- New build

- Posted

Simple and stunning Highlands passive house merges old and new

While embracing traditional farmstead design made it trickier for this new build home in the Scottish Highlands to meet the coveted passive house standard, mixing modern standards of super-insulation with vernacular farmhouse architecture ultimately led to the creation of a very special home for proprietors Jeanette and Jon Fenwick — one that picked up a coveted UK Passivhaus Award in 2016.

Click here for project specs and suppliers

This article was originally published in issue 19 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

Self-build projects are all encompassing. They take time, mental energy and of course money.

Perhaps this is why many self builders are those who are either approaching retirement or have retired: they have life experience and time to focus — and often their kids have flown the nest. So at this stage, with different wants and needs, what do you build and where?

Jeanette and John Fenwick have always loved the Scottish Highlands and envisaged a retirement there, packed with outdoor pursuits. So they decided to relocate from their three-storey Victorian house in north east England (and escape the house’s 39 steps from top-to-bottom). Their decision to self build came out of necessity, because they simply couldn’t find what they wanted — a contemporary, comfortable and healthy single-storey home with a connection to the rugged Scottish landscape.

As part of their research they attended the Scotland Housing Expo 2010 in Inverness, where they were not only introduced to the passive house concept, but got to visit a terrace of three certified houses that were part of the expo’s innovation showcase. Both Jeanette and John liked what they saw.

Jeanette comments: “The whole concept of not having huge heating bills, and building a house that was going to be comfortable, was important to us.”

With a scientific background, John continued the research on passive house at home: “I just started to google it. And the more and more I read on the internet, the more I decided well, yes, this is the sensible way to build a new house.”

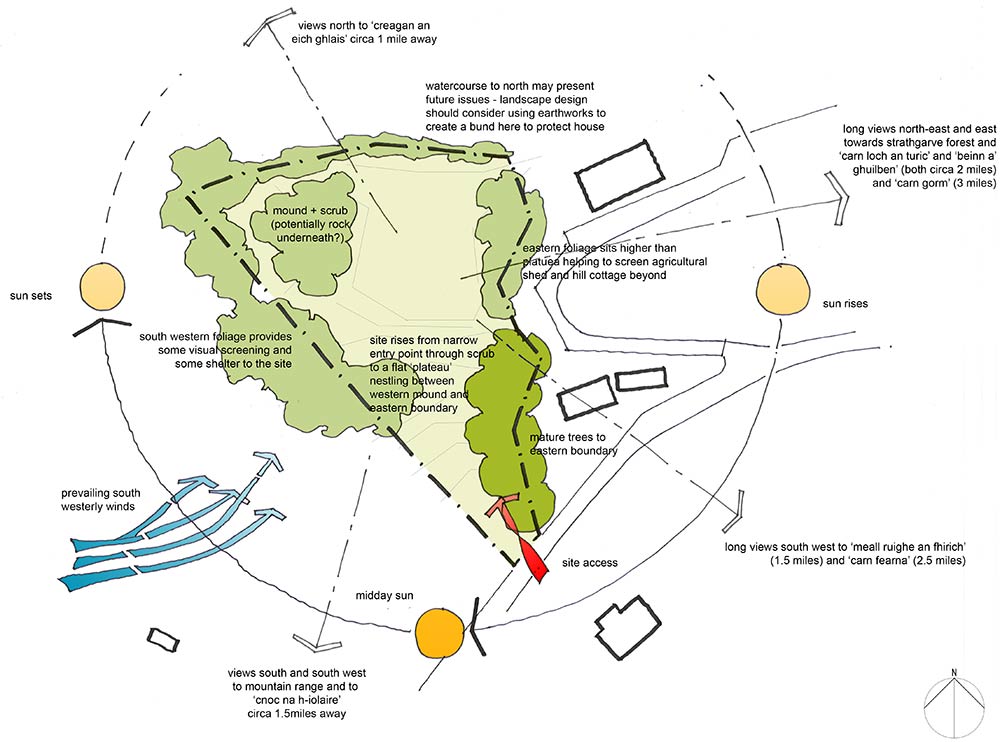

They went on to engage HLM Architects, the firm behind the passive house terrace in Inverness. Having searched online and then visited a number of plots, one stood out. It was just outside the hamlet of Gorstan, a former crofting site, and afforded magnificent views of the Highlands yet was just an hour’s drive to Inverness. The plot was far from straightforward though. There was quite a high water table and a lot of rock on the sloping site. HLM Architects worked closely with Jeanette and John to appraise whether the site was suitable for a passive house, and how they could accommodate their design ideas.

