- Insight

- Posted

Reimagining the architect

It’s a radical idea: that to negate the environmental damage of construction, we don’t just need to build sustainably, we need to build less. However, most architects and building designers earn a living by doing exactly the opposite: by building stuff. So how can the design practice be reinvented for a world in which we need to do more with much, much less?

New York architect Clare Miflin likes to tell a story about an engineer she knows.

This article was originally published in issue 48 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

The engineer was consulting for a leading university, who were keen to build a new, green ‘net zero’ building on campus. The engineer told the university that if they just made some timetable tweaks, they wouldn’t need the new building at all — they could fit all their lectures into existing classrooms. But the university had a donor, and the donor was keen to see their name on this new green building. So, the building went ahead.

In this climate constrained world, Miflin says, there must be a better way. “We have to start rewarding different things, rewarding things that add value,” she says. “We want jobs, but we don’t want to use physical resources. Could architects be paid in a different way?”

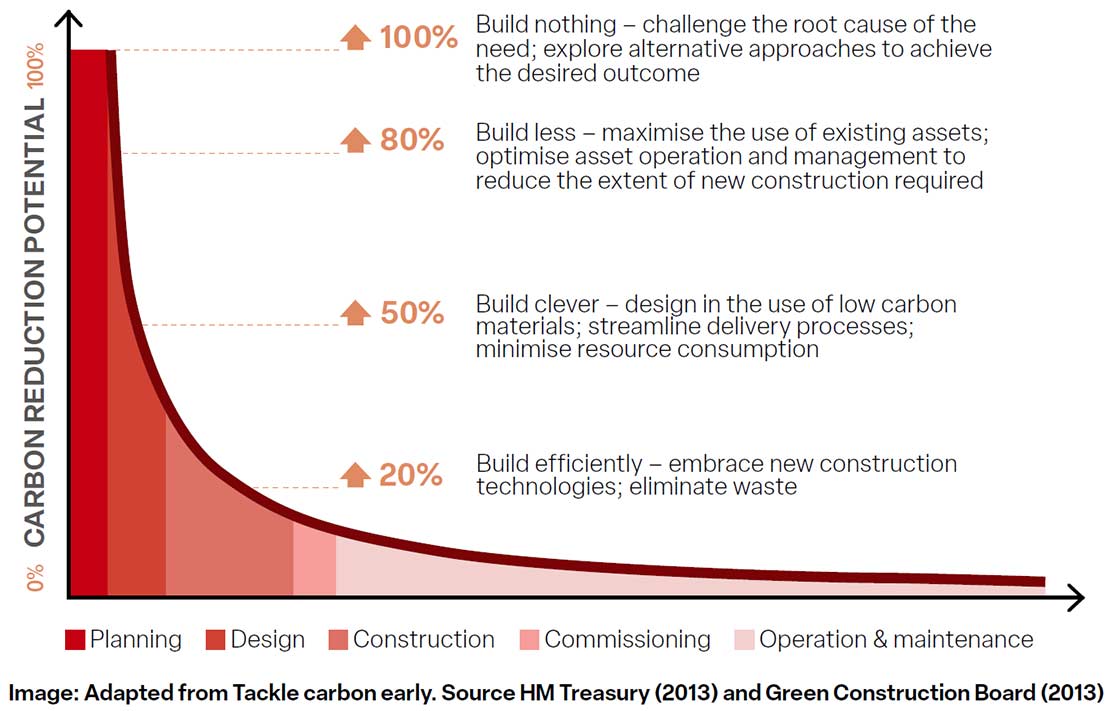

Emerging thinking says that the climate and ecological crises are so profound that ‘sustainable building’ is no longer sufficient — instead, we should question the merit of new buildings, make better use of existing space, prioritise retrofit. ‘New’ should be our last resort. This is reflected in new initiatives from the likes of ARUP and the World Green Building Council, and more recently, articles in leading magazines.

Last year, UK housing secretary Michael Gove refused Marks & Spencer permission to demolish their flagship Oxford Street Store in London, partly because demolition would, he wrote, “fail to support the transition to a low carbon future, and… fail to encourage the reuse of existing resources” (this decision was later overturned by the High Court).

