- New build

- Posted

Handled with care

If thermal comfort is important for people of all ages, it’s even more so for elderly people, for whom the right living conditions can be a matter of life or death. Passive House Plus visited one award-winning extra care facility in Exeter to learn how the decision to go passive was working out for the residents.

Click here for project specs and suppliers

House type: 4,457 m2 care home (53 one and two-bed apartments)

Method: Cavity wall with precast inner leaf. Communal heating and centralised heat recovery ventilation, with dynamically modelled summer comfort.

Location: Exeter

Standard: Passive house classic

Heating costs: £11 to £15 per month (indicative space heating costs for a one-bed and two-bed apartment*)

* see ‘In detail’ panel for more information.

As you arrive at the new Edwards Court Extra Care housing scheme in Exeter, the entrance is understated, austere even. Go through the doors though, and you enter a surprising, lovely space. The foyer is high and airy , with double- height glazing looking out onto a garden. Above, a gallery is set into a wall richly decorated with natural wood fluting. People are sitting chatting and playing scrabble, watching the world go by.

Beyond the entrance, the corridors are naturally lit, some with views over the gardens or towards the river. You pass through daylit corridors, some with views over the river Exe, and more attractive communal spaces, again decorated with an abundance of solid natural wood and colourful furnishings. The building is peaceful and fresh, and with a goldilocks sort of temperature: not too warm, not too cool, and perfectly even.

What is probably loveliest of all about this apartment building though is the fact that it is council-owned and run. It is not a highend, eye-wateringly-priced private sector facility. The residents, who are mainly over 55, with low to moderate care needs, pay ‘affordable rent’ to live there.

The quality of the building is really appreciated by residents – and by their families. “When people come in it’s absolutely ‘wow!’” one resident told Passive House Plus. “When my sister-in-law and our niece came to stay, they were really surprised at how nice it is – they said ‘Ooh, it looks like a hotel!’”

Design for users

This article was originally published in issue 46 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

Edwards Court is in many ways quite different from a hotel, however. Most hotels feature long, straight, gloomy corridors, some enhanced with a hint of stale carpet. Edwards Court has none of that.

A hotel is built for privacy – however, Edwards Court is very much built for community too. To this end it cleverly borrows from the towns and villages of the outside world.

You have the chance to be among people even when not actively seeking company, and you can see what’s going on and who is around. If you want to socialise, there are places to meet for chat or a coffee, or to eat together.

This connectedness is achieved by a porous layout. Window and galleries like the one above the entrance foyer give views down from corridors into communal spaces. On the roof is a cafe serving snacks and hot meals, and the popular roof terrace has views over the leafy riverside to the hills beyond. Individual apartments can be fully private, or residents can peek out slantways from their kitchen windows down the corridor. Once out of the door, each flat has a built in seat (that some residents have personalised with ornaments).

The client team at Exeter – in particular, Exeter’s asset management lead Gary Stenning, and Emma Osmundsen, the then MD of Exeter City Living – visited similar facilities elsewhere to learn what residents did and didn’t like. Then working with Lee Fordham, Kirk Rushby and colleagues at Architype they developed this very effective design.

Residents are full of praise for the facility. As one resident, Adrian, explained: “Before, we were in a flat supposedly for over 55’s, but my wife has increasing mobility problems and early dementia, and she was really struggling, even with a stair lift. She was very low, feeling like her life was over.

“Here everything is level access and with her wheelchair she can get everywhere in the building, and go out. She is so much better here, she settled in really quickly.” Adrian is active in the community that is forming here – with chat sessions, board games afternoons, plus a weekly music evening that he organises.

Visible, tangible luxury

It’s unbelievable. My mother’s only been here a few weeks and the change in her is incredible. This is a miracle place!

Adrian’s appreciation of the building is shared by his fellow residents, Claire Taylor, the housing manager says: “Everyone finds the building light, bright and decorated in a very pleasing manner. They love the terrace upstairs and the view.”

The generous design and quality finishes were not imposed by architects spending their client’s money unasked. The luxury was absolutely central to the brief. “Exeter were very keen to drive the quality so it was the same as a private sector facility,” architect Kirk Rushby explains. If anything, Edwards Court is not only as good as most private sector facilities: compared to those Passive House Plus has encountered, it is rather nicer.

