- Oil Peak

- Posted

Peak timing

As the organisation entrusted by OECD countries to predict future global energy supplies, the International Energy Agency’s projections have significant impact on energy policy around the world. IEA officials recently told The Guardian that the organisation’s figures on oil supply had been inflated and that oil peak is happening. Richard Douthwaite assesses the fall outIn the run-up to the recent Copenhagen climate conference, the world's media got great mileage out of claims that some of the world's leading climate scientists had been fudging their data to disguise a recent decline in global temperatures. The scientists had, in fact, been doing nothing of the sort. The worst they did was to use in-group language in e-mails to colleagues and made life hard for other researchers who did not share their interpretation of what is going on. A good explanation for their behaviour can be found at tiny.cc/cipew

The reason the falsification claims were taken up so readily is that it would be a great relief for everybody if we suddenly found that warming had gone into reverse and we could stop worrying about burning all the fossil fuel we could get. In fact, of course, the evidence for a continuing rise in temperatures is incontrovertible – you just have to look at photographs taken a few years apart showing the retreat of glaciers or the ice around the North Pole. In any case, as many people pointed out, the University of East Anglia's Climate Research Unit's figures could not have been seriously distorted because other groups working quite independently have produced data showing the same thing – namely that the decade which is ending has been the warmest since records began 160 years ago and 2009 ranks among the top ten warmest years.

Unfortunately, this false ‘scandal’ may have diverted public attention from a real one which The Guardian had partially exposed ten days earlier. The real scandal is that the International Energy Agency, which was set up as an arm of the OECD to provide rich-country governments with energy policy advice, has been deliberately misleading the world about the adequacy of future oil supplies.

“Key oil figures were distorted by US pressure, says whistleblower” was The Guardian's front-page-lead headline on 9 November over a story which quoted a current senior IEA employee and a former one. "The IEA in 2005 was predicting oil supplies could rise as high as 120m barrels a day by 2030 although it was forced to reduce this gradually to 116m and then 105m last year," the current employee was quoted as saying.

"The 120m figure always was nonsense but even today's number is much higher than can be justified and the IEA knows this,” he continued. "Many inside the organisation believe that maintaining oil supplies at even 90m to 95m barrels a day would be impossible but there are fears that panic could spread on the financial markets if the figures were brought down further. And the Americans fear the end of oil supremacy because it would threaten their power over access to oil resources."

The former employee said a key rule in the IEA was that it was "imperative not to anger the Americans" but the fact was that there was not as much oil in the world as had been admitted. "We have [already] entered the 'peak oil' zone. I think that the situation is really bad," he added.

What The Guardian missed was that the deception has been going on for ten years rather than five. As a result, politicians have had false confidence about the ready availability of oil through all those years. This has not only delayed the global transition to renewable energy but has also inhibited the world's response to the climate crisis. The combined effects of both results could cost millions of people their lives.

The deception began in 1999, about a year after a retired oil man and West Cork resident, Dr Colin Campbell, had convinced an IEA team that oil depletion was a serious problem. Campbell’s own interest in the rate at which oil was running out had begun thirty years earlier when he was part of a team assessing the world's oil resources for an American oil company. Later, when he was managing another oil firm, Fina, in Norway, he got that company to sponsor a similar assessment. “We used public reserve data, as I had not then appreciated how unreliable they were,” he says.

The results were published in a book, The Golden Century of Oil 1950-2050, in 1991. This led Petroconsultants, a company based in Geneva, to invite him to redo the study using their confidential, and much more reliable, oilfield data. Jean Laherrère, a former exploration manager for the French oil company Total who had developed some advanced analytical techniques, was also involved. Petroconsultants sold the report they produced for $50,000 a copy until it was suppressed as a result of pressure from a major US oil company which Campbell won't publicly name.

