- Large Buildings

- Posted

Civic Pride

After spending more than two years working in the old fever hospital in Naas, staff at Kildare County Council and Naas Town Council have moved into new headquarters, but it is no ordinary government building. Intended as a landmark not only architecturally, Áras Chill Dara sets an example for large scale sustainable building, as Construct Ireland’s Jason Walsh found out.

Ireland's long boom has seen a massively revived interest in building – it could hardly be otherwise when the entire economy is seemingly grounded in the construction industry, but for all of the building work going on in Ireland, two things are often left as secondary considerations: design quality and sustainability. Located in Naas, County Kildare, the new civic office, Áras Chill Dara, aims to satisfy both criteria.

Built to house Kildare County Council and Naas Town Council, Áras Chill Dara was designed by Heneghan Peng, the Dublin-based architects behind the Grand Museum of Egypt, the Giant's Causeway visitor centre in County Antrim and the proposed redevelopment of Carlisle Pier in Dún Laoghaire.

Both graduates of Harvard Graduate School of Design, the company's founders Róisín Heneghan and Shih-Fu Peng are really only at the beginning of their careers but have already won plaudits for their work. Áras Chill Dara itself has won a Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) European Architecture award in 2006.

Initially based in the United States, upon winning the competition to design Kildare Civic Office in 2001 the pair relocated to Dublin. Heneghan Peng's design beat off stiff competition from other international architects including Irish firm NJB Architects, England's Arthur Collin and Katerina Tsigarida Architects from Greece.

Central to Heneghan Peng's success in winning the competition was not only the building's modern and forward looking design but also its environmental credentials: "The brief aspired toward energy efficient design and green building," says Shih-Fu Peng. "That was the starting point. We needed to employ the best and most innovative techniques to achieve this.

"It [sustainability] was an aspiration and, relative to local government, it is setting an example. Local government set the standard and is on the cutting edge of promoting the standard," he says.

Building for a brighter future

"In a large sense, sustainability can mean nothing," says Shih-Fu Peng. "From a developer's point of view, it can mean the most cost effective solution – sustainable for the developers. In order to really achieve sustainability you need to work with a consultant who belies in true sustainability and who doesn't just apply a fixed set of standards – one needs to look at the building and its purpose. We worked with Buro Happold's Bath office."

In designing Áras Chill Dara, Heneghan Peng saw sustainability as rooted in the building's location: "The nudge toward the forest provides shade in summer, for example.

"From stage one and two, we submitted a building that we felt was strong architecturally but also used its shape to promote sustainability," he says.

Located on a 3.2 hectare site, formerly part of Devoy Barracks, Áras Chill Dara is an 11,500 sq. metre building. The building consists of two blocks or 'bars', each four storeys, that lie on a slightly inclined ground plane, gently rising from the street level which is actually a 'civic garden' public green space. The building's twin bars that form the actual civic offices enclose, and are intended to be a continuation of, the civic garden.

Additionally, the final brief required accommodation for 420 staff, a council chamber, space for Naas Town Council and parking for 413 cars.

Internally, the building's four floors (which total eight across the two blocks) are numbered zero to seven and are navigated by means of a gentle ramp in the atrium which links together the two bars to create a single building. By using this method, not only do able-bodied and disabled users experience the building in the same way, but it promotes the flow of both people and air: "You could roller-blade from the top, the whole way down," laughs Peng. "The ramped space is an open space and every landing is a counter. The staff and visitors move through it, which creates a nexus of interaction."

The qualities of glass as a material which reflects, refracts, absorbs light and changes in degree of transparency relative to the angles of the viewers are celebrated in the building

Vertical loads from the roof are taken by a row of columns along the centre of the space with pre-stressed vertical cables in the façade plane taking asymmetrical roof loads. The ramps hang between the columns and façade cables spanning horizontally. The façade is a rainscreen composed of single glazed sheets and a moderate internal temperature is maintained by sunshades and louvres.

The building has been designed with a relatively narrow cross section of twelve metres while a clear ceiling height of three metres is maintained along the exterior facades.

"Sustainability can be high tech and it can be low tech," says Peng. "The gamut is quite large – it can go from passive to active. Passive would be something like using what you have. Active would be, for example, solar panels."

As it happens, Áras Chill Dara makes extensive use of both active and passive technologies in dealing with two key areas of sustainability – lighting and energy use.