In the individual flats, the thoughtful layout and beautiful finishes continue. The ceramic tiled floors give off a gentle, even heat in winter. Every flat is well daylit and has a balcony big enough to sit out on, plus room for some pots. The balconies are all angled to catch the sun for at least half the day. But the luxury at Edwards Court is not only the things you can see, as the residents appreciate.

“The flat is really comfortable, we have thermostats to control the temperature, and can open the windows or the door to the balcony when it’s warm,” Adrian says. “We just wear short sleeves all year round, but it doesn’t seem to get too hot.”

He explained how his disabled wife has benefited: “We have underfloor heating which is great. My wife gets up often in the night, so it is lovely that it stays warm all night too.” You could say the comfort in the building is distinguished by what you don’t notice: no cold or drafty places where you wouldn’t want to sit, no oppressive heat in summer – and no smells.

Even at lunchtime, the only noticeable smell is the faint linseed-y presence of the marmoleum underfoot in the circulation spaces. “The air is always so fresh, you can’t smell any cooking, even from the café,” Adrian says.

Claire Taylor is experienced with care facilities and is used to residents being too cold or too hot. But not here: she has had not one complaint about indoor temperatures.

“We have an age range from 50 to 101 and to never get, even in the depth of winter, any comments about the heating is a major compliment.”

A safer environment

As we know, the older we get, the more sensitive to cold (and excess heat) we become. For those of us with mobility or cognition problems – like many residents in Edwards Court – this vulnerability increases. As experienced passive house clients, Exeter City Council were well aware of the benefits passive house would bring to this occupant group.

The goldilocks conditions inside – not too warm, and not too cold – are not only very nice to live in: they keep the occupants safe, and aligned with the kinds of temperatures required by EN16798-1, a standard which sets indoor environmental quality requirements for energy calculation methodologies.

“We had in our minds that passive house would deliver thermal comfort and fresh air, with extraction where we need it. We are very pleased with the result,” Gary Stenning says. The comfort makes life a great deal easier for the housing manager. “Age Concern recommends 21 C temperature for extra care provision,” says Claire Taylor. “People need to be warm, but if it is much warmer than 21 then you can start to risk issues with dehydration and stroke. We check the temperatures to make sure the flats don’t get too much warmer than this, and I haven’t seen any flats go above 21, winter or summer.”

Gary Stenning confirms this was the intention: “The hope was that in winter, with the warm surfaces including the windows, and lack of drafts, people would not feel the need to turn the heating up high. This seems to be what is happening.”

Older people are also more vulnerable to infections – not least, to airborne infections such as covid. Research has shown that the lower the air exchange rates in a building, the more outbreaks of respiratory infection you will have. The centralised passive house heat recovery ventilation here delivers a steady stream of pre-warmed air to a set target, without so much as a hum, never mind a draft.

As Hugh Griffiths of E3 Consulting Engineers explains, the units chosen were from Swegon’s Gold range. “Plate Heat exchangers for the kitchen, rotary wheels for the general areas, chosen because they are passive house certified and because we have used them on previous passive house projects,” he says. While the systems have no recirculation outside of the air handling units themselves, in the case of the rotary wheels Griffiths says there can be a very small percentage of recirculation.

How the passive house standard was met

Killian Edwards Court contains 50 small flats, plus communal, office and circulation space, over four storeys. With a building this size, achieving passive house levels of thermal efficiency should not be challenging. The team opted for a layout with apartments on both sides of a central – albeit daylit – circulation spine. This gives an excellent form factor (surface area to volume ratio) of 1.5. As a result Architype were able to specify a standard 150 mm cavity construction – cheaper and more straightforward than a thicker build-up.

The spec at Edwards Court includes a brick outer leaf, 150 mm cavity with Isover mineral wool fill and thermally broken TeploTie wall ties, albeit with a comparatively modest U-value for a passive house of 0.249 enabled by the building’s form factor, and the forgiving Exeter climate. Where most cavity walls have a masonry inner leaf the inner frame is pre-cast concrete, a decision that helped the building’s airtightness, albeit at an embodied carbon cost. Precast concrete tends to have high embodied carbon, given the typical spec of high cement content and steel reinforcement used for precast concrete. Early on, Architype explored the option of reducing the embodied carbon of the concrete via substituting cement for ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS), a low carbon byproduct of the steel smelting process.