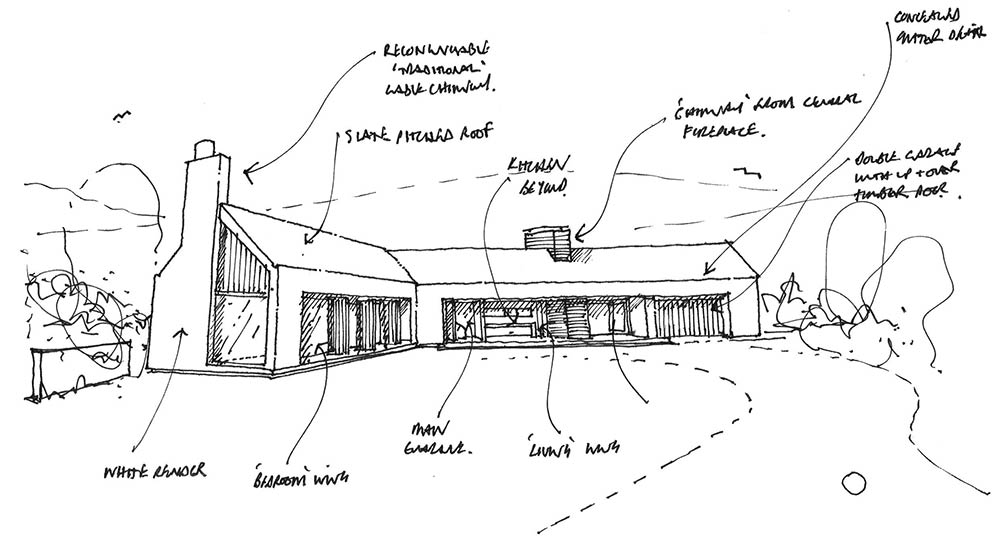

Jeanette explains: “I wanted it to look very much like a traditional house, rather than going for something that was a bit box-like. I like the traditional slate roof and the white rendered look, but [wanted] to contextualise it and give it a contemporary update.”

The kitchen would be the hub of the home, and there would be good connectivity between rooms as well as to the rugged environment outside. They wanted a house far from most people’s perception of a bungalow — a generous, light and airy, modern building, constructed with traditional materials, and incorporating some double height spaces.

The comfortable and even temperatures that passive house affords also influenced Jeanette and John’s decision to put higher, more open plan spaces into the brief.

While passive house design often leans towards a cubic form, Jeanette and John wanted a typical L-shaped farm dwelling, so it was a question of rising to this challenge. As the design responded to the site, the longer living wing was oriented south to make the most of the solar gains, while the bedroom wing faced east to get the benefit of morning sunlight.

Ross Barrett from HLM Architects says: “We were keen to make sure that the main rooms, such as the living room, were double height spaces. That gave us challenges in terms of moving air around the house. Likewise with the bedroom we went for a double height space, and the central space in the house as well.

But it meant we had to, for example, beef up some of the walls to get better U-values, and to look very carefully at the design of the MVHR system to make sure air moved around the house sufficiently.”

The couple considered a ground source heat pump, but the geology of the site would have made installing one tricky. So they opted to install an air source heat pump, which supplies towel rails in bathrooms and a post heater in the MVHR system.

Architect’s design sketch of the L-shaped house, based on traditional farmstead style

The house also features a standalone, room-sealed wood-burning stove in the living room for extra heat on cold days. Not only did Jeanette and John like the idea of having a wood burner in their home, but it made sense because wood is so plentiful in the area. The couple explored the option of a back boiler, but the logistics of concealing the pipework and the length of pipework runs proved to be an obstacle.

There’s one additional heat source on the other side of the house, a far-infrared heater in the main bedroom which also doubles up as a wall mounted full-length mirror. It’s programmed and thermostatically controlled by a wireless thermostat in the room. It’s economical to run, and heats the room and occupants without introducing convection effects into the room.

Planning for the project was relatively straightforward.

When Jeanette and John bought the plot, it already had outline planning permission for a single dwelling and a garage. The new house was then placed in a similar location on the outline plan. The architect took a detailed 3D model of the site and the planned house to a meeting with the planners prior to submitting the application. This, and a detailed design and sustainability statement in the form of an A3 booklet, meant that the planning officer was well briefed in advance of the application, which was approved.

