- Passive Housing

- Posted

Passive aggressive

Imagine moving into a house without a heating system – what would you do? Contact the developer and demand they put one in immediately? Call a solicitor and sue the builder? Or sit back and enjoy living in a house, designed to meet your expectations of comfort without any recourse to a space heating system. Jason Walsh met the people behind Ireland’s drive toward the passive house.

Designed to ultra-low energy use standards, passive houses require little or no energy for space heating or cooling. The first passive buildings were built in Darmstadt, Germany in 1990 and occupied in 1991. The concept of the voluntary standard was pioneered by Dr. Wolfgang Feist, who went on to found the Passivhaus Institut in 1996. The institute operates as an independent research institution employing building physicists, mathematicians and civil, mechanical and environmental engineers to perform research and development on efficient energy use.

Currently Ireland has only one certified passive house, a fact which appears to contradict claims of a growing groundswell of interest. However, dozens of other homes have been designed and built as passive houses, with many more at the planning stage. Passivhaus Institut certified products are finding their way onto the market, with prominent examples including windows from companies such as Optiwin, Internorm and Niveau. Add to this the roughly 70 Irish delegates including developers, architects, sustainable product suppliers and local authority officials who attended the recent 2008 Passivhaus Institut conference in Nuremberg, and Irish interest in the passive house is confirmed.

“It’s an explosion,” said architect and passive house specialist Tomás Ó Leary, “with the rapid changes in the building regulations we’re effectively heading for passive houses to be standard.”

Ó Leary built Ireland’s first officially certified passive house – his own home – in 2005. Located in Ballykeppogue, County Wicklow, Ó Leary’s house has served as something of a prototype with Ó Leary’s architectural practice MosArt terming-up with consulting engineers Energy 365 to open a passive house ‘centre of excellence’ in Rathnew, County Wicklow late last year.

Since then there has been a massive growth of interest in passive houses but regulatory developments are also having an effect. After an unprecedented 40% energy and carbon dioxide reduction kicks in to Part L of the Building Regulations in July, an additional 20% reduction has been signaled for 2010. This should bring our regulations within touching distance of the passive house standard, prompting some to ask why the country can’t go that little bit further and implement the passive standard as a basic requirement for all Irish housing.

The usual objection to passive houses is that the standard is simply too difficult to meet. In fact, the basic requirements for a passive house are relatively simple: attention to detail in orientation and use of passive solar, good insulation, good glazing, heat recovery ventilation and, crucially, air-tightness.

Two distinctly different approaches to building passive houses exist in projects by Scandinavian Homes (title pic) and MosArt (above)

The ground floor plan of MosArt’s first passive house

As a result of differences in climate the passive house is actually something of a moveable feast: requirements in a relatively mild climate such as is experienced in Ireland are a lot less stringent than in colder countries such as Germany, Sweden or Austria. This fact has recently been spelt-out in detail in a new Sustainable Energy Ireland document authored by Tomás Ó Leary.1

The document, Passive Homes: Guidelines for the Design and Construction of Passive House Dwellings in Ireland, has been lauded across the energy and construction sectors. Ó Leary’s key insight is that Ireland’s climate makes passive houses affordable and easily achievable.

Sustainable Energy Ireland’s Paul Dykes told Construct Ireland that the recently published document has already been a success: “We’ve distributed over 500 hard copies and 3,500 CDs,” he said.

“The point is to raise awareness of the concept and ensure that developers and architects have access to the guidelines and the right standards,” he said.

Energy consumption rates have begun to decline exponentially in typical Irish houses over the last number of years. This has come mostly as a result of improved insulation, something which is vital in a passive house. However, a key difficulty facing potential builders – and buyers – of passive houses is air-tightness.

“It’s down to having a good building culture,” said Ó Leary. “Air-tightness is the crucial factor.”

MosArt’s Tomás Ó Leary

Air-tightness is vital in a passive house as it facilitates the use of heat recovery ventilation (HRV) for space heating. Unfortunately, air-tightness is not something that Irish houses are renowned for, meaning that potential buyers and self-builders would be well advised to seek out experts in the field before committing to a project.

SEI’s guidelines state that the air-leakage must not exceed 0.6 air changes per hour using 50 Pa over-pressurisation and under-pressurisation testing.

“50 Pa is like a tornado hitting your windows,” said Ó Leary. “A [traditional] Irish house will typically achieve a very poor air-tightness level.”

