequestered CO2 needn’t be deducted – creating an incentive to dump rather than reuse timber.

Selected project details

Product details reflect initial specification and are subject to change

Developer: City of York Council

Architect: Mikhail Riches

M&E design: LEDA

Civil & structural design: Civic Engineers

Passive house consultant: WARM

Project management: Turner & Townsend

Main contractor: Caddick Construction

Quantity surveyor: Turner & Townsend

Timber frame supplier: Roe Ltd

Airtightness products: ProPassiv, via Green Building Store; Tremco Illbruck, or equivalent

Brise soleil: Cadisch MDA

Air source heat pump: Valliant

DHW cylinder: McDonald Water Storage

Steel panel radiators: Stelrad

MVHR: Zehnder

Pitched roof PV: Viridian

Flat roof PV: Bisol

Blown cellulose: Warmcel, or equivalent

External wall insulation: Permarock, or equivalent

EPS insulation: Jablite, or equivalent

Mineral wool slabs: Knauf, or equivalent

Windows & doors: Idealcombi, or equivalent

Clay facing brickwork: Crest BST, or equivalent

Lime mortar: Limetec, or equivalent

Oak flooring: Tarkett, or equivalent

In detail

This information panel focusses on a 111 m2 terraced two-storey three-bedroom house at Duncombe Barracks, York, part of a wider mixed-tenure development of thirty-four homes designed to the passive house standard. This development will have a range of sizes and types including eleven one-bed flats, eight two-bed terraced houses; nine three-bed terraced houses, and six four-bed terraced houses. Energy performance metrics are targets rather than measured figures. Product details reflect the initial specification and are subject to change.

Building type: A typical 110.71 m2 terraced two-storey, three-bedroom house

Location: Duncombe Barracks, Burton Stone Lane, York

Completion date: December 2023

Budget: £13.69 m including land, works and on-costs for the whole development including thirty-four homes, one commercial unit, and high-quality public realm that comprises a central green space and a small civic square.

Passive house certification: Aiming for PH classic standard

Space heating demand (PHPP): 15 kWh/m2

Heat load (PHPP): 10 W/m2

Primary Energy Renewable (PHPP): Aiming to be below the PER limit of 60 kWh/m2

Heat loss form factor (PHPP): 2.24 for the whole terrace (comprising houses & flats)

Overheating (PHPP): Designed for 0 per cent Number of occupants: 5-person household in this example; 141 at Duncombe Barracks in total.

Environmental assessment method: Aiming to achieve carbon net zero in operation in line with the LETI framework.

Airtightness (at 50 Pascals): 0.6 air changes per hour

Predicated energy consumption: 35 kWh/m2/yr

Energy bills (estimated): As low as £300 per year based on domestic energy costs from 2021. Based on PHPP estimates, City of York Council estimates that this example property could have a total electricity bill of £300. This includes standing charges but also savings/feed-in-tarriff from the solar PV array. The council says that this should be considered, “a very estimate as it is impossible to predict occupier behaviour. It could be considered an ambitious target that can be achieved with the right education and support.” Thermal bridging: Thermal bridge values have been assumed for step backs, balcony structures, internal walls to floor and party wall to floor junctions. These are currently based on details from previous projects and will be calculated at the next stage if necessary. All other thermal bridging has been designed out. Preliminary calculations have been undertaken for window installation values; these will be further refined at the next stage if required.

Ground floor: 75 mm reinforced concrete topping, followed underneath by Visqueen vapour barrier, 225 mm Celotex foil-faced PIR board (thermal conductivity 0.022 W/mK), Visqueen EcoMembrane loose-laid polyethylene DPM, 225 mm Jetfloor insulated beam and block floor system (Infill blocks: 150 mm EPS grey insulation blocks; thermal conductivity 0.030 W/ mK), 250 mm void, 750 x 900 reinforced concrete footings. U-value: 0.083 W/m2K

Walls: 102.5 mm brick on 50 mm cavity; or 7 mm PermaRock silicone render on 140 mm PermaRock mineral fibre insulation; followed inside by breather membrane (Pro Clima Solitex Plus), 400 mm timber frame construction with 380 mm Warmcel insulation, 13 mm Smartply Propassiv board as airtight layer, 45 mm cavity insulated with Knauf Earthwool, 15 mm plasterboard and skim. U-value: 0.097 (brick cladding build-up) and 0.80 (silicone render) W/m2K

Pitched Roof: Clay Pan Tile, followed underneath by battens & counter-battens, breather membrane (Pro Clima Solitex Plus), 400 mm timber frame insulated with 380 mm Warmcel insulation, 13 mm Propassiv Board used as airtight layer, 45 mm cavity insulated with Knauf Earthwool, 15 mm plasterboard & skim. U-value: 0.097w/m2K

Flat roof: IKO Spectratex polyester protection fleece, followed underneath by 200 mm / 300 mm IKO Enertherm tapered PIR roofboard, IKO Systems metal-Lined bituminous VCL, 25 mm plywood (WBP) & OSB3, 150 mm Knauf Earthwool, 400 mm timber frame with 380 mm Warmcel insulation, 13 mm Propassiv Board used as airtight layer, 45 mm cavity insulated with Knauf Earthwool, 2 x layers 15 mm plasterboard, skim. U-value: 0.0106 & 0.072 W/m2K (depending on PIR insulation depth).

Windows & external doors: Ideal Combi Futura+ triple glazed aluclad windows and doors. Heating system: Vaillant AroTherm Plus 3.5 kW air source heat pump with seasonal efficiency of 365 per cent supplying low temperature radiator heating system and a super insulated 180 litre domestic hot water cylinder.

Ventilation: Zehnder heat recovery ventilation systems. Water: Rainwater harvesting via water butts. Low flow fittings on all plumbing fixtures. Electricity: 22 m2 Clearline Fusion PV system with average annual output of 5 kW per dwelling. No on-site storage, excess electricity will be exported to the grid.

Green materials: Cellulose insulation, timber frame construction. Transport: Low number of car parking spaces, car clubs, free-to-hire e-cargo bikes, generous bike storage.

Image gallery