“We started with a high GGBS specification for the concrete but this was removed due to the availability of GGBS due to high market demand,” says Kirk Rushby. “We were also therefore concerned about the actual sustainability of this.” The embodied carbon of the building wasn’t calculated, Rushby explains, because although Architype had helped develop Eccolab, a design tool which calculates embodied carbon, staff hadn’t been trained in the use of the tool when this project was at design stage.

-

Installation of EPS insulation below slab

Installation of EPS insulation below slab

Installation of EPS insulation below slab

Installation of EPS insulation below slab

-

Foamglas installation below structural walls

Foamglas installation below structural walls

Foamglas installation below structural walls

Foamglas installation below structural walls

-

Tight insulation cut to soil stack penetration

Tight insulation cut to soil stack penetration

Tight insulation cut to soil stack penetration

Tight insulation cut to soil stack penetration

-

Edge of ground slab revealed after formwork removed

Edge of ground slab revealed after formwork removed

Edge of ground slab revealed after formwork removed

Edge of ground slab revealed after formwork removed

-

Aerial shot of the precast concrete frame erection

Aerial shot of the precast concrete frame erection

Aerial shot of the precast concrete frame erection

Aerial shot of the precast concrete frame erection

-

A dedicated mitre jig setup on site to cut EPS plinth insulation

A dedicated mitre jig setup on site to cut EPS plinth insulation

A dedicated mitre jig setup on site to cut EPS plinth insulation

A dedicated mitre jig setup on site to cut EPS plinth insulation

-

Neat and tidy plinth insulation install to the building perimeter

Neat and tidy plinth insulation install to the building perimeter

Neat and tidy plinth insulation install to the building perimeter

Neat and tidy plinth insulation install to the building perimeter

-

Weathertight seal between windows and concrete frame

Weathertight seal between windows and concrete frame

Weathertight seal between windows and concrete frame

Weathertight seal between windows and concrete frame

-

Quality control of the mineral wool cavity insulation with TeploTie basalt wall ties;

Quality control of the mineral wool cavity insulation with TeploTie basalt wall ties;

Quality control of the mineral wool cavity insulation with TeploTie basalt wall ties;

Quality control of the mineral wool cavity insulation with TeploTie basalt wall ties;

-

Excellent weatherproofing around the penetrations for the air handling unit

Excellent weatherproofing around the penetrations for the air handling unit

Excellent weatherproofing around the penetrations for the air handling unit

Excellent weatherproofing around the penetrations for the air handling unit

To offer the depth of reveals needed for controlling summer solar gains, the windows and doors are not set in the line of the insulation, but rest on the inner concrete frame, with the insulation line kept continuous by the addition of a Compacfoam “frame round the frame” overlapping the cavity insulation. “This was fiddlier to design, but actually, it was easier to build, as the weight of the doors and windows sits over the structure,” Kirk Rushby explained.

To avoid thermal bridging, balconies are self-supporting vertically, but still have to be tied in to the wall behind for horizontal stability. The ties had to be carefully designed to ensure there was no thermal bridge back into the building. And of course every balcony has a door, requiring a robust threshold (that can take feet and mobility aids).

As Kirk Rushby put it: “The inclusion of balconies immediately means 50 extra doorways. And you need to find a way to support them that does not form a thermal bridge. In passive house, balconies are a nuisance technically, but they were absolutely essential. The whole country learned this during lockdown – there was no question we would not include them. You can see from the way people use them that they are well worthwhile.