“The reason that the passive house concept is gaining such a foothold in Germany and spreading out from there is because of the simple win, win, win strategy it entails,” said David McHugh or heat recovery ventilation specialists Pro Air.

“The end user wins because he knows that not only will his heating bills stop rising each year but will disappear altogether after the initial investment. The low energy industry wins because their product now becomes recognised as a value for money investment. Everybody else wins because the elimination of heating and cooling systems in buildings could reduce our CO2 emissions by an impressive 40 per cent.

“The strategy to be adopted in attaining a passive building is to insulate, seal and ventilate it efficiently,” he said.

“Dr. Feist used the following three pronged strategy when he sat down in 1988 to design his dream home. As an engineer he knew the challenge lay in halting the migration of heat from inside to outside, stop the movement of cold air through the structure, to insulate and provide a healthy living comfortable indoor environment. To get these components right involved some calculations which we now take for granted. He had to calculate the amount of heat that a normal family, in an average house, would create by their activities, in watts at any one time and then annualise this into kilowatt hours. Having devised a figure for this he could work out the levels of insulation necessary to prevent this heat escaping.

Wolf Passive Homes’ show house in Kildare, (above) the front of which faces North whilst the rear (below) faces south and therefore includes substantially more glazing

“As the construction progressed it was necessary to pressure test the house to ensure that no draughts from outside existed within the house. His third challenge was the creation and maintenance of satisfactory indoor air quality. Heat exchanger technology, at this time was in its infancy but he managed to source a system which would utilise the heat of air being extracted to warm air on its way in. Another major factor in his strategy was to encourage low winter sun light deep into the house and discourage the high, strong rays of the summer sun.”

Sheep in wolf’s clothing

More and more companies are moving into the passive house field. Acting as both a show home and a real dwelling, Wolf Passive Homes has now built its first passive house, entering the Irish market.

Wolf Passive Homes’ Sean Dunne explains: “It’s in Newbridge, County Kildare. It’s our first passive house in Ireland. I sold my old house at the beginning of the year and have moved into the passive house.”

Dunne’s professional background is interesting insofar as it could be seen as a ringing endorsement of the passive house, once seen as a fringe idea, by the mainstream. He worked as a director of a German bank’s Irish operations at the IFSC for sixteen years. Dunne says that it was during his time at the bank that he began to become aware of sustainability: “I’d seen quite a lot of renewable energy products coming into Ireland over the years but I also came across some wonderful products, particularly in the building industry.

“Furthermore, I wanted to give something back,” he said.

“We built this house so that people could come and find out what a passive house was all about,” said Dunne. “In the meantime I’d been to Germany and looked at some passive houses and had an idea of what to expect. What interested me was the quality of passive houses and their cost-effectiveness. I found it fascinating that we would never have an oil truck backing-in again.”

In the interests of comfort and, above all, psychological security Dunne did install a space heating system in his house. It has never been used.

“We have a pellet-burning stove but we [eventually] sealed-up the flu when we realised we would never need it,” he said.

It transpires that even in the depths of winter Dunne’s home is comfortable: “In January after moving in we got the temperature up to twenty degrees Celsius. The current temperature [in April] is 20.5 degrees.”

Dunne notes that passive house don’t offer much in the way of ‘excitement’ through gadgetry: “A passive house is perhaps boring because the room temperature is the same in every room.”

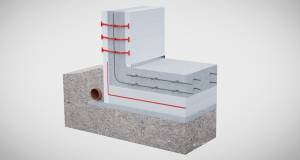

In the public mind passive houses and timber frame construction are strongly linked but Wolf Passive Homes’ dwellings are constructed from insulated concrete formwork (ICF). Dunne says that Wolf’s ICF has specific advantages that its competitors don’t: “The reason I chose it over other ICF was that this company has a polystyrene base that creates an air-tight envelope. Most other ICFs didn’t offer that, they were more like traditional builds and fifteen per cent of heat loss is through the ground.

“When you pour the concrete it becomes air-tight and the heat builds up. My house is 0.46 [air changes per hour at 50] Pa. During the test we identifies a couple of thermal bridges – windows that weren’t fully sealed – so we corrected that.”

