Label Conscious

In this special feature, Construct Ireland draws from the views, hopes and concerns of four people ideally poised to comment on the implications this directive will have on how we design, construct, renovate, manage and think about buildings in Ireland.The construction and property industries in Ireland are faced with an unprecedented challenge over the next few years as the EU Directive on the Energy Performance of Buildings comes into effect.

This landmark directive will require that energy labels must be granted and made available to prospective owners or tenants for virtually every type of building, and is anticipated to become a key factor influencing the value, and thus the saleability of property in Ireland.

The Engineer's View

By Patrick Stephens , Chairman of the Association of Energy Professionals of Ireland (AEPI)

On the 4th of January, 2006 the EU Directive on the Energy Performance of Buildings will be made law in Ireland. Like Christmas, it may seem like a very long time away but the implications of the new directive will be profound. One can’t help but worry, considering our handling of the well-flagged “waste problem”. Living here among the forty shades of green, making a note to attend the various court dates and finding illegal dumps up and down the eastern seaboard, one might be forgiven for thinking we were living in an episode of the Simpsons.

Let’s face it, when it comes to implementing and observing environmental legislation we are a lazy lot! So what’s the big deal about another law from Europe? The latest EU parliamentary elections have shown that many people are fairly ambivalent about the EU and some feel we are already over regulated. This ambivalence to the many advantages that membership of the EU has brought to us (economic, environmental, health & safety, infrastructural and so on), and a dislike for regulation are two of several real barriers to the full and timely implementation of the new directive. But I am getting ahead of myself. First let’s look at the directive and the many benefits that Ireland stands to receive.

The directive, widely known as the “Energy Performance of Buildings Directive” (EPBD) was published in the EU Journal on 4 th of January 2003, and will be transposed into Irish law on 4 th of January 2006. There may be an extension available to 4 th of January 2009, for countries that are unable to implement the directive due to a lack of technical ability (such as qualified surveyors), but I’m sure that won’t happen!

The EPBD will enable building purchasers and leaseholders to clearly establish the energy efficiency of the building they are interested in. What method will be used to inform people has yet to be finalised, but it will almost certainly look like the present energy labelling system used extensively for electrical appliances. The electrical appliance labelling system has been very well received by the public with clear identification of its purpose and meaning. Most appliance manufacturers are now set up to make only “B” or “A” standard white goods. Indeed because of its success there are talks of introducing an “A+” label. Have you ever wondered why you get so much information in the box when you buy a kettle, but nothing at all when you buy a house?

Well, from 4 th of January, 2006 if you’re going to spend €300,000 (and 25 years of your life’s earnings) on a house, it would be good to know if you’re getting an “A” rated house or not. Buildings in the commercial and public sector over 1,000 m 2 must also carry an energy label, irrespective of whether they are on the market or not. Indeed all public buildings must display the energy label in a prominent position for members of the public to see. The labels will be valid for a maximum of 10 years but a new label must be issued if the building has been subjected to any major renovations. Presumably those who have refurbished their buildings will want to get a new label and advertise their improved energy efficiency and environmental awareness.

The building label will of course be a lot more sophisticated than just a letter on a scale. The EPBD labels must also come with advice on how to make your building more energy efficient. There will also be strict regulation on the performance of boilers and air-conditioning equipment. Boilers over 20 kW using non-renewable fossil fuels must be inspected “regularly”. Boilers greater than 100 kW must be inspected every 2 years if using oil or solid fuel, and every 4 years if using gas. These inspections will not place any additional burden on most buildings since insurance companies seek these inspections now anyway. Every heating system over 20 kW and over 15 years old must be completely inspected, and advice given on appropriate upgrade, or replacement. Air-conditioning units over 12 kW must be inspected “regularly” and advice given on energy efficient operation, replacement and so on.

The EU has been motivated to bring this directive forward because 40% of all energy use in Europe goes into buildings. Think about that for a minute. Almost half of all the energy consumed in Europe is used in buildings for the basic requirements of light, heat and power. Most people believe that there are several, very large industrial plants consuming vast amounts of energy, somewhere. It is difficult for us to accept that we are using the energy, and the inefficiencies are in our buildings.

