- Case Studies

- Posted

Creature comforts

Not only does the new OPW-designed district veterinary office in Drumshanbo Co. Leitrim place strong emphasis on natural ventilation and lighting, it rests comfortably in the rural landscape and boats commendable green features too. Lenny Antonelli reports

Sitting in the rolling Leitrim countryside, just outside Drumshanbo village, the Department of Agriculture's new district veterinary office is integrated with its rural surroundings in more ways than one. Designed to sit comfortably in the landscape, the building is largely illuminated and ventilated by its environment too.

Completed in April, the 2,800 square metre office building was designed by the Office of Public Works and can hold up to 110 staff. The list of green features on site includes natural ventilation and lighting, a well insulated structure, solar thermal panels, recycled construction materials and facilities for cyclists.

Fitting with the landscape was a priority for architect Sean Moylan. "Because the ground floor is clad with stone, it gives the impression of a building that's firmly rooted in the landscape," he says. In contrast, most first floor elements are clad with timber to give them a less permanent and warmer appearance.

Stone is an integral part of the Irish landscape though, and the building is designed to reflect that. Internally, the exposed concrete walls are plastered to create a smooth concrete finish. As you move outside, the rectangular stone cladding of the ground floor comes into view. Further out, a random rubble stone wall surrounds the site. "All the time as you come out from the entrance the finishes get rougher and rougher as you start to merge with the landscape," Moylan says.

The building was designed around an entrance courtyard – an obvious focal point. "Entry to the building is through a sheltered space to get out of the Leitrim wet and wind. It's not just an abrupt entry." A second courtyard functions as a light-well.

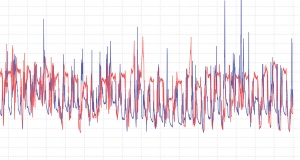

Natural lighting and ventilation strategies are at the heart of the building's design. While reducing heat demand is the priority in residential build, the biggest energy hogs in office buildings are typically cooling and lighting. Both the lighting and ventilation strategies were digitally simulated and tweaked during the design phase to test their performance.

The OPW employed similar strategies at the Department of Agriculture's food safety offices in Kildare, profiled by Construct Ireland last year. By creating slender open-plan offices with openable windows along both sides, there was little need for artificial lighting or ventilation there. The design at Drumshanbo is somewhat similar. The open plan office on the first floor is ventilated simply by opening the windows – the internal space is slim enough to ensure sunlight and air can penetrate throughout.

Natural lighting and ventilation strategies were central to the design

The Dept. of Agriculture’s new district veterinary office in Drumshanbo, Leitrim

In other areas of the first floor, a passive stack ventilation system uses wind as a source of natural ventilation. Fresh air is carried passively from wind cowls on the roof through ducts to the floor below. The cowls capture the prevailing wind regardless of its direction, and turn it down through a 90 degree angle before delivering it to the space below. At the same time, the difference between the indoor and outdoor temperatures creates a pressure gradient that causes stale warm air to rise up and out of the building.

Dampers in the cowls control the volume of air coming in, and can be automated to open at specific temperatures, CO2 concentrations, or humidity levels. If the temperature drops too low, the dampers close to prevent overcooling. On summer nights they open fully to ensure indoor air is fresh each morning. The passive stack system has no moving parts and thus requires little maintenance, and it can be used to ventilate multiple floors of a building.

An iroko brise soleil along the southern and western facades also helps to passively cool the building. Essentially a series of outdoor timber blinds running horizontally along glazed sections, the brise soleil shades the interior to prevent overheating and glare. To avoid interrupting general eye level, it doesn't come down below a height of 1.8m. "It's like a Venetian blind and is set at an optimum angle of 60 degrees," Sean Moylan says.

The entrance courtyard forms an obvious focal point of the building

A mechanical air handling system in the floor also helps cool the building. If the temperature inside at night is sufficiently warmer than outdoors, fans kick in and blow fresh air under the raised access floor and up into the space above. The cool air makes contact with the exposed concrete slab inside, cooling it down. OPW mechanical and electrical engineer Frank Reilly says the system's electricity consumption is low. Downstairs two meeting rooms are cooled by local air conditioning units, and other rooms are manually ventilated with openable windows.

Floor-to-ceiling windows allow generous sunlight into the building so there's little need for electrical lighting. The artificial lighting system – consisting of T5 flourescent tubes – is automated so lights only come on when needed. "They work on the basis of occupancy,” Frank Reilly says. “If there's nobody there the lights don't come on in the space, and when the daylight exceeds 500 lux the lights start dimming.” The lux is a unit that measures the intensity of light.

"The level of mechanical ventilation and cooling is small," Frank Reilly adds. "Air conditioning would be a huge energy draw in an air conditioned building. The biggest draw of energy here I suppose would be the lighting and we've reduced a lot of that really with the occupancy sensors and the dimming.”

The OPW plans to subject buildings it has designed – including the Drumshanbo veterinary offices – to a 'BREEAM for Ireland' assessment. BREEAM – the Building Research Establishment's environmental assessment method – rates buildings based on their environmental performance, in areas such as energy use, transport, water, materials, land use and waste.

The OPW specified an aluminum double-glazed cassette window system throughout, featuring double thermal breaks and argon-filled cavities. "It's a fairly standard casette type system, but it's a very high performance system," Sean Moylan says.

