- Insight

- Posted

Delivering passive house at scale

Dublin is on the verge of taking a giant leap forward for construction, with two major authorities in the region set to make the passive house standard mandatory for new buildings. Can Ireland’s mainstream building sector rise to this challenge, and what can it learn from experience of big passive house projects across the water in the UK?

This article was originally published in issue 14 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

From March on, all new buildings in Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown will be required to meet the passive house standard — or an equivalent level of energy efficiency — under requirements set to come into force in the Dublin region’s latest development plan. Meanwhile Dublin City Council has voted to include a similar ‘passive house or equivalent’ clause in its draft development plan.

Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown’s draft development plan lists a housing allocation of 33,600 homes to be built by 2022. Once the existing planning permissions for more than 5,000 units and the 7,700 homes allocated to the area of the Cherrywood strategic development zone are excluded, given that the new development plan won’t apply in either case, the total is closer to 20,000 new homes. That said, the developers at Cherrywood may see the business case for voluntarily going passive, or risk competing poorly with adjacent new property built to quality-assured high performance levels.

Overall, Ireland’s Economic and Social Research Institute estimates that the Dublin region will need 60,000 new homes by 2021. If the various local authorities are successful in adopting the passive house standard (environment minister Alan Kelly can still attempt to veto the plans, though this looks increasingly unlikely) a large swathe of Dublin’s new housing may be passive, and most of these dwellings will probably be built as part of large social or private housing developments.

This begs a question: how can a building industry that, before Ireland’s construction boom, was largely known for leaky and energy inefficient housing adapt to a new reality in which it has to meet one of the world’s most energy efficient building standards, and across thousands of homes and other buildings?