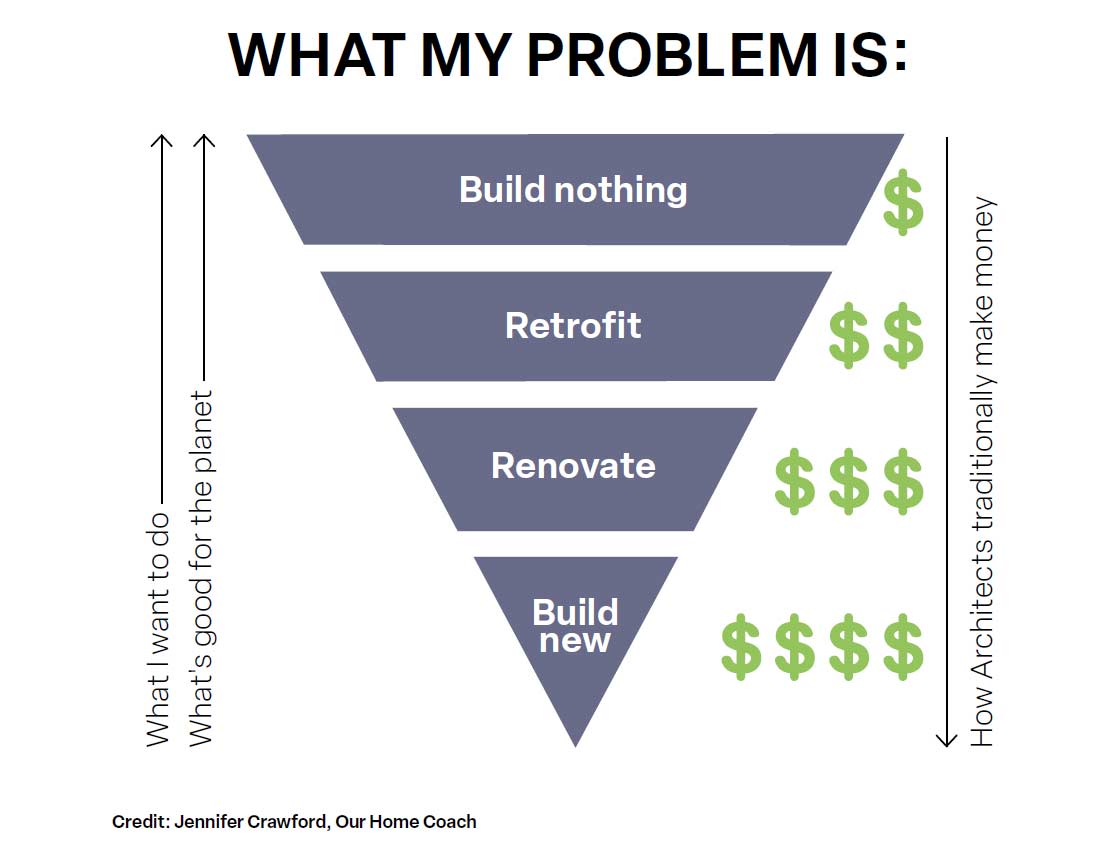

For those working in building design, the idea of building less raises critical questions: if we traditionally make money by building more, how can we make money by building less? What architect ever earned a buck by convincing a client not to build something? This problem was neatly surmised in an image posted to Instagram by Australian architect Jennifer Crawford in 2022 (hat tip to Lloyd Alter who first wrote about Crawford’s work).

Getting to net zero would have been easier if we increased our footprint, limited occupancy, and outsourced as many impacts as we could. But would that have made the project more sustainable?

Crawford previously worked in residential development, but in 2020 she started her own design firm — with a twist. Our Home Coach helps clients to meet their needs not just by building homes and extensions, but by applying good design to do more with less. Most of Crawford’s clients are homeowners looking to renovate.

“I talk people out of doing a lot of stuff,” she says, “because I know how hard it is, how long it takes, how much money it takes.” She says that in Australia, many clients are keen to scale down their renovation plans because the price of construction has skyrocketed.