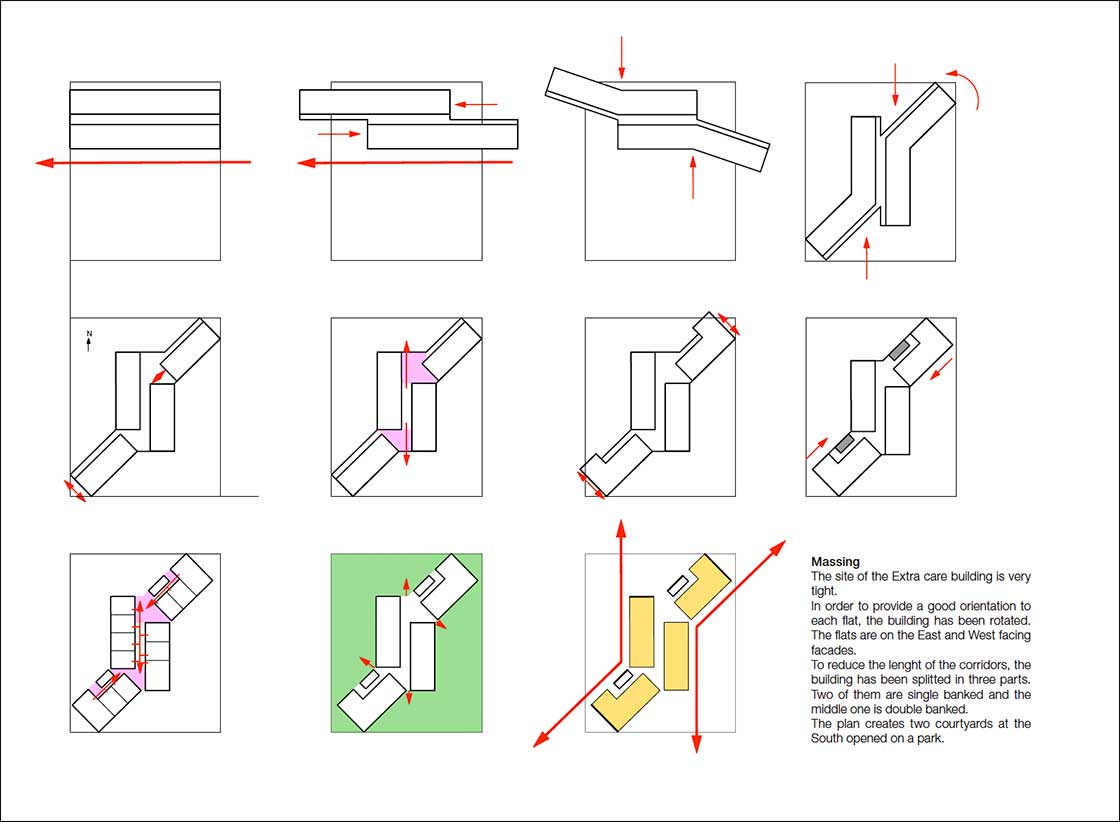

With such a good form factor, passive house heat demand could be met without the need for a south orientation. This was a great advantage, as to give equal access to sunshine for occupants on either side of the building, an east-west orientation worked a lot better – and fitted better with the shape of the site. The alternative would have been two narrow wings of apartments, but this would have been an inefficient shape with a much bigger envelope, all needing a higher fabric specification, greatly pushing up the construction cost.

Of more concern perhaps was controlling overheating. “You do need to take care to control gains, with the lower morning and afternoon sun, so we paid a lot of attention to the glazing design. We were careful not to over-glaze, sizing the windows so they were well shaded by the reveals.

Chamfered inner reveals both increase the daylight indoors, and enable more effective ventilation even with window restrictors. The opening windows in the corridors are also useful in summer, Claire Taylor adds.

It was important to control internal gains from services – both to limit overheating, and to meet the passive house primary energy targets – not least because at the time of the design, back in 2017, the standard low cost choice for heating was gas. Gas has a high impact on the primary energy totals compared to heat pumps, in spite of the fact that gas has a lower primary energy score than grid electricity. The reason: fossil fuel boilers are less than 100 per cent efficient, whereas heat pumps are typically 300 per cent efficient or more.

Why was a fossil fuel source chosen for the project? “The project has been in the working for a long time and the design information for the project was being developed in 2015,” says Kirk Rushby. “At this time, we were encouraging clients to focus more on reducing demand rather than spending on any form of renewable. If we were to look at this today we would certainly take a different view, especially considering how appropriate a heat pump would be with a low temperature underfloor heating system.”

Communal hot water circulates at 60 C to avoid legionella risk to such a vulnerable population. But the circulation is confined to short loops that do not enter the apartments. Separate small-bore spurs supply the shower, washbasin and kitchen to minimise losses into the occupied spaces. The communal underfloor heating circuit meanwhile runs at around 30 C, so again losses are very low. Overheating risk was checked by IES dynamic thermal modelling as well as in PHPP.

For a larger building, mechanical and electrical engineer Hugh Griffiths of E3 explains that dynamic modelling is recommended, to understand temperatures in individual spaces and across the day. Minimal overheating was predicted.