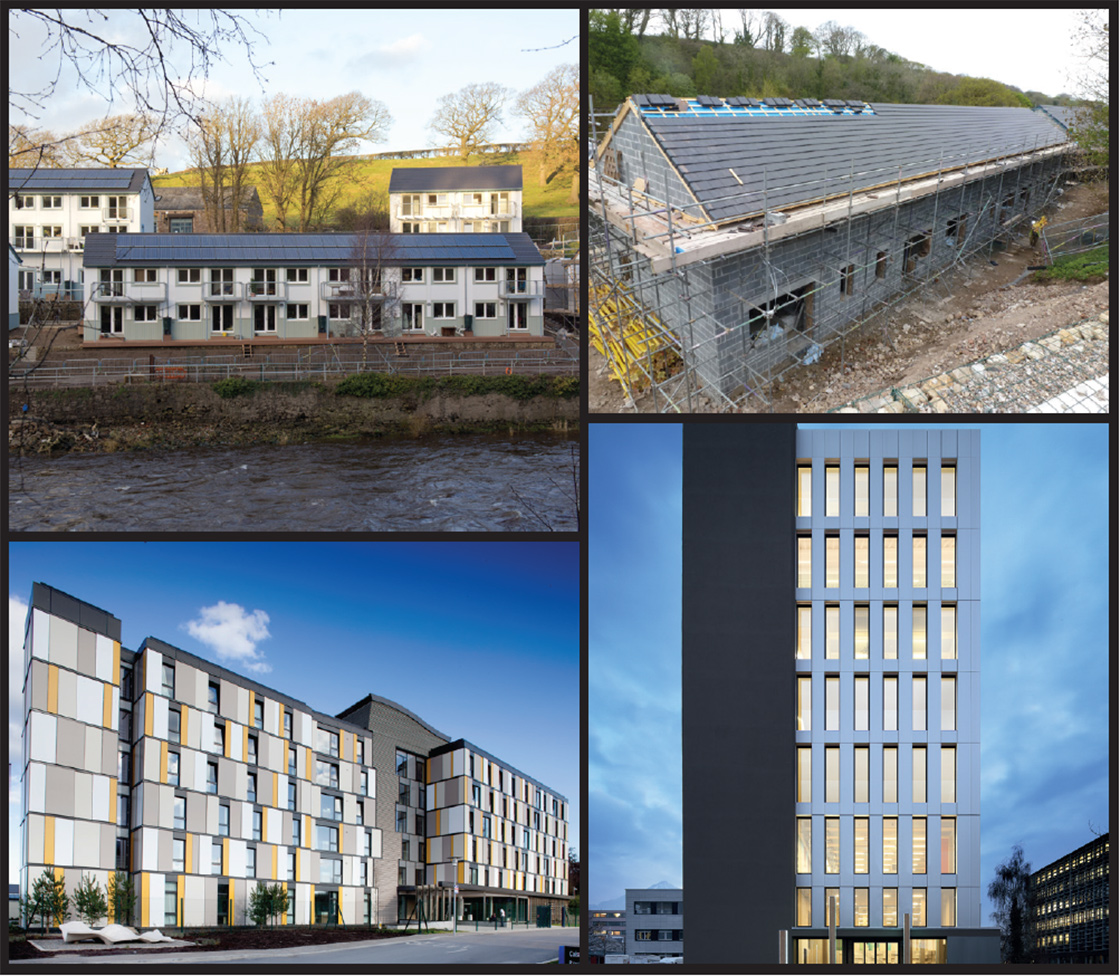

Large scale passive house projects are becoming increasingly common in the UK such as Octavia’s Sulgrave Gardens mixed tenure scheme and Hastoe’s Ditchingham affordable housing scheme

Pat Barry, an architect and executive director of the Irish Green Building Council (IGBC), believes it will be a challenge. The IGBC is one of the partners behind the EU-funded Qualibuild project, which is delivering free training in low energy building skills to construction workers. But Barry says the take-up has been disappointing so far given Dublin’s move towards passive house, and the EU’s demand that all new buildings be ‘nearly zero energy’ from 2021 on.

He also believes the way large-scaled projects are managed may be an inherent obstacle to achieving the passive house standard: contractors hire subcontractors who in turn hire their own subcontractors, making it difficult to vet labourers on site for low energy building skills.

“Contractors are just engineers sitting in offices project managing,” he says. “They are several subcontractors removed from the chap installing the insulation.”

If a new tradesperson is needed, a contractor will often call a recruitment agency, who will most likely know nothing about energy efficiency, and simply check that the labourer has a Safe Pass (Ireland’s health and safety cert for construction workers). Barry suggests a more dynamic approach, whereby tradespeople carry a card that lists all of their qualifications, including passive house and low energy building skills.

“We’re trying to get the message out to contractors first, and then the recruitment agencies,” Barry says. The same challenges exist in the UK too, even though the country is witnessing a growing number of residential passive house developments, often driven by housing associations and local authorities. But Passivhaus Trust executive director Jon Bootland says there is still much to learn for large-scale developments.

“On the small-scale passive house projects we find there is typically one person who is incredibly enthusiastic, and they act as a quality assurance driver, and put in a lot of extra mentoring and support and quality checking. And that’s fine on a small project of up to ten units,” Bootland says.

But on larger projects it’s simply impractical for one passive house champion to check everything — deeper quality control measures are needed across the site. He says there are three areas where things tend to go wrong on bigger projects.

The first is where the main structure of the building meets the foundation — continuity of the insulation here is critical. The second is the quality of the installation of the insulation itself. “On non passive house projects you’ll often find the above ground insulation isn’t continuous,” he says. “If you’ve got a gap in the insulation it’s almost worthless.”

“The third thing is to do with the installation and commissioning of the services, particularly the ventilation system,” he says. He points to the very high failures rates for ventilation systems installed in non-passive house projects, with research showing that many do not deliver enough fresh air.

He says large-scale passive house projects need a quality control system that checks these three items — and checks them at the time they’re being done on site, not when the project is finished. This doesn’t mean reinventing the wheel — contractors just need to build passive house into existing quality control systems.

The UK has about 400 certified passive house designers, but far less trained passive house builders. Bootland believes there’s a danger that, if contractors price early passive house developments too high because they perceive it to be riskier, it might scare other developers off adopting the standard.

“That could slow down the uptake of passive house. What some clients have done is set a fixed price and made passive an absolute, and said: ‘Go away and find out how to do it,” he says. “We want people to realise it is more onerous building a passive house — but you’ve got a better quality product at the end of it.”

Many of the the passive house advocates that Passive House Plus spoke to for this article argued that, to build passive housing on a large scale, the industry would ultimately need to embrace a big change: moving the bulk of construction from on-site to in-factory prefabrication, particularly for large multi-unit projects.

The word ‘prefabricated’ can often be misinterpreted as ‘timber frame’, but concrete buildings can be largely prefabricated too — think of large precast concrete panels. Over the last few years we’ve seen the first ever examples of 3D printed buildings, as pioneered by Chinese company Winsun, whose giant 3D printers use a mixture of construction waste, sand, concrete and fibreglass to print hollow walls that can then be insulated on site. If cars are precision engineered in sophisticated factories, shouldn’t buildings be too?