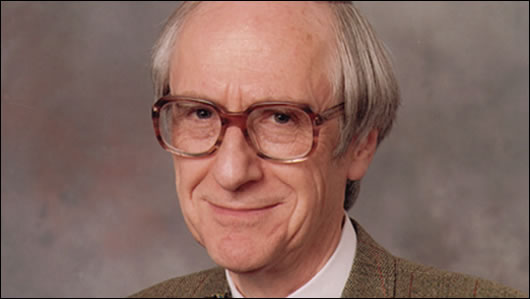

Dr Colin Campbell, who has carried out many studies into oil depletion

A coded message about oil supply limitations was included in the International Energy Agency’s 1998 World Energy Outlook report. “In effect the unidentified unconventional was a coded message for shortage” says Colin Campbell

However, Campbell published a summary of the report, The Coming Oil Crisis, in 1997. “The IEA purchased the book and contacted me, sending an analyst to spend a week going through the data,” he says. “It was evident that the team within the IEA working on the subject was fully convinced and saw its importance. They then produced a report for the G8 ministers' meeting in Moscow in March 1998. The text was bland enough but it contained a critical table showing that oil demand would outpace supply by 2010, save for the entry of an item called unidentified unconventional, whose supply rose to meet as much as 20 per cent of the world’s needs by 2020,” he says.

“Having managed to get it past the G8 ministers, the IEA team was able to include it in [its major annual report] the World Energy Outlook for 1998. In effect, the unidentified unconventional was a coded message for shortage.”

Campbell mentioned this to Dr David Fleming, an economist and one of Britain's leading thinkers on sustainability issues. Fleming wrote an article about the impending shortage for the April 1999 issue of Prospect magazine. “I sent a copy to the IEA and Fatih Birol rang me and said he wanted a meeting,” Fleming says. “We met at the Oxford and Cambridge Club. He said "You are right". He added that about six people round the world, as far as he was aware, had rumbled the [coded] message, and talked about assisting me with publicity in raising public awareness.”

Fatih Birol, the chief economist at the International Energy Agency and editor of the World Energy Outlook

But after Birol, who was then the head of the IEA's Economic Analysis Division and is now its chief economist and editor of the World Energy Outlook, returned to Paris “he went quiet” Fleming says. But the article was widely noted. It was re-printed in the Sunday Telegraph, summarised in The Week and Fleming was interviewed on the BBC radio's Today programme. “I sent the oil price up a dollar, I am told,” he says, “but I cannot really claim the credit [for breaking the story]. It came after hours of telephone tutorials with Colin Campbell.”

Campbell thinks that Birol did not maintain contact with Fleming because the IEA got into serious trouble with its masters in the OECD governments. “In the next issue of the World Energy Outlook, the unidentified unconventional became conventional non-OPEC, without comment or explanation,” he says.

David Fleming an economist whose commentary on oil shortages caused oil prices to rise by a dollar

Five years later, in December 2004, when I visited the IEA stand at the UN climate conference in Buenos Aires, I asked Cedric Philibert, the official responsible for developing its climate policies, about its attitude to the peak oil argument. “The good news is that there's enough oil to allow continued expansion for the next 30 years,” he said. I was shocked that he should call this “good news” at a climate conference.

Today's IEA line in relation to climate is very different. It is calling for large emissions cuts because “because a continuation of current trends in energy use puts the world on track for a rise in temperature of up to 6°C and poses serious threats to global energy security.”

Emissions cuts would also make any oil supply difficulties less severe. Over the past five years, Birol has been trying to quietly manoeuvre the organisation out of its increasingly untenable position that there's no looming shortage of oil. Its 2004 World Energy Outlook put the supply of oil in 2030 at 121 million barrels a day, a figure which led Christophe de Margerie, the then head of exploration for Total to comment “Numbers like 120 million barrels per day will never be reached, never.” The IEA reduced its estimate to 116 million in 2006 and to 105 in the edition that appeared last November.

The explanations the IEA has beenm offering on why the supply that it anticipated in earlier years might not, in fact, be available amount to saying that “the oil will be available if oil companies invest enough in developing new fields” and “Western oil companies need to be allowed to exploit fields in countries in which only national oil companies can currently operate.”

Unfortunately, because it does not wish to reveal that it has been publishing false supply projections since 1999, the IEA's recent warnings have not been as strident as they need to be to get politicians to change their policies. It was only last month (December 2009) that Birol actually stated clearly in an on-the-record interview that “the output of conventional oil will peak in 2020 if oil demand grows on a business-as-usual basis”. A year earlier, The Guardian's George Monbiot had to chase him all round the houses to get him to say that non-OPEC oil production would level off in “three-four years' time” and that if OPEC continued to invest, “we still expect that it will come around 2020 to a plateau.” The difference between a peak and a plateau is significant because a peak, of course, implies a subsequent decline. A plateau might persist for years before a decline begins.

