- Wastewater

- Posted

The Self-Sufficient Site

The prolific rate of construction in Ireland is starting to take a massive toll on Irish water supply as creaking infrastructure struggles to keep pace with property development, often resulting in pollution where building work continues, and long planning delays whilst local authorities try to bring mains connections to sites. With the expected introduction of water charges next year, Construct Ireland’s John Hearne discovers the growing shift towards making sites independent in terms of both water supply and wastewater treatment.

Global water supplies are in crisis. One in five people doesn’t have access to clean water. Aquifers from the US to Africa to Australia are drying up as industrialisation and population growth outstrips replenishment. London is reportedly drier than Istanbul and in the south east of England, there is less water available per person than in Syria or the Sudan.

But here in Ireland, everything’s ok isn’t it? One thing we’ve an abundance of is water, right? Wrong. In May, The Sunday Times reported that a €1bn housing development in South County Dublin faced a delay of up to five years because of overstretched water supplies in the Dun Laoghaire/Rathdown borough. The unprecedented rate of development the area has seen in recent years has meant that the water needs of Castlethorn’s planned 2,200 home estate in Shankhill could not be met and a delay of between two and five years was on the cards.

This is not an isolated development. Local authorities that have chosen to facilitate development and then play catch-up with supporting infrastructure are finding out that it’s a risky strategy.

In Longford for example, the county council has been switching off the mains at night in order to replenish reservoirs run down during the day. In Dublin, authorities are weighing up a €600m plan to pipe water all the way from the Shannon and another to build a €590m desalination plant in the north of the county. While problems are particularly acute in urban areas, rural Ireland hasn’t escaped unscathed. “The last few weeks showed the extent of the problem,” says Brian McDonald of the National Federation of Group Water Schemes, “with water rationing in Cavan, Meath, Louth…There was a serious issue of depletion of sources.” Of the 1m households in the country, one fifth are not connected to the public water supply. The majority of these – around 150,000 – are serviced by group schemes. Part of the problem, McDonald believes, is waste. “We want people to think about water. The difficulty in the public schemes is people have absolutely no incentive to think about water. You can leave the tap running twenty-four hours a day and it’s not going to cost anything.”

Not for long. Ireland is the only country in the OECD that doesn’t levy domestic water charges. In Northern Ireland, homeowners will face household water bills of £115 (€169) this year, rising to £340 (€500) within three years. In parts of Germany, they’re paying €45 for a cubic metre of water. The current government, mindful of the furore that erupted over bin charges, has insisted that domestic water charges are not on the current programme for government. That programme is due to run out in the next twelve months. Moreover, under the European Water Framework Directive, we have to start charging households for water use by 2010. According to the commission: “Adequate water pricing acts as an incentive for the sustainable use of water resources and thus helps to achieve the environmental objectives under the Directive. Member States will be required to ensure that the price charged to water consumers - such as for the abstraction and distribution of fresh water and the collection and treatment of waste water - reflects the true costs.” Exactly what those ‘true costs’ are isn’t easy to determine, so it’s equaly difficult to say exactly how much we will have to pay when charging is introduced. The experience of the commercial sector, where water charging has long been in place, gives no clue. A survey from IBEC produced two years ago found wild variations in the charging structures of local authorities. A business operating in Longford paid €7.95 per 1,000 gallons of water while a similar business based in Sligo paid €2.79. Limerick County Council was found to have increased its water charges by 135% between 2000 and 2004 while Cavan and Leitrim County Councils kept charges unchanged over the same period.

Meanwhile, across the water in the UK, there are increasing concerns over affordability of domestic water supplies. Last year, the water industry calculated that 9% of households spent more than 3% of their annual income on water and sewage bills. And as far as the future is concerned, the only way is up. Dr. Glynn Hyett of 3P Technik in the UK is keen to draw attention to the energy component of delivering a litre of water to the end user. “That energy cost is a big big factor. The price of water is going to shoot up in the next five years, in Ireland as well, because once you introduce the charging, the directive says you must allocate the true cost of the water. It can’t just make a nominal charge, it must reflect the environmental and economic cost of supplying it.”

Caught in the horns of overstretched infrastructure and the inevitability of charging, both developers and self-builders have begun to take matters into their own hands. With millions of gallons of free water falling from the sky all the time, or what feels like all the time, rainwater harvesting has begun to find a large and growing constituency. The sector has recorded 100% growth in the UK in the past twelve months, while a straw poll among harvesting system suppliers here in Ireland indicates an industry overrun by demand.

“Not all water used in the house has to be purified to the extent that it can be used for drinking.” Says Grainne McGuire of Bord na Mona. The company recently entered the rainwater harvesting market with its Rainsava system. “With the abundance of rainwater and our ability to harvest that from the roofs of our houses, certain items in the house could use less purified water. They account for over half of the water usage in a typical household. Things like toilet, washing machine, water used for gardening, washing cars, things like that…These are what the rainwater system will supply.” All harvesters are based on the same principle. You capture the water coming off the roof in the conventional way, channel it all via a filter to an underground storage tank and from here pump it into the house. The natural softness of rainwater facilitates a perfect fit with appliances like washing machines. The absence of limescale build-up substantially lengthens the lives of white goods.