(Clockwise from top left) the plot just outside the hamlet of Gorstan is a former crofting site, and sloping rock and a high water table both proved a challenge here; aerated foundation concrete blocks around the perimeter of the house at ground floor level; vapour control layer taped and sealed to OSB layer on the inside of the timber frame structure; construction of the timber-roof, with the external OSB layer seen here prior to the installation of the breathable roofing membrane and slate finish

The house was constructed with an off-site prefabricated timber frame which is a 300mm deep twin-stud system. The system had also been used for the passive house terrace in Inverness, so Jeanette and John thought it was sensible to go with it, given the architects had already used it to deliver a passive house scheme. However, in the end they had to use an alternative supplier of the panels, which were equivalent in performance, due to the initial supplier closing down.

One of the biggest challenges of the project, it turned out, was finding a contractor to undertake the work. This was largely down to the rural location and the fact that Jeanette and John wanted a fixed price contract. The company that had built the passive house terrace showed interest but didn’t tender.

John says: “We settled with a main contractor who sub-contracted to people that he regularly used for his projects. Some of these turned out to be better than others in appreciating the need for high quality execution of the build to achieve the high level of airtightness the passive house [standard] demands. We had a traditional rather than a design-and-build contract with the architect. He effectively project managed the build and ensured the standards were met.”

Architect Ross Barrett feels one key lesson learned from the project is to involve the airtightness tester early on — thus helping to identify leaks in the airtight layer early, make tradespeople aware of the issues, and rectify them as soon as possible.

Once the timber panels were up, they were clad in blockwork externally, finished with white render. There’s also some limited use of stained timber cladding.

Architect’s site analysis illustration indicating views, orientation, topography and climate conditions on the remote site.

The project took the best part of five years to complete, but John and Jeanette have achieved something special. Natural light is apparent through the oversized windows, and each picks out a different view of the dramatic hills. It’s also worth remembering that the Scottish Highlands frequently dips down to -10C in winter — so a steady 19C inside all year around is quite welcome.

The couple have now been living in the house since the end of 2014. John says: “The one thing that I have noticed which has really surprised us, and I think the reason that passive house works, is because it’s so airtight and so highly insulated you don’t get drafts in the place. I’ve had houses where I’ve tried to control drafts coming up through the floor, through the doors and they’re the things that make you cold. It’s like being out in the wind. But I think the lack of drafts has been the thing that really made it work for me.”

Architect Ross Barrett has estimated that John and Jeanette spent just £157 during 2015 for electricity-based heating, out of a total electricity bill for the year of approximately £835.

Tigh na Croit is one of the most northerly certified passive house schemes in the UK.

Undoubtedly this modern interpretation of a traditional farmstead has been a success.

The strong sense of place and local identity is impressive. Recognisable details of highland rural forms are evident in terms of the chimneys, roof pitch, verges, eaves and carefully placed openings. The house was even the winner in the ‘rural’ category at this year’s UK Passivhaus Awards.

While HLM Architects’ staple is larger projects, there’s a great deal of pride in what they’ve created here. Ross says: “It’s been very important for us as a practice to really try and develop our knowledge and understanding of passive house, and we’re really proud of this building. We think it really is informed by its context, by its site. It really nestles down perfectly well into the site, into the existing contours of the site. There are some great big fantastic oversize windows which allow you to enjoy the views, but at the same time the house is really private. You’re not overlooked, and it’s just a fantastic place for John and Jeanette to enjoy retirement.”

If this project demonstrates anything it’s that a passive house doesn’t restrict designers and that buildings don’t have to be box-like. You might have to work a little harder to reach the standard — but the architecture can lead the way.

Selected project details

Clients: John & Jeanette Fenwick

Architect, project management & passive house design: HLM Architects

Contractor: Urquhart Homes

Structural engineer: Woolgar Hunter

Passive house certification: Passivhusbyran

Drainage engineering: Gunn MacPhee

Mechanical contractor: CJC Plumbing

Electrical contractor: Loch Ness Electricals

Airtightness tester: Airtight Build

Timber frame system: Unitek

Fibreglass insulation: Superglass

Additional wall insulation: Kingspan Insulaton UK

Floor insulation: Kingspan, Tremco Illbruck

Airtightness products: Glidevale

Windows: Internorm

Bespoke window: Katzbeck

Roof windows: Fakro

Air source heat pump: Nibe

Wood burning stove: Ecoliving

MVHR: Paul Scotland

External render: K-Rend

Larch cladding: Russwood

Slate: Siga Natural Slate

Additional info

Building type: 223 sqm TFA detached 1.5 storey new home. Timber frame with external blockwork leaf.