(clockwise from top left) While the likes of Lancaster Cohousing prove that traditional cavity wall construction can be used on substantial passive house projects; ground-breaking off-site build methods such as the timber structure for the eight storey certified passive Life Cycle Tower 1 office building in Austria may help to deliver substantial buildings at scale in the midst of a skills shortage

Bottom right photo: Norman A. Müller / nam architekturfotografie | Bottom left photo: Paul Tierney

“The idea of bringing off a lorry load of blocks, a lorry load of sticks of timber, and then trying to cut that and build a quality assured house on site, is really over,” says Pat Barry. “From a construction worker’s point of view, the idea of being out in the wind and rain, trying to put together a high quality product, doesn’t make sense.” Manufacturing quality assured products, he says, demands a comfortable production environment with proper lighting and climate control.

Leading London-based passive house architect Bram de Bruycker agrees. “Prefabrication allows you to have much better quality control on several points like insulation, draft proof construction and building in windows — and on top of that it solves problems of high labour costs and lack of skilled people that the industry is struggling with,” he says.

He also sees prefabrication as a route to designing and constructing each project as a whole — with orientation, the building envelope, airtightness and services all integrated — rather than each of these being engineered separately on site.

In Ireland and the UK, with a long-established culture of block-building on site, prefabrication is unlikely to become the norm overnight. But builders who want to continue working on site may simply need to embrace evolution rather than revolution: for example, a single-leaf block or precast concrete wall with external insulation, and wet plaster inside for airtightness, is arguably much simpler to detail and build than the first example – a cavity wall partially filled with an insulation board, with additional insulated plasterboard internally – provided by the Department of the Environment on how to comply with Part L.

Right now, the Irish construction industry is waiting to see how the passive house requirement in Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown will be implemented.

Will it be the planning officers, who typically don’t have much technical construction knowledge, who are required to enforce it? Or will it be building control departments — which are poorly resourced and currently inspect only 12 to 15% of buildings each year? Or could the work be contracted out to an external certification body?

Regardless, Passive House Academy founder Tomás O’Leary is optimistic about Dublin’s ability to meet the challenges of delivering passive houses on a large scale. He points out that, unlike many other countries, Ireland has plenty of passive house designers — plus a mature supply chain of passive house products.

“I think on the knowledge side of things, we’re a bit like a seed bank that’s waiting for a shower to come along,” he says. “Ireland has a lot of certified passive house designers and a lot of certified passive house tradespeople. We’ve been out in the desert in terms of construction for the last seven or eight years, we’re just waiting for the thing to come back.

“The skills are there and they’re available to be tapped into.” He points out that the relatively one dimensional climate and mild weather of the UK and Ireland, with our short cold season, means passive house is easier to deliver here too — passive houses simply don’t need to hit the same U-values as in Central Europe.

“In Ireland, I think we’re actually well positioned,” he says. “We did build the first certified passive house in the English speaking world [O’Leary’s own house]. We’ve been at this a while.”

When Passive House Plus studied Ireland’s building energy rating data last year, the average new house in Ireland was achieving an A3 building energy rating, with calculated wall, floor and roof U-values between 0.14 and 0.17 — not far off passive. Granted airtightness was averaging 3.8 m3/hr/m2, but this was a vast improvement on the average figure of worse than 10 m3/hr/m2 from homes built during Ireland’s building boom. The Irish building industry has upped its game — it just needs to keep going.

It’s natural, O’Leary says, for developers and contractors who have no experience of passive house to be a bit fearful of of it. “There was a fear or concern, unfounded, that passive house would drive the cost of construction up, and that it would grind everything to a halt. But he points to developer Michael Bennett’s passive house scheme in Enniscorthy, Co Wexford as an example of what can be achieved — timber frame, semi-detached passive houses within the Dublin commuter belt that were built in seven weeks, and are now on the market for just €170,000.

“You can’t unsee passive house,” he says. “Once you’ve been exposed to the details, the materials, the products…you can never unsee that.” He says the Passive House Academy is starting to see an upsurge in people attending courses as designers and tradeseople start to prepare for a new reality.

“In the last six months, we’ve seen developers sticking their heads above the parapet again,” he says. “Whether it’s passive house or NZEB, they know that the bad old days are finished.”