Developers are recognising the improved selling proposition a rainwater harvesting system engenders and we’re seeing more and more developments incorporating one of the increasing number on the market. Architects SDA O’Flynn in Cork have recently specified a central collection system for a retirement village in Cork while Gillian Murtagh of Shay Murtagh, suppliers of the Rainman rainwater harvesting systems is completing the installation of 40 self-contained systems in a new estate in Clogherhead. “People realise that water is going to become a commodity no more than refuse and energy.” She says.

The water issue is not simply about supply logistics however. Unprecedented levels of development in floodplains surrounding urban areas have seriously impacted the ground’s ability to deal with water run-off, thereby increasing the threat of flooding. Drainage expert John Knapton says that he doesn’t know a city in the world more aware of the importance SuDS – sustainable drainage systems – than Dublin. These systems are defined by CIRIA as ‘a sequence of management practices and control structures designed to drain surface water in a more sustainable fashion.’

A Rainman rainwater harvesting system for a single house

“There are two fundamental ways of dealing with the water.” Says Knapton. “One is to have all the surfaces permeable, or part of the surface permeable and drain all the water into the permeable parts. Then you put the water straight into the ground. That’s always the most attractive initial thought but often ground conditions prevent you from doing that…So the next thing that people look at is containing the water, detaining it onsite and that’s either going to be in a specially built tank or a more elegant solution is to build a road which will hold the water within the road.” In this instance, instead of traditional solid construction, the road is composed of specially designed materials which contain voids. The entire structure is then surrounded with polythene in order to retain the water. “If there’s a sudden storm, all the water goes into the road and often it’s not just the water falling on the road, but we’ll also take the down-pipes from the housing or the factory or warehouse into the road as well. What we then do is have a very small pipe going out of the road and that limits the water to an amount dictated by the local authority. That’s either two litres per second per hectare or six litres per second per hectare. That’s the simple thing to do; discharge it into the water course at a rate that stops flooding.”

A second option however offers a neat solution both to the water drainage and water resource problem. Recycle it. Formpave is a UK company that manufactures an innovative permeable paving system it calls Aquaflow. Kate Robinson of Formpave explains how it works. “The Formpave SuDS system allows rain to infiltrate through a permeable concrete block paved surface into a stone sub-base where it is cleaned by filtration and microbial action before being released in a controlled manner into sewers or water courses, or infiltrated directly into the sub-grade. The water can also be harvested and used for non-potable purposes such as flushing lavatories and horticultural uses.”

The Formpave permeable paving system was used to solve the drainage problem at Sander's Garden World

Sanders Garden World, a garden centre near Bristol is one of an increasing number of developments where the drainage problem became the solution to the water resource problem. Built on a sub-grade composed largely of peat, with a high water table, the centre had around 14,000 square metres of hard surfacing. The UK Environmental Agency were concerned about the volume of surface run-off and its effect on already overloaded water courses. Using the Formpave system, the water is controlled, cleaned and held in the sub-base, then used to water the plants in the centre. As no run-off leaves the site, this is an entirely self-contained solution. In addition, garden centre staff have found that the water is much kinder to plants than tap water.

In Ireland the Formpave Aquaflow system has been available for the past 7 years and developments here using the system include business & industrial parks, local authority & private housing, schools, supermarkets and recently Áras Chill Dara—the new offices for Kildare County Council and Naas Town Council, where 7,000 m2 were machine laid in the car park, (discussed in more detail in a separate article in this issue of Construct Ireland).

There are now over 700 developments worldwide with Aquaflow installations & Gay McGrath of Roadstone says that a major benefit in using this well proven SuDS system is that valuable land previously set aside for use as attenuation ponds, as part of the planning requirements, can now be utilised as parking areas over the Aquaflow storage system, a major saving in capital expenditure at today’s land prices.

John Knapton, who has worked on several supermarket car-park projects in Ireland says the advantages of permeable paving don’t stop there. “Normally on a road you need to have slopes to drain it, with these permeable ones, the road can be absolutely flat...That’s really beneficial in a supermarket because it’s an awful lot easier to push trolleys on the flat, especially on a windy day…It’s amazing to see these surfaces after rain, because they’re absolutely dry as soon as it stops raining and even during the rain, there are no puddles whatsoever.” In terms of cost, the sustainable solution usually comes out on top. “We often find there’s about a 5% saving from using a permeable SuDS scheme simply because we eliminate the construction of the manholes, the pipes, the gullies and also the falls. Slopes on the road can be tricky to construct.” However, because these systems are so new, local authorities tend to be a little reluctant to adopt permeable roads. “I’ve been looking at this for years and there is no risk but there is a perceived risk that this will be more expensive to maintain. That’s the one thing holding it back at the moment; public bodies fearful of long-term maintenance.” He rejects the suggestion that permeable surfaces need to be replaced sooner than solid roads. “No. We design both permeable and impermeable to last twenty-five years before maintenance.”