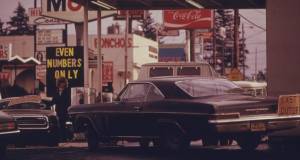

Security of energy supply is another important driver at EU level. For the past six months everybody on the planet must have become aware of the increasing importance of “energy politics”. For Ireland (a country that imports over 90% of energy requirements), the issue of security of supply has never been more important. We are proud of our economic development in the past 10 years. Without a sufficient energy supply, economic activity will come to a stop. Only those who witnessed the petrol queues and rationing of the late 1970’s can comprehend the total dependence of our society on oil. This dependence on fossil fuels for building heating and hot water is certain to continue for many years, especially in urban areas. As a growing economy we have to increase the “productivity” of our buildings. In a way you could think of the EPBD as “benchmarking” for buildings.

Consider that in Ireland some 800,000 houses were built before the introduction of the Building Regulations in 1980. The energy consumption in these buildings varies greatly from 200 to 800 kWh / m 2 / year. Most houses built today (that comply with the building regulations) will consume less than 90 kWh / m 2 / year. Comparing these efficiencies you can see that a lot of older housing stock has a lot of improving to do.

The other great driver and benefit from more energy efficient buildings is a better environment. A simple measure like the abolition of bitumous coal prompted many to re-evaluate their heating system, and install cleaner more efficient heat generation equipment. The EPBD will have the effect of also prompting building owners to improve the energy efficiency of their buildings, reducing the financial burden on the occupants and the environmental emissions for all of us.

The Kyoto protocol has an assessment date of 2008 – 2012, to show “significant progress” on meeting our commitments. The EU target looks likely to be met, but Ireland’s contribution is sadly lacking. Our commitment was to limit the increase of emission to 12% over 1990 levels. Today we stand closer to 35% over 1990 levels. Measures like the EPBD are an important part of demonstrating our commitment to international agreements.

The time scale for implementing this new directive is very short. The directive’s impact on the building industry for architects, engineers, developers, builders, purchasers, owners and managers will be profound. It is important that all of the key players are well informed about the forthcoming directive, its ease of use and its importance for economic and environmental reasons.

In order to implement the directive on time it is important that sufficient surveyors are trained and the methodology for conducting the surveys is standardised and agreed. A lot of work has already been done, and is being done at EU and national level. Sustainable Energy Ireland (SEI) is the agency charged with the onerous task of informing the public and addressing the need for skilled surveyors. The Association of Energy Professional in Ireland (AEPI) is also very concerned that the EPBD will not be delayed because of a lack of suitably qualified surveyors. The AEPI was set up two years ago with the express aim of promoting the work of its members working in the fields of energy generation and demand side management. We have many members who are already well qualified to perform the required surveys, as soon as the methodology has been finalised.

The day of finally getting that “user manual” with your building is getting closer. Soon the buyer or building occupant will know what the going energy costs and environmental emissions associated with their building are. This is important information for the most important purchase most people will ever make. The sooner we know the better.

The Architects View

The Architects council of Europe (ACE) is the professional representative body of the architect’s profession for all 25 Member States in the European Union, representing around 450,000 practising architects. The ACE lobbies for the interests of the profession and for society at large regarding the quality of the built environment, in front of the EU commission, parliament and, where possible, through national organisations with the Council. The main work of the ACE is carried out by Taskforces, and the Taskforce working on the EU Directive on the Energy Performance of Buildings is the Taskforce on Environment and Sustainable Architecture. Jeff Colley speaks to Adrian Joyce, architect, Senior Adviser with the ACE in Brussels about the views of the ACE on this groundbreaking development.

How does the ACE feel this directive should be approached?

Firstly the ACE believes that the directive is long overdue; this is a measure that could have been taken a long time ago and is one that should now be implemented as soon as possible. The ACE feels strongly that any directive like this should not be prescriptive in its approach and that any standards or formats that it lays down should be performance based. Targets should be performance based in order to allow the architect or designer to interpret them in a creative way. The ACE sees this as an important horizontal issue. For example, it is better to set a target for energy consumption such as 50kw per m2 per year rather than to limit the permissible glazed area in a building to, say, 20% of the external wall area.