“The solution is not always a building solution,” she says. “Sometimes it’s a landscaping solution, sometimes it’s a furniture solution. Sometimes you can rearrange furniture in a room and turn one space into two.”

In researching this article, we spoke to a number of architects and other built environment professionals about how architecture might change in a world where we need to build less, and the phrase that kept coming up was ‘adding value’. Can designers add value to their clients’ lives and buildings, without adding floor area?

Crawford offers a practical example: a client had a disused garage they wanted to convert into a guest suite and office. The roof was very low, and the client, who is tall, found the space cramped. Their plan was to add a second floor, creating two separate spaces. But Crawford proposed a smaller, cheaper solution: raise the roof slightly, install skylights, a drop-down wall bed, and a drop-down wall desk. The building was thermally retrofitted too. Now the same room can serve as an office, bedroom, or sitting area, depending on which furniture is in use. “The footprint stayed the same, and now they’ve got three rooms in the space of one. In my mind that’s adding value.”

In 1996 Lacaton & Vassal won a commission to redesign Place Léon Aucoc, Bordeaux, and ended up recommending doing next to nothing, as it was already perfect.

Another example: the French architectural practice Lacaton + Vassal, who won the Pritzker prize in 2021 and whose motto is “never demolish”, were asked to redesign a small square in Bordeaux. After observing the square closely and speaking to locals, they recommended that the city do almost nothing to the space — it was already close to perfect. “Embellishment has no place here,” they wrote. “Quality, charm, life exist. The square is already beautiful.” They recommended basic maintenance work: replace the gravel, clean the square more often, adjust traffic management slightly.

“We don’t add value if we skimp on the dishwasher and then truck disposable plates to landfills 350 miles away,” Clare Miflin writes of designing a cafe. “We do if we realise the building doesn’t need its own auditorium because there is one next door that the client could share.”

This philosophy creates a whole new set of questions for designers to ask: How can we reduce the waste flows from this building? How can we get more from the existing space? Do we really need to extend? Could we make the design smaller, even ask our neighbours to share some facilities?

This might not be the design work that architects are accustomed to, but it is design. “I think there is so much of a role for architects because they can think systematically, and design solutions in a systematic way,” Miflin says.

Having previously worked for conventional design practices, she established her consultancy ThinkWoven in 2018, and the non-profit Centre for Zero Waste Design, in 2019. The focus of both is to design circular flows for materials through buildings. Neither is a conventional architectural practice, but Miflin prefers to hire architects because of their ability to think systematically and solve problems with good design.

She says that ideally, architects would be engaged much earlier in projects — even before site selection — to find ways to reduce the use of resources from the outset. And they would stay involved long after occupation, to fine tune the building and oversee post-occupancy evaluation. “Right now, architects get no feedback from projects to help them design better,” she says. (In Scotland, John Gilbert Architects set up an office dedicated to building performance evaluation as part of their response to climate breakdown, and now build this service into all of their projects).

As we confront the planetary crisis, could the focus of design shift from creating new buildings to designing communities and systems that regenerate the living world? How can communities organise themselves to provide for food, shelter and transport in a carbon- constrained world? This requires good design. (The work of the Australian permaculturist David Holmgren to reimagine the suburbs of Australia touches on this).

“I’ve done a lot of community engagement and community design work,” says architect Marianne Heaslip. “Some of the joy in that is helping people to figure out what they want, working out the context of an existing building, making it a good place to be — but also making it function from a thermal point of view. I think some of the best designers and architects, that’s what they’re about.”

In 2009, after she was laid off from her role with a conventional design practice, Heaslip used her redundancy to pay for a masters in retrofit at the Centre for Alternative Technology in Wales. She’s now technical director at People Powered Retrofit, a not-for-profit community benefit society that works with householders, contractors, and housing providers to facilitate high quality retrofit.