So is a self-sufficient site possible? Can all water needs be met without the need for mains connections? To answer the question fully, you need to look at onsite wastewater treatment technologies. Joe Walsh of wastewater treatment company Ash Environmental Technologies spent seven years working in the sector in the US where he witnessed a slow migration away from large-scale sewers towards self-contained onsite solutions. “They were using risk management as the guiding principle behind the whole concept.” Says Walsh. “They found that the risk to the environment was much reduced by treating your wastewater much closer to where it was generated.” By not piping wastewater over greater distances, you are reducing the incidence of leaks due to degradation and storm damage. “There were other benefits too.” Walsh continues. “They were worried about depletion of their aquifers. They were spending a huge amount on groundwater for their drinking water and by sucking it all out and then putting it into rivers, they were causing huge scale depletion of aquifers, so there were benefits in treating it and recharging their aquifers. That’s the way they’ve gone.”

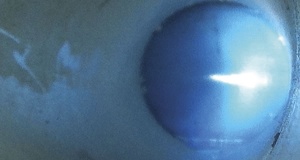

Butler Manufacturing Services has been in the onsite wastewater treatment business for twenty years. “We’re specialists in packaged wastewater treatment.” MD Seamus Butler explains. “Mid range – not single house – the smallest serves four or five houses. The package is a complete, all-in-one road transportable unit. The largest unit fits in a 40ft container for shipping anywhere in the world. We have what the Americans call a plug ‘n’ play unit. It comes in a unitary tank, you connect the pipe in and out, you connect the power to the panel and you switch it on. Raw sewage in one end, treated effluent out the other.” One of the big attractions of solutions like these are that they are eminently scalable. In Lusk in north County Dublin, a 2,000 house development is currently underway despite the fact that the local authority sewer system has yet to reach the site. In the meantime, Butler’s systems will provide the full wastewater solution, and because these units do not require concrete surround, they can be removed and sold on once the sewer system reaches the estate.

Butler Manafacturing Services' BMS BL 4000 Bliver with screen, serving 100 houses at Cullen, Co. Cork

Opinion is divided on the issue of reusing treated effluent. Butler admits the possibility for irrigation or flushing toilets using a secondary plumbing system but has concerns over health. “No matter what treatment it would get, I would still not stand over a system that goes back for potable water.” Frank Cavanagh of Biocycle Wastewater Treatment Systems believes that the treated effluent offers a lot more than conventional irrigation. “Although the effluent has the appearance of water, it contains certain nutrients. It can therefore be used as a subsurface root feeder system, not just for irrigation, but also for the nutrient content. This has a particular application for use in situations such as plant nurseries, which have high water requirements.” Because of the risk of air-borne pathogens when spray systems are used, the subsurface root feeder system is an essential part of the irrigation set up. Moreover, any system must also incorporate sufficient safety features to prevent it from discharging raw sewage.

So with onsite water harvesting and treatment systems this advanced, is a fully self-sufficient site possible? Owen Leonard of Broadstone Engineering believes it is. Almost. “We’d gather all the brown water, treat it in a standard treatment system, then treat it further to bring it to grey water standards and then that could be reused in the house for flushing toilets, washing clothes and gardening, which is about 50% of the household demand.” Any excess can be percolated. If that’s not possible, the effluent has been treated to a high enough standard that it can go into storm water. “That’s the grey water taken care of. Then the potable water in the house, which is for personal hygiene, drinking, cooking and cleaning would be taken care of with the rainwater harvesting and the BEL Rainsafe on a commercial size.” Most of the rainwater harvesting systems on the market restrict themselves to collecting water for things like flushing toilets, washing clothes and irrigation but, Leonard explains, Broadstone’s BEL Rainsafe brings the water to drinking standard. “Rainwater typically goes stagnant when it’s stored.” Says Leonard. “People used rainwater for years and years, for everything in the house but they never really drank it because it was stale. Our system freshens the water, it adds oxygen back into it. Ozone is made in the machine from air and when it’s finished it reverts back to oxygen, so all you’re left with is pure rainwater with oxygen in it.” With this combination – treated wastewater for grey-water use and potable water from the roof – Leonard believes 90% of water needs will be met. For that last ten percent, you’re going to need either a well into the aquifer or a link to the mains. “It’s still a theoretical solution,” he concludes, “but there’s no reason why it can’t be done.”

- Articles

- wastewater

- The SelfSufficient Site

- water supply

- biocycle

- rainwater harvesting

- treatment system

- irrigation

- permeable

- formpave

- SuDS