The carpark features 7000 sq.m of permeable paving, consisting of paving blocks which allow surface water to drain through a pollution control filter bed into an underground stone base storage area

For a start, the building makes use of natural light. A glazed curtain wall wraps the entire building, transforming from solid elements to full height glazing according to location. The garden side features an outer skin of frameless glass sheets, screen-printed with a grass motif intended to create a space of entry and shading. According to Hengehen Peng, the qualities of glass as a material which reflects, refracts, absorbs light and 'changes in degree of transparency relative to the angle of the viewers' are celebrated in the building, but there is also a very practical side to the transparent design: "Modern buildings are all glass – if you have more windows, you don't turn the lights on," says Peng.

However, the building's commitment to sustainability goes a lot further than just making use of glass curtain walls.

Engineers Buro Happold designed the mechanical and electrical systems for the building. "It had a brief to be a low energy building," says Edith Blennerhassett, Buro Happold's group director."The key thing about the building is that it has natural ventilation – this is a prime achievement. Most office buildings need to be cooled more than they need to be heated," she says.

"When you are trying to build a low energy building, you need to get involved. Each orientation is treated to reduce solar gain. To the east and west there are three layers of glazing – clear at desk level, above that there is a layer with a prismatic diffuser and above that a more opaque layer."

The heating and cooling of a building is, of course, dictated by the structure itself and some buildings are naturally less susceptible to the climactic conditions than others: "If you walk into a church or mosque it's always cool inside," says Peng. |The whole idea is passive energy – the thick walls moderate the temperature. A tent, however, inside and out will be pretty much the same temperature. A glass building is more like a tent. The challenge for us was to create mass."

Internally, the building's four floors are navigated by means of a gentle ramp in the atrium which links together the two bars to create a single building

The main building bars have an exposed reinforced concrete structure, which plays an active role in the environmental control of the offices. These exposed concrete surfaces help to dampen the temperature swing. As a result, the peak temperature is at around seven PM, at which point it should be virtually empty.

Additionally, the ventilation system is responsive and makes use of motorised windows which open by up to 100 mm at night, allowing cool air to enter the building.

The desire for a natural ventilation system and maximum use of daylight has impacted on the building's design, as Shih-Fu Peng explains: "The building can't be more than twelve to fifteen metres wide, [and] it has to be open plan. It requires a certain way of working – a law firm with many [private] offices may not have sufficient cross ventilation."

The twelve metre width allows for minimal use of artificial lighting, which is, according to Peng, the single largest consumer of electricity in a building. A system was developed with lighting membrane inside the double glazed units to refract daylight onto the ceiling and back onto the work surfaces, allowing for light to be distributed evenly into deep office areas.

When daylight begins to fade, the transition to artificial light, managed by the building's control system, is seamless and the artificial light follows exactly the same path as the natural daylight.

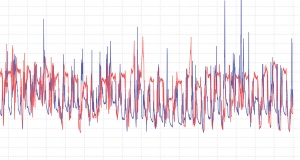

In keeping with the building's combination of high and low technologies, Heneghan Peng performed computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations to ensure that the ventilation would function. CFD is best known as a supercomputing application within fluid mechanics, performed to study the motion of liquids and gasses. Today it is fast becoming a desktop application within the reach of all architects and engineers who need to understand air flow, velocity, temperature and pressure. This high technology and complex computational task ultimately allows for greater use of low impact natural and sustainable strategies in architecture. The narrow cross section is maintained to allow for continuous air flow and the three metre clear ceiling height is provided to redistribute heat build-up.

"Natural ventilation is easier for owner-occupier buildings," says Peng. "The initial cost is a bit higher because you have a management system which opens and closes the windows, but it's a marginal cost and the gap is getting smaller.

"Ireland has a very good climate for natural ventilation, you can't do it everywhere," he says.

In addition to efficient condensing boilers, the building also makes use of solar thermal collectors to heat water and despite Ireland's notoriously cloudy skies, a major reduction in energy costs is expected: "Ireland has up to 37 per cent cloudy days as opposed to Germany with about 31 per cent and Italy with low to mid twenties," says Peng.

"There is a 60 sq. metre thermal solar array generating hot water for the building," says Buro Happold's Edith Blennerhassett. "The expectation is that solar will meet 70 per cent of the building's hot water needs over the course of the year."

The 60 sq. m thermal solar array generates hot water for the building. The expectation is that solar will meet 70 percent of the building's hot water needs over the course of the year

The building's orientation is a factor in use of passive solar energy, shading and solar thermal collection. The garden flows through the site, resulting in an east-west orientation of the major façades. Staff on both sides of the building have sunlight during the day and, in order to accommodate low sun angles, the screen printed glazed screen provides 25 per cent shading on the garden facades. The slot formed between this and the primary building façade constructs a chimney, thereby enhancing the extraction of hot air from within the building. On the other facades, solid panels provide the required shading.

Ireland's climate also brings other potential benefits to a building like Áras Chill Dara: the office makes use of rain water recycling. Water is collected on the roof and in the carpark and is re-used internally in the building.