Following Exeter’s well-established requirements, indoor conditions were also modelled for predicted climate in 2050 and 2080. This did point to a future overheating risk, so the building was future proofed accordingly. Rather than spend money adding shading and space cooling now, when it is not necessary, provision has been made to retrofit external shutters if and when the need arises. Ventilation ducts were pre-insulated to allow for cooling, on the basis that taking down the ceilings to retrofit insulation later would be a horrible job.

Certification

People need to be warm, but if it is much warmer than 21 then you can start to risk issues with dehydration and stroke. We check the temperatures, and I haven’t seen any flats go above 21, winter or summer

Mike Roe at Warm was the certifier, and found the project commendably straightforward to take through the requirements for passive house.

“It was not that different in the end from a standard apartment block. The differences were that the apartments are very small, so there is a high density in terms of equipment. At that time PHPP was not as flexible about primary energy in relation to occupant density as it is now. The primary energy target was quite challenging to meet but we just got through, helped by the clever services design which really minimised the energy loads.

While the project may have navigated the rarefied space of passive house and PHPP calculation, how would it fare when put through the UK’s national methodology, SAP? Curiously, the apartments received relatively poor Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) scores of C and in once case B. Kirk Rushby says this is due to the way that EPCs are calculated. “Each apartment is assessed as a separate unit with a nominal U-value given to party walls. Essentially it doesn’t account for the efficiency of a large block of apartments huddled together.”

Passive house in Exeter

Edwards Court is another fine feather in Exeter’s cap, adding to the already excellent reputation of passive house in the city. Adrian said his daughter uses the pool at St Sidwells, “which is also passive”.

“She finds it really nice at the leisure centre, and she said to us ‘if your new flat is passive it should be good’.”

The considerate management and care provisions, the occupant-centred layout, and the gorgeous fit-out of the building, combined with its unobtrusive comfort, have worked wonders for some occupants. The son of another resident told Passive House Plus that his mother’s wellbeing had transformed since she had moved in. “It’s unbelievable. She’s only been here a few weeks and the change in her is incredible. This is a miracle place!”

Selected project details

Client: Exeter City Council

Architect: Architype Ltd

M&E engineer: E3CE

Civil/structural engineer: Price & Myers

Energy consultant: Elemental Solutions

Project management/quantity surveyors: Arcadis

Main contractor: Kier Construction Ltd

Mechanical and electrical contractor: Whitehead

Passive house certifier: Warm

Windows and doors: Ecowin

Roof lights: Lamilux

Entrance doors: Raico

Wall insulation: Isover

Thermally broken wall ties: Ancon

Thermal blocks: Foamglas

Roof insulation: Bauder

Floor insulation: Foamglas

Floor insulation: Styrene

Airtightness products: Pro Clima

Bricks: Ibstock

Timber flooring: Junckers

Floor tiles: British Ceramitile

Linoleum: Forbo

Mechanical ventilation supplier: Swegon

In detail

The UK’s first and only passive house extra care apartments. Exeter City Council’s innovative new Edwards Court Extra Care scheme provides 53 one and two-bedroom mixed tenure apartments. Designed to encourage community and companionship among its residents and neighbours, a variety of communal areas are interspersed throughout the building, on the rooftop, and in the garden walkways and terraces.

With in-depth research into dementia support and new design thinking, Architype has created a healthy, homely and sociable environment where residents can safely maintain an independent lifestyle with various levels of support and care. Designed specifically to address the mental and physical needs of an older demographic, these welcoming ‘homes for life’ encourage movement and social inclusion, helping relieve demands on the NHS.

To meet Exeter City Council’s demanding sustainability and health and wellbeing standards, the passive house design helps address fuel poverty by radically cutting heating bills and is climate-proofed to 2080.

Building type: A 4,457 m2 care home including 53 one and two-bedroom mixed tenure apartments.

Site type & location: Suburban brownfield site on the edge of Exeter City.

Completion date: September 2021

Budget: Final account figure approx £12m.