Does the ACE believe that the directive will have a big effect on how buildings are designed, maintained and renovated?

Yes, the biggest impact expected in the medium term, say 5 years, is regarding the marketability of properties with poor ratings – they may not be marketable at all. It is possible that the market value will disappear from buildings that don’t have good energy performance. Of course, that’s the main objective of the directive – to mobilise market forces to improve energy performance in buildings.

It strikes me as a glass half full approach, more so than previous measures such as increases in thermal requirements under Part L of the building regulations. Hopefully it should lead to a situation where consumers are going to be looking for their buildings to achieve more?

A building that doesn’t have a good certificate won’t be popular. Maybe it’s not so much the buyers and sellers and leaseholders that will be most interested in this directive, but the financial institutes who, certainly in a country like Ireland where they own 80% of the commercial property, will look for buildings to have a good rating before they invest. This raises several interesting questions including the following:

- Is this going to lead to a large quantity of building stock becoming undesirable, and therefore to potential dereliction of a certain type of building or areas of a city?

- If the will to upgrade and invest doesn’t manifest itself, are these buildings going to become obsolete, leading to demolition requirements and wasteful use of the resources that are embedded in the building?

It quickly builds into a complex issue and to the fact that, in the short term, there is a risk that there could be a certain category of building in the commercial sector that could become un-sellable, leading to a reduction of supply of commercial space.

Does the directive not provide some form of protection here in terms of recommending alterations?

When an architect visits a building and sees it won’t reach the desirable certificate level they can make recommendations about physical improvements, such as over-cladding, changing the glazing, or improving the mechanical ventilation systems. These are real architectural elements that open a door to a lot of work for architects, if it is properly exploited. We make this message clear across Europe because the directive applies to all climatic zones.

Based on the risks you’ve identified, should there be other incentives in place?

The view of the ACE is that the Energy Performance Directive is just one step to a future situation where there will be a “Building Passport”. This concept first emerged from the work of an expert group of the Commission managed and chaired by the ACE on the topic of Sustainable Construction Methods and Techniques in 2003. Such a Passport would not only take energy performance into account, but a wider range of sustainable measures such as the environmental, economic and social impact of the building and the embodied energy of the building. The ACE is looking at how a wider certification process could be introduced over time.

How should the ratings be carried out in order to have most effect?

There is no question that the rating should be based on actual energy consumption rather than projected, simulated energy consumption. Unfortunately there is evidence that the simulation of a building’s energy performance at the design stage is not easily translated into the predicted performance in reality. This arises, firstly, because of the difficulty to enforce the kind of standards that have been put in place to date, and, secondly, because of the difficulty of implementing in 3 dimensions what is usually drawn in 2 dimensions. Features such as insulation around windows, junctions of roofs and walls are difficult to translate into the actual physical fabric of a building. So you tend to get a lot of heat holes where heat just rushes out of the building.

The ACE would prefer to see that if a building is given a certificate based on a simulation or a calculation from the design stage, that that certificate is checked against real consumption figures, say, 2 years after it is built – not 5 years as required by the directive. There is no point in reflecting simulations – it is necessary to reflect reality.

Is it possible that energy ratings may be misinterpreted as green or eco labels for buildings, and is this a concern?

There is a potential for that confusion to arise. An eco or green label would have to go further than just energy consumption and this directive only requires an energy consumption label and it should be marketed and understood as such, in the same way that such labels are found on dishwashers or washing machines. It’s a good first step but it is desirable to get beyond this to other issues such as water consumption, lifetime costs of the materials, lifetime costs of the building and environmental and social impact indicators that could be a “passport” for the building.

Taking on from the examples that we’re seeing with the likes of energy labels for room air conditioners, where the labels were graded from A to G, and the intention of the European Union in this process is to introduce mandatory minimum ratings in these areas. It’s been suggested that units that achieve a G rating will be banned for sale in 2004 and F rated units banned from the end of 2006. Do you think similar sort of measures will occur with buildings?

Certainly, and that’s the expectation of the ACE, as energy issues shouldn’t be add-ons to a building; they become integral to the concept behind the design of the building from day one. It’s integrated thinking like this that the ACE promotes.

Regarding other issues such as air quality, could this directive have negative impacts?