In order to achieve this, the carpark features 7000 sq. m of permeable paving. The actual system chosen is the Formpave Aquaflow ML storm water source control system, available in Ireland through Roadstone. This system consists of permeable paving blocks which allow surface water to drain through a pollution control filter bed into an underground stone base storage area.

The Aquaflow paving blocks are laid on a 50 mm bed of 5 mm clean washed stone over a special Inbitex geotextile, which filters out any harmful pollutants such as oils, organic matter and heavy metals into the 5mm bed. In time, microbial action within this filter bed breaks down these pollutants, keeping the system clean.

The sub-base stone consists of 250 mm depth of 63-10 mm and 100 mm of 20-5 mm, both produced to a specification which ensures suitable voids for the storage of the storm water. Depending on the permeability of the subgrade the stone bed is laid on a permeable geotextile which allows the retained water to filtrate naturally into the ground. This is called the infiltration system and is the system used in Áras Chill Dara.

Where the permeability of the subgrade is low, an impermeable membrane is used to store the water. The pollution free water can then be released in a controlled manner into the on site drainage system or local river or stream. This is called the tanked system.

The actual storage capacity under the car park in Naas is approximately 150,000 gallons and the ability of this system to filter out harmful pollutants before discharge into rivers has been extensively researched over the past 13 years.

Gay McGrath of Roadstone Dublin Ltd says: "The Aquaflow storm water source control system is the only SuDS system available on the market with scientifically proven pollution control test results. For this reason the system has found favour with local authorities, developers, specifiers and environmental protection agencies worldwide, and with over 700 installations now in place, the results speak for themselves."

Predictably, much has been made of the fact that a government building should be constructed of glass as if this is somehow related to institutional transparency. Shih-Fu Peng quickly disabuses this notion: "There are two things to transparency – if you create a glass building, that's transparent, but it doesn't change how people work. There's also instrumental transparency which is about a methodology of working – it isn't about seeing inside, who cares about that?

"The key driver has more to do with Ireland and 'Better Local Government' than architecture. It's not about glass buildings."

The Better Local Government plan is a strategic policy which has been set out to modernise local administrations across Ireland: "They took a stance – we have to work better – and in order to do that they wanted to create a hybrid organism to put together spacial technology with their own expertise." From there Heneghan Peng and its partners created a building that is sustainable both environmentally and socially.

The twelve metre width allows for minimal use of artificial lighting, which is, according to Peng, the single largest consumer of electricity in a building

Peng explains that, in some respects, the building's impressive façade is less important than its location: "The civic garden is used by the town and was created to display the public space – this is the main elevation, not the glass building.

"In a way, it's an O2 generator – it's green, it creates oxygen and it's a public space," he says.

When it comes to issues of sustainability, much is made of small scale work, after all, smaller projects obviously have less impact on the environment, but Áras Chill Dara demonstrates that grand, large scale and imaginative architecture doesn't have to fall down when it comes to sustainability: "We tend to be strategic and do larger projects," Peng says. "In large projects it's not about creating a grand, iconic identity – that can be good, but that's not what it's about.

"Because we have these large sites they touch the social fabric," he says. "They have the power to transform the space. We see the buildings as a catalyst for transforming and improving the social fabric – that's the goal of [our] architecture."

All photos © Hisao Suzuki, except for solar panel photo, courtesy of Buro Happold

- Articles

- Large Buildings

- Civic Pride

- Áras

- Áras

- chill dara

- environmental design

- kildare

- civic office

- Heneghan Peng

- buro happold

- solar array

- natural ventilation

- aquaflow

Related items

-

Ireland's new central bank hits nZEB & BREEAM outstanding eco rating

Ireland's new central bank hits nZEB & BREEAM outstanding eco rating -

Ground-breaking housing scheme captures one developer’s journey to passive

Ground-breaking housing scheme captures one developer’s journey to passive -

Welsh school fuses passive & eco material innovation

Welsh school fuses passive & eco material innovation -

Kingspan’s Stormont solar array meets unique challenges

Kingspan’s Stormont solar array meets unique challenges -

East London passive school promotes active learning

East London passive school promotes active learning -

Mechanical ventilation and IAQ - what the evidence reveals

Mechanical ventilation and IAQ - what the evidence reveals -

International selection - issue 11

International selection - issue 11 -

Hereford archive chooses passive preservation

Hereford archive chooses passive preservation -

Low energy Tipperary offices go for gold

Low energy Tipperary offices go for gold -

Natural ventilation - does it work?

Natural ventilation - does it work? -

Irish whiskey distillery puts fabric first

Irish whiskey distillery puts fabric first -

Opinion