Passive house certification: Certified passive house classic

Space heating demand: 13 kWh/m2/yr

Heat load: 9 W/m2v

Primary energy non-renewable: 133 kWh/m2/yr

Heat loss form factor: 1.47

Overheating: IES modelling 0.5-1% using current weather data

Number of occupants: 80

Airtightness (at 50 Pascals): 0.23 ACH

Energy performance certificate (EPC): Each apartment has a separate figure but all apartments achieved a C rating between 76-79 with one exception of B (83)

Embodied carbon: Embodied carbon analysis not undertaken

Measured energy consumption: Not yet available

Thermal bridging: With a large building and therefore better form factor the attempt was to make the building form efficient enough that a typical insulation of 150 mm thick masonry cavity fill generally could be used that would be similar to a more standard construction. Initially design loads allowed a raft slab on top of pile-caps by designing the structure to spread across load-bearing walls rather than having point loads. Additional loads from the precast frame manufacturer meant that this could not be achieved, but Foamglas could be used below walls to take the loads with an EPS infill which still made a thermally bridge-free construction. Parapets were reduced to a minimum but required to terraces and plant areas. These were thermally broken with a break designed by the concrete frame subcontractor similar to a Schoeck type. Balconies were kept structurally separate from the building with ties back to remove thermal bridges and lime mortar with bed joint reinforcement was used to allow the five storeys of brick to be self-supporting, thereby removing the need for structural shelf brackets.

Heating costs: Calculated costs for typical apartments of £11 to £15 per month, based on a 45 m2 one-bed apartment, and a 62 m2 two bed apartment. This is based on a number of assumptions. First, it’s assumed that each apartment has the same space heating demand (13kWh/m2/yr) of the whole building, when the reality is that some will be above or below this figure. Secondly, it’s assumed that that the boiler will be delivering heat in line with the stated gross seasonal efficiency of 96.5 per cent. Thirdly, a high unit price for communal gas of 22p is assumed, based on an article from The Guardian on gas price spikes, “UK households with communal heating facing 350% rise in energy costs.” If we instead focus on the whole 4,457 m2 building, the calculated space heating total is £1,100/month – for 53 flats and all common areas.

Ground floor: 65 mm bonded screed with underfloor heating with VCL, on 25 mm rigid insulation, on 300 mm reinforced concrete slab, on 100 mm of EPS insulation with Foamglas in load bearing areas. Concrete slab acting as airtight layer. U-value: 0.206 W/m2K

Walls: 100 mm brick tied back with TeploTie thermally broken wall ties, 150 mm full fill Isover CWS 34 glass mineral wool slabs, 200 mm precast concrete walls with service zone and plasterboard. Precast concrete with external joints sealed with Pro Clima Aerosana Viscon liquid sealant. U-value: 0.249 W/m2K

Roof: Bauder bituminous warm roof system with waterproof layer, 160 mm PIR insulation and VCL on 150 mm precast concrete planks. VCL acting as airtightness layer. U-value: 0.131 W/m2K Windows & external doors: Zylefenster windows by Ecowin, triple glazed aluclad timber windows. Average Uw-value: 0.84-0.88 Wm2K. G-value: 0.48

Roof windows: Lamilux FEEnergysave triple glazed roof lights

Heating system: Two Potterton Sirius 3 90kW gas boilers with a gross seasonal efficiency of 96.5 per cent distributing through underfloor heating embedded in the screed. Ventilation: Four centralised ventilation units, as follows:

North flats and communal areas: Swegon Gold F RX (Size 14): Temp efficiency: 86 per cent

South flats and communal areas: Swegon Gold F RX (Size 12) Top: Temp efficiency: 85 per cent

Fourth floor communal areas: Swegon Gold F RX (Size 07): Temp efficiency: 84 per cent

Kitchen: Swegon Gold F PX (Size 07): Temp efficiency: 76 per cent

Water: Low flow fittings as per AECB Water Standards

Electricity: No renewables on site

Sustainable materials: A priority for Exeter City Council, the building aligns with the Building Biology Association’s 25 Guiding Principles of Building Biology for a healthy, beautiful and sustainable building in an ecologically sound and socially connected community.

It reduces physical, chemical and biological risks and eliminates toxic materials and electro-magnetic radiation. Materials are as natural as possible, with particular care made to avoid skin irritants and ensure optimum air quality. Paints are natural and timber is lacquered rather than oiled to reduce VOCs (Volatile Organic Compounds) which are hazardous to human health. To keep dust and particulate matter levels low, surfaces that more easily collect duct such as carpets have been avoided. Fibre insulation has been selected on the basis of having the lowest formaldehyde content possible. Cellulose insulation to top floor terrace area. Natural finishes such as oiled timber floors, linoleum, timber ceiling and wall finishes, low VOC paints and ceramic tiles.

Image gallery