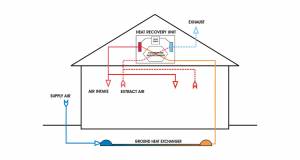

That remains to be seen. Any person making recommendations about upgrading a building must be aware of the consequences of those recommendations. For example if it is recommended to tighten up the envelope of the building there must also be recommendations appropriate to the ventilation systems with, say, heat recovery so as not to detrimentally affect or worsen the existing conditions in the buildings.

This is a key reason we need to have professionals in the industry pushing this directive rather than people with more vested interests in certain technologies.

It seems to the ACE that the task of certifying cannot be relegated to a purely technical task of adding up electricity or gas bills and coming up with a figure. It needs to be a more holistic view of the building as a system. There is no doubt that professionals should be the ones doing this work. Another interesting angle that has been raised by the Chair of the ACE Taskforce is whether or not the Member States will react to this directive by setting minimum targets for the energy performance of buildings, and how that would be transposed into national law. There might be an interesting patchwork that builds up in Europe over the next five to ten years that could teach us valuable lessons in a relatively short time frame.

The Researcher's View

Jay Stuart , Director of EcoCo, sustainable building consultants, became familiar with the directive through his involvement in the Europrosper research project while working for the Energy Research Group at UCD. Europrosper’s objective is “ to improve the energy performance of existing buildings, specifically in the office sector, across the EU by the process of energy audit, benchmarking and certification”. Jeff Colley spoke to Stuart, to learn his thoughts on the directive.

What is Europrosper?

Europrosper is a project that was conceived before the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) was drafted. We knew of the concept but none of the details. Nonetheless the labelling of buildings has been around for quite a few years, mostly in voluntary schemes. There is also Motiva in Finland, the ELO scheme in Denmark, and Key Numbers in Norway which have been doing for the last 10 years what the Energy Directive sets out to do across Europe. Greece and France both have developed their own methodologies for housing and commercial buildings, and there are also labelling schemes in Australia and the US.

So collectively in the EU and internationally, there is a lot of experience to draw from?

Yes, and of course there are universities and research bodies who have been looking at this area for many years, whether through academic research or in relation to other EU research and demonstration projects. In researching Europrosper we were in contact with all of the major schemes around the world.

What kind of assessment systems are most actively being considered?

There are two fundamental approaches. Europrosper, and all the existing schemes in Europe, use actual energy bills as the basis for assessing performance. The other approach is a modelled study of a building; a desktop study, based on building design and specification information to make a prediction of the energy use. Some methodologies have used the date of construction of a building to estimate the U-values of the envelope based on building regulations current at that time. For new buildings without an energy history a modelled assessment is the only way to predict the performance of the building. But it obviously can’t take into account design faults, workmanship during construction or the operational management of the building. So from the design you predict how much energy the building is expected to use. There are plenty of software packages available and they are currently used in the industry. But the experience of those who do energy audits of buildings is that when they look back and compare the modelled, predicted performance by the design team they find that the building typically uses 2 to 4 times more energy than the model predicted. This can be down to building management, maintenance, a change in use of the building over time or the control systems may not be correctly set up. However it could be the fault of the envelope: perhaps the insulation hasn’t been installed correctly, or the building may not be as airtight as it should be. For example curtain wall systems are often specified with an airtight spec but they are never tested on site because of the difficulty involved, though this is starting to change in the UK. But that’s just the system – how is that system connected to the rest of the building? For example, with a masonry cavity wall next to a curtain wall, the junction may not be tested or specified as being airtight. This is a new area that the industry needs to learn about and be trained to specify and ensure air tightness.

So the main downside of computer based modelling is that is susceptible to inaccuracy?

Well, it is an ideal prediction without knowledge of the actual building. The other way to assess the performance of a building is to use its energy history – the records of what energy has been put into the building in a 12 month period and then to work out, based on the uses in the building and area and volume, how it compares to other buildings of a similar type which are benchmarked. That’s what ECON19 did in a very simple way for office buildings. It established 4 archetypes of office buildings which were typical in the UK , and it is based on actual audits in a database from which benchmarks were derived.

And the Energy Auditors have a more favourable experience of this?