Indeed, both air-tightness and good insulation are central to the entire passive house concept, something that is as true of this two storey, 4,500 square feet (418 square metres) dwelling as it is of any other. The house’s north-facing orientation goes some way to proving that the need for passive solar gain doesn’t mean all buildings must be south-facing: “All of the large windows are to the rear which is southerly” explained Dunne.

The house contains a heat recovery ventilation system which contributes approximately six kilowatts of heat - suitably small amount for such a negligible heat requirement.

The 44 centimetre-thick walls achieve a U-value of 0.098 and the base has a U-value of 0.13. The roof uses a 28 centimetre-thick polystyrene block with a steel profile and achieves a u-value of 0.12.

For Dunne this first house was a hands-on project: “It was designed by my wife and I. We employed a local architect, Derek White, who it’s fair to say has embraced the passive house concept.”

According to Dunne there is growing interest in passive houses, despite the fact that it’s early days for Wolf Passive Homes: “People are becoming more familiar with what a passive house is. The building energy rating (BER) and the recent initiatives by the Green party are helping but it will take time.” He also pointed to popular television programmes such as Channel Four’s Grand Designs and RTÉ’s About the House, presented by EASCA founder Duncan Stewart, as helping to raise awareness of the issues.

From Germany with love

German architect Herman Richter has built a passive house in Swords, County Dublin. Richter’s firm, German Eco Homes, has offices in Dublin and Schweinfurt, Germany and is something of a one-stop shop for passive houses, offering architectural design, timber frame manufacturing, contracting and building.

Richter told Construct Ireland how the project got started: “The customer located us on the ‘net – they specifically wanted a passive house,” he said. “We did the planning – we have an in-house planning department [so] we applied for planning permission and got it in a very short time. There was just one meeting with the planner and there were no objections.

The SurTec building in Zwingenberg

On the continent the passive house approach ha taken off to such an extent that even large commercial buildings are being built to its specifications, such as “lu-teco” a 10,000 sq m office building with 10.000 situated in the technology mile of Ludwigshafen and the SurTec building in Zwingenberg

“The house itself is a two storey building with a traditional appearance. It’s oriented exactly to the south – we could do that because of the site.”

Also on the site is the occupant’s previous home, a traditional concrete-built bungalow dating back to the 1960s. It is now used solely for storage.

Lars Pettersson of Scandinavian Homes

“The new house has a 300 square metre living space – two storeys plus an attic space – and we will [soon] have certification from the Passivhaus Institut. The walls are timber frame construction – 240 millimetres with cellulose insulation.”

Richter explains that German Eco Homes builds with natural materials: “We don’t use a plastic vapour barrier membrane. We don’t need it because it’s a breathable construction. On the outside we have a 350 millimetre wood-fibre board and a Tyvek breathable membrane, a ventilated cavity and plastered cement board.

“All of the materials are of natural origin – mostly they’re recycled wood products. We want the lowest CO2 production. The timber itself is dry and there is no movement after construction.”

Richter argues that it would be foolhardy to build a house with no heating system whatever, even a passive house: “Every house needs a back-up heating system for very cold days [nevertheless] 75 or 80 per cent of the heating is through passive solar gains.”

The additional heating in Richter’s houses is provided by heat recovery ventilation. In addition, the old house’s oil boiler was not decommissioned, though it has not been used as yet. Finally, solar panels provide domestic hot water.

Not all of Richter’s designs are strict passive houses: “We also build low-energy houses. In Germany it’s harder to build a passive house due to the colder climate. A German low-energy house virtually meets the passive house requirements in Ireland. It needs a little more insulation and triple-glazed windows.

“I think the passive house is very easy to build in Ireland – the advantage of the higher winter temperature is vital,” said Richter. “Our [energy consumption] target is 15 kilowatt hours per metre square, per year.

“The known issue with passive houses is air-tightness,” he said. “We have to achieve an air exchange rate of 0.6 minimum. This can be a problem if you’re not used to it and don’t have the experience.”

Northern exposure

Aside from Ó Leary, Ireland’s pioneer in passive houses is Scandinavian Homes. The County Galway-based firm has been building near passive homes since the early 1990s, before increasing the spec to passive house levels in 2005. The firm’s founder Lars Pettersson, regarded as something of an expert in the field, is concerned that passive houses are suffering in Ireland as a result of the building energy rating (BER) scheme.

Pettersson stresses that his own houses, for example, achieve high B-ratings rather than the expected A-ratings as a result of use of electrical energy to heat bathroom floors for comfort.