Perhaps one of the most forward-thinking pieces of design ever published in these pages: The Beehive, originally published in issue 24 of Passive House Plus. This derelict newsagents was reimagined by C&O Architects as an ecologically-insulated 45 m2 home in Shrewsbury, squeezing every ounce of utility out of a small space. While not Enerphit certified, revised PHPP calculations by passive house consultant Nick Grant for the case study in light of a methodological update to take account of higher internal gains in smaller homes meant the building likely comfortably met the standard. Finished photos: Dan Farrar

“We do early-stage surveys and options studies for domestic retrofit using our Home Retrofit Planner tool,” she says. “By providing the comparison and contextual information, we have been able to convince a client on a few occasions to forgo the extension they had planned and instead go further with the retrofit elements of the work, so they had a more comfortable and functional home, or could more affordably run a heat pump. It's not always possible to make that case, but it's getting more common that sufficiency is seen as important as efficiency. And when it comes to work for an architect, there can be as much to do in a considered whole house retrofit as a standard extension”.

Heaslip says that shifting focus from new build to retrofit will change the nature of architecture somewhat. “A lot of people see architecture more like an art-based discipline, rather than a maths one or an engineering one. But I think a lot of the skills called for in low carbon sustainable building or retrofit are a little more science based.” Budding architects and design professionals will need to understand building physics, heat, moisture, and embodied carbon.

“Architects will get more creative and more specialist in existing building types and moisture management,” say Retrofit Action for Tomorrow (RAFT), a new London-based design practice with a focus on decarbonisation and climate resilience for schools. “Existing buildings need thoughtful specialist design, finding low intervention spatial solutions that work with and enhance [them].” But to facilitate this, architectural education needs to change and focus more on retrofit, they say.

The question remains: can architects and designers make a good living in this new world of building less?

Changing how we evaluate buildings can swing the pendulum too. “We celebrate excessively large passivhaus projects when they use as much energy as a moderately performing three-bed house,” say RAFT. “We extend so much when we retrofit that we wipe out the carbon savings gained by retrofitting.”

Instead, they say, we need a celebration of spaces that work hard for their size, of sensible retrofits, of normal looking projects that prioritise comfort and function over aesthetic and luxury.

Building metrics need to evolve too, Clare Miflin says. Energy consumption and embodied carbon are typically measured per square metre of floor area, meaning a building can be far larger than needed and still meet benchmarks like the passive house standard or the RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge.

Miflin writes of an environmental centre she designed: “We had to fit the café’s energy use within the energy budget provided by the solar roof. Getting to net zero energy would have been easier if we increased our footprint and roof area, limited the occupancy of the building, and outsourced as many impacts as we could. But would that really have made the project more sustainable?”

Instead, if we also measured energy use or embodied carbon per occupant, it would be harder to certify a 300 square metre house occupied by just two people. Miflin mentions a project she’s consulting on where the design is based around ensuring each occupant can live within a fair ecological footprint.

“They had to drop the 140 m2 hotel rooms from the plan because they couldn’t make them fit within that metric,” she says.

Australian architect Jennifer Crawford talked a client into making the most of a disused garage, with a renovation and retrofit to create a multifunctional space rather than adding a storey and creating two separate spaces, including a drop-down wall bed, and a drop-down wall desk.

We also need to think hard about the public value of buildings, she says. “Should you get positive metrics for designing a building for a hedge fund, for example? I have designed greenhouses for schools that are hard to make energy efficient, given the constraints of greenhouse forms and technologies, but when you see how excited the kids are in those spaces — learning about plants, food, and ecology — you know the greenhouse has almost certainly had a net positive environmental impact.”

But still, the question remains: can architects and designers make a good living in this new world of building less? Jennifer Crawford admits this has been the “tension” for her practice since she established Our Home Coach. Because she talks her clients out of doing big projects, she needs more clients to make a living. “How do I make money? This is still my challenge,” she says. “My intention is, I don’t want to build more if more does no good, but I will build more if more makes sense.”

RAFT are optimistic about the future.

“Architects’ jobs… will always be in demand, if we collectively organise toward a profession focused on retrofitting cities that are socially and climate justice focused,” they say. “We cannot solely rely on the market and interventions within the market to provide this for the architect. The possibilities for retrofitting cities — on a physical and social level, toward climate, disability, economic, and social justice — are incredibly exciting, as the architect positions themselves within a wider community of engineers, teachers, social workers, artists and health professionals. Our issues are all interconnected.”