Yes, the auditors’ work, more or less as building detectives, is to find out why the building is using as much energy as it is and to find out what efficient measures could be implemented to reduce consumption. That’s their business. They often get work by promising they can reduce the energy costs of a building by at least 10%, which pays their fees. All further savings go in the owner’s pocket. On a commercial building energy bills can be quite high, so saving 10% can be quite easy because they are often not managed efficiently and the plant isn’t necessarily optimised for maximum efficiency.

There are CIBSE guides which set out basic methods for carrying out auditing. Part of an energy audit is visiting a building to see whether or not, for example, the pipework insulation is missing or if the boiler is out of date and to ascertain how the building is managed. The most common fault is that the default position for switches is to “on” instead of “off”. Many energy consuming systems run all the time unnecessarily.

Can you see a role for other technologies such as thermal imaging or pressure testing?

Yes, but I think that’s almost like doing an ‘NCT’ of a building, and that would be a very detailed and expensive energy audit. I don’t think many auditors do that and it is beyond the intent of the Directive for practical reasons. All buildings in Europe will require a Certificate at some point and that is a huge task.

Should a detailed audit be mandatory?

I think it would be very expensive and that’s its biggest problem. Ideally one could look at a building and, like a car, test the emissions coming out of the boiler, but that would be very expensive. You might want to do during commissioning to ensure the design specification is being met by the contractor / manufacturer. Certainly for air tightness that would be the correct approach. You do the details for air tightness; you specify the materials for air tightness and then put the onus on the contractor that he has to achieve the performance specification. This can then be tested during construction, before the finishes are applied, and remedial action taken.

But the Directive is going to affect existing buildings so it has got to be deliverable and not expensive. Governments would find it very hard to force high auditing costs onto building owners. Some buildings will be very run down and the owners may not have a lot of money behind them, they may have owned it for years and not had the money to modernize it. It would be quite hard to force this on them. Secondly, there may not be the trained personnel to do these assessments if they are too detailed and require a lot of experience.

What is the Europrosper approach to this issue?

Europrosper’s objective was to develop a methodology for assessing the energy performance of buildings based on concepts developed by Bill Bordass, Robert Cohen and John Field who are the authors of ECON 19 and many other publications in this area. Their concept was to use the energy history and put that information, and a few basics about the building, into a software spreadsheet, supported by a database of about 200 buildings they had previously audited, to deduce how the energy would be used by any of the systems in the building. You start with its actual energy use to work out where it is using this energy inefficiently and how to make improvements in its performance. For instance, if you have a 100,000 square foot office building and it uses X kilowatts of gas and X kilowatt hours of electricity and it’s got a mechanical ventilation system, no air-conditioning, a boiler and radiators, a canteen for 20 staff, you can open the windows and it has 4 lifts. The software develops a ‘Tailored Benchmark’ for each particular part of the building: how much energy would be used to ventilate the space, how much for heating it, how much is used by the canteen and how much energy is used in the computer server room or by the lifts. By putting some basic data into the spreadsheet (energy sources, area, volume, and number of workstations ) you can come out the other end with a pretty good deduction of where the energy is being used in a building.

If your ventilation system shows that it is using twice as much energy as the benchmark for that type of building then you would start looking at the ventilation system first as a place to make the building more energy efficient. It’s a deductive process, analysing the building to find out what its performance is and how it compares to similar buildings. But the intention of this directive is to encourage the continuous improvement in the energy efficiency of the building stock. It is not to generate labels; these are the necessary mechanism to trigger the market forces. What is important is that the Directive states that there must be a list of recommended improvement measures as part of the Certificate so that the building owner knows what he must do between this assessment and the next one to improve his building and his label. Before 10 years are up, or if they want to do it sooner, they can get another assessment done and get a better certificate. As they say in Denmark, under their ELO scheme, the label is like the bow tie on the present, it’s the headline that grabs you and it is useful. But the really important thing that they focus on is that the measures proposed should be cost effective and the costs and the benefits of implementing them should be made clear to the building owner.

The audits are to be carried out on a 10 year basis, is this for all buildings?