“It’s very serious. It means that people building passive houses could get a poor rating. It discriminates against better housing,” he said.

It could be said that Pettersson’s concerns are motivated by his financial interest in selling passive houses but there is something more to his argument than commerce. At heart, Pettersson is making a democratic complaint: “We want to make [passive housing] available to ordinary people. The idea is to have 50 square metres per person – that’s not frugal, but it’s not over the top either.”

Relatedly, Pettersson argues that the increasing complexity of some passive house designs is a problem: “Since they were introduced in the 1990s they’ve become more complicated. In Germany they are becoming a luxurious thing for the few. That’s the way things are going over here too. They overcompensate with pellet burners, heat pumps and all sorts of complicated systems.

“Many look like nuclear power plants in terms of all the [complex] equipment in them,” he said. “It’s misleading to put so much effort into other things when heating is the most important issue. In a mild climate like Ireland you should be able to get away from space heating.”

For Pettersson the negative focus on electrical energy is wrongheaded: “I’m quite annoyed with all of this ‘zero carbon house’ business. My position is that you should be able to have a house without heating but that won’t sort out your refrigeration and lighting, for example.

“Solar water heating can sort out your water needs for most of the year. If you use electricity for two months to top it up, so what?” he said. “Electricity is fine if it’s used appropriately. It should not be wasted on space heating unless the home is so efficient that it’s pointless to install lots of complicated equipment.”

This is the nub of Pettersson’s argument: passive houses are so efficient that a small amount of electrical energy used to heat bathroom floors and top-up hot water in the winter should be a non-issue but under the current BER regime, homeowners will be penalised for doing so.

“We use 810 watts to heat 250 square metres. That’s 3.24 watts per square metre – that’s all we need in Ireland’s mild climate.

“You have to decide if you’re going to measure the energy balance in a house or its performance,” said Pettersson. “Our view is that it should be on the basis of performance. Currently, if a house has a windmill it’s rated as a better house. That way you can get away with building terribly bad houses, throwing on a couple of photovoltaic panels and a bit of a windmill and get an A2- or A3-rating. That’s the Irish way.”

Pettersson explains that the design of passive houses makes for better energy efficiency and that this should be reflected in BER ratings: “The passive idea originally was a maximum of 50 square metres per person meaning the average family home is 100 to 200 square metres. This makes it possible to reach the passive standard in a relatively easy way: the idea was that the little [heat recovery] ventilation system could move the heat around.”

In arguing for recognition of designed sustainability before retrofitted mechanical systems Pettersson sums up the key benefit of passive houses succinctly: “By investing in the money you would otherwise spend on a complex heating system such as wood pellet or geothermal in insulation and air-tightness you don’t need complex systems.” Early signs however are that many of the Irish people looking to build passive houses are erring on the side of caution, and including small space heating systems, just in case they’re needed.

1 See: http://www.sei.ie/getFile.asp?FC_ID=3453&docID=59

- Articles

- Passive Housing

- Passive Agressive

- Wolf Passive Homes

- insulated concrete formwork

- German Eco Homes

- Passivhaus Institut

Related items

-

Up to 11

Up to 11 -

Podcast: what we've learned from 20 years in green building mags

Podcast: what we've learned from 20 years in green building mags -

Superb airtightness result for Manchester ICF house

Superb airtightness result for Manchester ICF house -

ICF fast & reliable for social housing — Amvic Ireland

ICF fast & reliable for social housing — Amvic Ireland -

Passive Building Structures aims to cut carbon both on & off site

Passive Building Structures aims to cut carbon both on & off site -

Amvic Ireland launches passive standard ICF system

Amvic Ireland launches passive standard ICF system -

Passive Building Structures delivers bespoke Manchester passive house

Passive Building Structures delivers bespoke Manchester passive house -

Amvic ICF delivers rapid build NZEB schemes

Amvic ICF delivers rapid build NZEB schemes -

Monolith ensures traditional finish on new ICF project

Monolith ensures traditional finish on new ICF project -

VRM Tech aim to digitise passive house building

VRM Tech aim to digitise passive house building -

Amvic Ireland ICF gets updated Agrément cert

Amvic Ireland ICF gets updated Agrément cert -

Two new low energy schemes built with Amvic ICF

Two new low energy schemes built with Amvic ICF