Windows are recessed back about 400mm on the first floor. On the ground floor they're projected forward about 20mm. "[Downstairs] they look more or less like picture frames hung on the wall, so they kind of express that impenetrability of the stone itself."

Working with a thermodynamic model of the building at the outset, the designers could simulate how the glazing specification would effect the building's thermal performance. "That identified areas where we had too much glazing versus too little glazing," Moylan says.

The OPW chose a reinforced concrete construction for the walls. All concrete used contains 50 per cent ground granulated blastfurnace slag (GGBS), a cement replacement derived from steel industry wastes without the high carbon footprint of traditional cement. Traditional concrete is responsible for approximately 5 per cent of global carbon dioxide emissions.

The 2,800 square metre building was completed in April and can hold up to 110 staff

The exposed concrete walls are effective at soaking up and storing heat while

Inside, the plastered concrete is exposed in much of the building, providing thermal mass to help balance out temperature fluctuations. Exposed concrete is effective at soaking up and storing heat, which it then releases slowly to the internal space.

The external side of the concrete walls was insulated with 100mm of high performance rigid phenolic insulation. Outside, the building is clad with stone and iroko – mostly stone on the ground floor and timber on the first. The 38mm iroko timber board has an estimated lifespan of 40 years, Sean Moylan says.

An iroko brise soleil helps to prevent glare and overheating

Speaking to Construct Ireland last year about the food safety offices at Backweston, OPW assistant principal architect Ciaran O'Connor said the organisation's timber specification favours "timber from properly looked after forests." He said the OPW requires documented certification on where all its timber is sourced.

O'Connor was especially familiar with Ghanaian iroko, the variety used at both Beckweston and Drumshanbo. He believes the variety is often wrongly tarred with the same brush as timber from other African countries. "Ghanaian foresty is on the cusp of meeting sustainable standards. The level of corruption is certainly much lower than most African countries,” he said.

The OPW landscaped two acres around the building, planting clusters of native trees to mimic the landscape

|

The OPW specified a trocal roofing system for the building, insulated throughout with a minimum of 100mm of rigid phenolic board insulation. Trocal is a PVC-based product. The floor is also insulated with 100mm of a rigid phenolic board.

With no gas grid nearby, two 240kW high efficiency modulating oil boilers heat the building. The OPW considered a wood pellet boiler, but ruled it out because of concerns over price and supply. "We did an analysis and the most cost-effective [system] at the time was oil so we ran with oil," Frank Reilly says. The building has been designed to accommodate a biomass boiler in future. The OPW plans to monitor its electricity and oil consumption closely over the next year.

Throughout most of the building, heat is distributed via trench heaters set into the raised access floor. The main foyer has underfloor heating though, while some rooms have low pressure hot water (LPHW) radiators.

"Each one of the trench heaters is provided with a motorised valve that's linked to the building management system," Frank Reilly says. "They sense the internal space temperature and throttle down the valves accordingly. In addition to that, there's a weather compensator on the boiler water temperature out, so the milder it is outside, the lower the boiler water temperature is."

An 8 square metre array of solar evacuated tubes helps meet hot water demand. But like most office buildings, the hot water requirement is quite low at Drumshanbo. Evacuated tubes are a common alternative to flate plate panels, and are designed to reduce heat lost through convection and conduction. They're generally regarded as being more effective than flat plates in winter but not as efficient in summer.

Ample facilities for cyclists were included in the design - there are 20 bicycle parking spaces outside, as well as showers and locker facilities in the building. Outside, the OPW landscaped two acres around the building. "The landscaping was based on creating groves of trees so it'd be harmonious with the natural landscape itself," Sean Moylan says. "You never see rows and rows of trees in the countryside growing naturally."

Existing hedgerows and trees around the site were retained. The planting scheme emphasises native species like ash, rowan, holly, hawthorn and alder. Fast-growing birch was planted to screen the immature trees and hedges as they grow, but will be removed after ten years or so.

Considering the attention paid to ensuring that the building itself is comfortable in its rural home, it's hardly surprising the landscaping was designed to mimic the local environment. The Irish countryside is certainly more accustomed to large buildings being out of sync with the landscape than in. But through clever use of stone and timber, and emphasis on passive ventilation and lighting, the OPW has created a building that is not just at home in its local environment, but that brings it to the heart of how it functions too.

- Articles

- Case Studies

- Creature comforts

- Drumshanbo

- Office of Public Works

- natural ventilation

- iroko brise soleil

- stack ventilation

Related items

-

It's a lovely house to live in now

It's a lovely house to live in now -

Woodland wonder

Woodland wonder -

The stunning low energy seaside home that's built from clay

The stunning low energy seaside home that's built from clay -

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather -

Life in an air-heated passive house - Five years on

Life in an air-heated passive house - Five years on -

Affordable homes scheme reflects rise of Norwich as a passive hub

Affordable homes scheme reflects rise of Norwich as a passive hub -

Larch-clad passive house inspired by a venn diagram.

Larch-clad passive house inspired by a venn diagram. -

389 sqm home, €200 measured annual heating

389 sqm home, €200 measured annual heating -

Mechanical ventilation and IAQ - what the evidence reveals

Mechanical ventilation and IAQ - what the evidence reveals -

Low energy Tipperary offices go for gold

Low energy Tipperary offices go for gold -

Natural ventilation - does it work?

Natural ventilation - does it work? -

Opinion