Yes, the Directive states that a Certificate is valid for 10 years. Personally, I think it should be a shorter time frame. Ten years is a long time in the world we live in, given that the oil industry itself talks about known oil reserves lasting another 30 – 50 years. With China, India and the 10 new EU states all developing and using more energy the increase in demand is likely to increase the cost of fossil fuels. We know we have a limited resource and we know we have global warming so we should become more efficient as quickly as possible. Say we have a situation where an owner achieves a poor rating and they are looking to sell the property and market conditions have changed, consumers are less interested in buildings that have poor energy ratings. Are there any allowances in the directive for people to carry out these audits before transaction? Before the 10 years are up? You can have an audit every year, if you want one. There is no restriction on how often you can have it, only a minimum requirement.

What are the implications for public sector buildings ?

My understanding of the directive is that a public building greater than a 1000 sq metres will need to have a Certificate on 4 January 2006 and that it must be on display in a place where the public is most likely to see it, in a foyer or reception area. The intention is to have the public asking questions of a building they have a stake in. One can imagine it being used in all sorts of situations. Politicians could argue a building shouldn’t be commissioned unless it can achieve a good label.

There is a possibility that if a country cannot implement the directive, for technical or logistical reasons, that there is a three year period during which they must get organized. It is true, unfortunately, that the final deadline for implementation is January 4, 2009 . As I understand that the UK and other countries intend to be up and running by January 4, 2006 which will improve their chances of meeting their Kyoto targets.

Has there been any such commitment here?

Not that I am aware. Most countries are waiting for the CEN standards committee to complete its report by the end of this year which will set EU standards for the detailed implementation of the Directive. We will have to wait to see how Ireland and other countries interpret and implement these standards. One of the concerns about assessing a building on its energy history is that you have to separate the asset from its operation. The argument goes that if you are selling a building, you’re selling an asset and not how it is managed. This however ignores the need for efficient management if we are to reduce our energy use.

So should a building be penalised because the management has not been good even if the building is very good?

The Europrosper methodology does address this and we propose that the label includes both an operational and an asset rating. With new buildings the asset rating might be provisional until an operational rating can be completed after 2 or 3 years. The asset rating can then be modeled on design information and the operational rating can be completed when an energy history is available. (See the proposed label) But we think it is very important that both the asset (the building) and its management (who operate it) should be assessed. The experience of auditors is that the operation of a building can be improved for little or no cost and achieve energy savings of 10 to 25 % immediately. We need to make those savings, especially in Ireland. But if the Government here chooses to use a methodology that focuses on the asset rating, or allows it to exist without an operational rating, a huge opportunity to reduce our energy use will be lost. An operational rating is based on fact, a modelled asset rating is based on estimates and hope. Hope that the building will, or is, working perfectly, exactly as designed and without any poorly installed insulation or poorly commissioned control systems. The difference between an asset and operational rating can be very large. Would an operational rating require the assessor visits the building? The Europrosper approach assumes that for office buildings the auditor would visit the building and talk to the people there, because the indoor environmental quality is to be addressed and you can only do that by actually visiting the building. So visiting the building both to see if there is insulation on the pipe work but also to talk to the building manager to find out things such as whether the building overheats on the west side or is the ventilation sufficient. These issues are important, as we’re talking about buildings where people live and work. We now spend about 90% of our lives in buildings, so their quality is very important. We could build a well-insulated box with no windows and no services and it would be very energy efficient, but we would never see any people inside them. Buildings need to be energy efficient, comfortable, healthy and delightful places. Health is an issue. You can have an airtight building but you need to have very good ventilation, maybe with heat recovery, so that people are breathing high quality, oxygen rich healthy air. There are many overlapping issues involved, and energy efficiency is not the only objective. It is the focus of the directive but it recognizes the importance of indoor quality.

How did you address the issue of quality in your methodology for Europrosper?

Adrian Leaman is part of the Europrosper’s UK team and he, together with Bill Bordass, runs the charity Useable Buildings Trust ( www.usablebuilding.co.uk ). He has developed an indoor environmental quality assessment method for Europrosper based on his post-occupancy evaluation work. The Directive focuses on quantity of energy but does refer to the indoor environmental quality of buildings. What we have proposed in Europrosper is to incorporate this and as part of this methodology we have a spreadsheet that is a distillation of Adrian’s work. It asks certain types of questions to try and find out whether or not people are happy in a building and what the problems might be. There are health and safety issues and with sick building syndrome there are legal and liability issues for employers to cover, as well as energy efficiency. We propose that the label also includes indicators of the building’s indoor environmental quality.