Location: Gorton, Ross-shire

Completion date: Nov 2014

Budget: £356,000

Passive house certification: Certified passive house

Space heating demand (PHPP): 15 kWh/m2/yr

Heat load (PHPP): 13.4 W/m2

Primary energy demand (PHPP): 97 kWh/m2/yr

Environmental assessment method: Scottish Sustainable Building Regs Section 7, Silver Active label (+ Part Gold)

Airtightness (at 50 Pascals): 0.6 ACH Energy performance certificate (EPC): C 79

Measured energy consumption: Based on electricity bills, 8275kWh / 37.1 kWh/m2/ yr total electricity consumption (so including heat pump and all appliances, but not wood burning stove) for 2015 calendar year. Total electricity bill for 2015 estimated at £835 (10.09p per kWh) plus £57 standing charges. By subtracting measurements and estimations of non-heating related electricity usage, electrically-based heating during 2015 (air source heat pump, infrared panel) is estimated at 1156 kWh during 2015, or 7 kWh/m2/yr (cost of £157).

Thermal bridging: Thermal bridging designed out / minimised through use of timber frame. All window reveals insulated. All junctions / details thermally modelled.

Ground floor: 140mm aerated foundation blocks, 150mm thick concrete slab on separating layer over 200mm Kingspan TF70 Insulation, with 100mm insulation to slab edges. U-value: 0.1 W/m2K

External walls (render): Acrylic K-Rend render on 100mm dense block, followed inside by 50mm cavity, on thermal breather membrane, on 10mm OSB, on prefabricated twin frame consisting of 140mm SW stud, gap, 70mm SW (studs packed with 300mm mineral wool insulation), 10mm OSB to inside face with vapour control layer taped and sealed, service gap formed of 38mm SW battens, 12.5mm plasterboard taped and filled. U-value: 0.11 W/m2K

External walls (timber clad): Locally sourced Scottish larch (stained grey) on SW battens/ counter battens on thermal breather membrane, on 10mm OSB, on prefabricated twin frame consisting of 140mm SW stud, gap, 70mm SW (studs packed with 300mm mineral wool insulation), 10mm OSB to inside face with vapour control layer taped and sealed, service gap formed of 38mm SW battens, 12.5mm plasterboard taped and filled. U-value: 0.12 W/m2K

Roof: Siga slate on battens / counter battens, on breathable roofing membrane, on 10mm OSB, on 300mm I-joists packed with 300mm mineral wool, on 10mm OSB to inside face with vapour control layer taped and sealed, 50mm service gap formed of 50x50mm SW battens, 12.5mm plasterboard taped and filled. U-value: 0.12 W/m2K

Windows: Internorm Edition composite timber / aluminium triple-glazed argon filled windows. U-value: 0.8 W/m2K

Roof Windows: Fakro FTT U8 quadrupleglazed composite timber / aluminium centre pivot windows. U-value: 0.68 W/m2K

Heating system: NIBE F2015 air source heat pump (COP 4.21) with 200L tank and buffer supplying wet towel rails (by heating circuit) to bathroom / en-suites, water-based post heater in MVHR. Electric infra-red panel heater to bedroom. 5kW Contura 51L wood burning stove with ducted air supply.

Ventilation: PAUL Novus 300 heat recovery ventilation system (92% efficient according to PH Certification) complete with water based post heater.

Lighting: Low energy LED lighting throughout.

-

First floor plan Stage D

First floor plan Stage D

First floor plan Stage D

First floor plan Stage D

-

Ground floor plan Stage D

Ground floor plan Stage D

Ground floor plan Stage D

Ground floor plan Stage D

-

Elevations

Elevations

Elevations

Elevations

-

Typical eaves details

Typical eaves details

Typical eaves details

Typical eaves details

https://passivehouseplus.ie/magazine/new-build/simple-and-stunning-highlands-passive-house-merges-old-and-new#sigProIda6c76e891a