For further information on Europrosper visit www.europrosper.org

The Insider's View

Construct Ireland speaks to Kevin O’Rourke, Head of Built Environment at Sustainable Energy Ireland (SEI). Responsibility for the Implementation of the directive falls between the Department of Environment and the Department of Communications, Marine and Natural Resources. A joint EPBD working group has been established to oversee the planning of the implementation. SEI provides the secretariat for the working group, and has taken a lead role in drafting the action plan for implementing the directive in Ireland .

Are there any particular approaches to auditing that you see as likely or unlikely to be adopted?

Energy auditing or assessment in this context is a two stage process, the first being data gathering (for example by property survey) and the second being calculation. The Directive is very general in the framework it sets out in the Annex regarding calculation, and is silent regarding surveying methods. At this point, no particular methods for surveying or calculation have been ruled in or ruled out. Ireland , along with most other Member States, is closely monitoring the programme of standards being developed by the European Standards body, CEN, under mandate from the EU Commission. While the CEN work is a central resource available to all Member States, it is part of wider European discussions, both formally and informally, on possible approaches to energy auditing. Member States may ultimately choose to apply all, some or none of the emerging CEN standards as mandatory within their jurisdictions. At this point, they are waiting for CEN to deliver, and the picture should be clearer by the end of this year. At this point, the CEN programme will allow for approaches based on simplified calculation methods, relatively complex calculation methods and recorded energy consumption (in the case of certain existing buildings). In all cases, the availability of user-friendly software is envisaged. It is important to note that the main distinction between simplicity and complexity lies in the burden it places on the professional user, particularly in terms of data input. However it should be appreciated that, while a so-called simplified method may require relatively small volumes of data input by the user, partly as a result of its having recourse to inbuilt banks of default data, it may still have a relatively sophisticated calculation engine, using both the input data and default data on which the calculation engine may call. Such default data could include sets of typical weather data to the relevant level of time resolution. It is fair to say that very complex methods are likely to be avoided in practice on grounds of cost and relatively low addition of quality or reliability to the end result, except for very large and complex buildings. It is reasonable to expect that a relatively simplified method of calculation, and associated data gathering, will be applicable to the vast majority of buildings.

What characteristics do you think will be required for the system/s of auditing that are to be implemented, in terms for instance of practicability and accuracy?

Since the outcomes of CEN and other work have yet to emerge, I will comment on the principles or criteria that need to be pursued. You are correct in highlighting the issue of practicability. A system that was impractical would bring the Directive into disrepute. Given the large volume of property transactions to which energy assessments will have to be applied each year, then whatever system/s are adopted must be operable by a sufficient number of qualified professionals who are geographically accessible, to ensure quick turnaround and acceptable cost so as not to present a barrier to such transactions. In this context, the overall accuracy of the result is of course important. But we need to consider what this means in the light of what practical data can be procured by an assessor in relation to the building fabric, ventilation characteristics, heating systems and other building services. It may indeed be more useful to think in terms of relative rather than absolute accuracy, bearing in mind that from the client’s perspective the purpose of the assessment is twofold. Firstly, it will need to present an objective and fair comparative assessment of the property against competing or potentially competing properties. And secondly, it will have to provide a basis for advising the property owner or tenant on realistic options for improving energy performance in use. This is an exercise in consistency as much as precision. Taking the analogy with the motor vehicle and the mpg or l/km energy rating, what is being sought is a clear, credible, consistent comparative basis for informing the energy aspect of judgements on purchase or investment. A similar—though not entirely similar—logic applies to buildings. Some of these criteria need to be addressed in the detailed specification of the method/s to be used and in the design and format of deliverables such as energy performance certificates and advisory reports. Others, such as consistency, will require reliable data gathering and reproducible results from software, which means reliable systems for training and monitoring of assessors. It will also require that proportionate attention to detail is applied in relation to the calculations regarding the building fabric, ventilation and building services aspects. The goal can be described as one of “balanced accuracy”, giving transparent, robust and reproducible results. The method should lead to correct relativities on energy rating or certification, and correct decisions on energy savings measures. In respect of certain low energy building designs, the argument can be made that a complex calculation model is necessary to give credit to an integrated set of low energy features. However, the results from any such model would still need to be seen to be consistent with the scoring framework applicable to the full range of energy performance across all properties. Related to practicability, the other consideration to which all national authorities will be paying keen attention is cost effectiveness. Cost will be most of all dependent on the professional time burden represented by the survey, calculation and reporting processes. In this regard, robust ICT systems supporting both technical and administrative operation have a potentially strong role to play.

Regarding energy auditing, do you think it is likely that different approaches will be applied for commercial, industrial and residential buildings?

Indications from the Directive itself and from wider European discussions are that different methods will apply to housing and to non-residential buildings, in terms of technical scope and complexity. For example, electricity use for lighting is likely to be included in the method for non-residential buildings, whereas it might not be included for housing. It is reasonable to expect that the most simplified methods will apply to residential buildings, which represent a mass market for the energy assessment service and are quite homogeneous in configuration and function. The Directive does not cover “industrial sites”. However, the boundaries between commercial and some industrial buildings are becoming more blurred as we become a more service-based economy. Since commercial buildings in particular tend to be rather diverse in configuration and function, they are likely to require customised assessments. Nevertheless, it is still to be expected that most commercial buildings can be assessed without recourse to the most complex of the calculation and survey methods. A number of research projects are being pursued within the EU seeking to establish pragmatic approaches to assessing such buildings, but whether they yield results applicable to meeting the timeframe set by the Directive remains to be seen.

Do you see different forms of auditing being considered for new build and existing buildings?

Possibly, but I would emphasise that no decisions have been made as of yet. The main point of differentiation is likely to be in the data gathering. On this basis, the practical and cost implications of energy assessment for new buildings would appear to be more straightforward. Here, details – or at least nominal specification details – of the building are available on the drawing board, and it is an incremental exercise for the design team to generate an energy rating for the building. The argument can be advanced that what transpires on site may not match what is on the drawing board, which is a matter for the developer to ensure, under possible inspection from the local authority Building Control function. In the case of existing buildings, data gathering means an on-site survey which is liable to be the most time consuming phase of the assessment. In terms of meeting the criterion of consistency, there is no compelling rationale for taking differing approaches between new build and existing buildings in respect of the calculation procedure itself. However, on the basis of recorded energy consumption data for an existing building representing “missing data”, as it were (data that is “missing” in the case of a new building), the CEN work programme does include consideration of a method involving recorded energy consumption, but its detail and status as a method remains to be developed. Similarly, some EU research work at present is aimed at developing methods for existing buildings starting with an evaluation of existing energy consumption data – something which obviously is not available for new build. Such work may yield an approach to existing buildings which is pragmatic for practitioners to apply, but it remains to be seen whether such methods meet the criteria mentioned earlier as well as meeting the delivery timescales set by the EU Commission

- energy performance

- buildings directive

- renewable energy

- european union

- kyoto protocol

- heat recovery

- building audit

Related items

-

BEAM launch new app for easy MVHR control

BEAM launch new app for easy MVHR control -

Learn about wastewater heat recovery remotely

Learn about wastewater heat recovery remotely -

Circular economy plans come into focus

Circular economy plans come into focus -

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries -

The first oil crisis

The first oil crisis -

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March -

Flynn HRV appoints new design engineer

Flynn HRV appoints new design engineer -

Analysis: 12,000+ homes built in 2017 – as energy standards marginally fall

Analysis: 12,000+ homes built in 2017 – as energy standards marginally fall -

Energywise Ireland open new renewables showroom

Energywise Ireland open new renewables showroom -

Together in Electric Dreams

Together in Electric Dreams -

Simple and stunning Highlands passive house merges old and new

Simple and stunning Highlands passive house merges old and new -

Exclusive: UK may deliver EU sustainable building targets in spite of Brexit – while Scotland & Wales commit

Exclusive: UK may deliver EU sustainable building targets in spite of Brexit – while Scotland & Wales commit