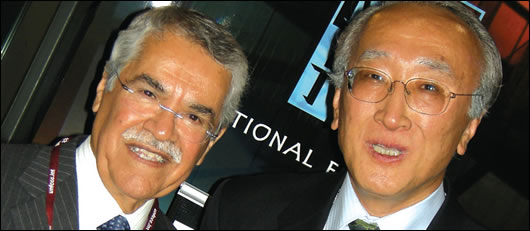

(left) Total chief executive Christophe de Margerie; (right) Kjell Aleklett, co-founder, along with Colin Campbell, of ASPO, the Association for the Study of Peak Oil

The biggest change in the IEA's message came at the end of 2008 when it published a report that revealed that the decline in oil production in 600 existing fields was running at 6.7 per cent a year compared to the 3.7 per cent decline it had estimated in 2007. Birol has also stated that the equivalent of four new Saudi Arabias would need to be discovered and put into production by 2030 merely to maintain current supply levels, and a further two would be needed to meet the expected increase in demand.

In fact, many oil watchers believe that the production of conventional (in other words easily extracted) oil peaked in 2005 and the shortfall is being made good by expensively-produced oil mainly from deepwater fields and the Canadian tar sands. As a result, they believe the IEA is still pretending that things are much better than they really are.

Kjell Aleklett, who co-founded the Association for the Study of Peak Oil, Aspo, with Colin Campbell, runs the Global Energy Systems Group at Uppsala University in Sweden where he is professor of physics. He describes the IEA's 2008 World Energy Outlook as a "political document" developed for consuming countries with a vested interest in low prices. His group has just released a careful analysis of the assumptions underlying its estimates. It concludes that crude oil production is more likely to be 75m barrels a day by 2030 than the "unrealistic" 105m projected by the IEA.

On the other hand, a US consultancy, IHS Cambridge Energy Research Associates, which rejects the peak oil concept entirely, published its own report,“The future of global oil supplies: understanding the building blocks,” in early November. This says that oil supplies could reach 115 million barrels a day around 2030, up from 92 million barrels today. They will remain at that level at least until 2050, the report says – in other words, a 20-year plateau.

The IHS report rejects the IEA's finding that the average oil field decline rate is 6.7 per cent and puts the figure at 4.5 per cent instead. It points out that 60 per cent of world production still comes from 548 giant fields and that “assertions that [these] giant oil fields are past their prime simply are not borne out in a recent detailed study.” Moreover, “some 76 giant fields, representing 84 billion barrels, remain undeveloped. Fields in general and giant fields in particular still show considerable potential for reserves upgrades.” It concludes that the output from these fields will not suddenly plummet and that “the world’s oil endowment is much bigger than many estimates about peak oil allow for.” As a result, there is plenty of oil left and future oil production will be mostly driven by the “above ground elements of the equation.” In other words, there needs to be adequate investment.

So what's a poor politician to do? Whom should he or she believe? The IEA, an organisation set up by oil consuming countries to provide information to use in their negotiations with OPEC and which is still downplaying the reality of depletion for fear of strengthening OPEC's hand? A specialist research group at a Swedish university? Or a gung-ho American consultancy?

The answer is simple, of course. It is to adopt the precautionary principle. Apart from the US study, every report that has come out recently has said that total world oil output will begin to decline between now and 2020 and that prices will rise significantly. In Britain, for example, there have been two recent reports. One, from the government-funded Energy Research Centre in October said worldwide production of conventionally extracted oil could "peak" and go into terminal decline before 2020 and that the British government was not facing up to the risk.

Another, by the Industry Taskforce on Peak Oil and Energy Security concluded that oil capacity will plateau between 2011 and 2015. Its members, which include Arup and Virgin, fear that "economic dislocation" is likely once the world wakes up to the potential for shortages and the price of oil races back up. They point out that the world's big recessions tend to have been generated at least in part by sudden escalations in energy costs.

"The risks to UK society from peak oil are far greater than those that tend to occupy the government's risk thinking, including terrorism," says Will Whitehorn of Virgin. "We fear this is because of over-estimation of reserves by the global oil industry, underinvestment in exploration and production, or a combination of the two."

The IEA has similar worries. The 2009 World Energy Outlook identifies higher oil prices, coupled with the downturn in oil sector investment, as a serious threat to the world economy. “As a result of the financial crisis, investment in upstream oil and gas has already been cut by over $90 billion this year compared with 2008,” it said in a press release in November. The release talks of an “increasing susceptibility to energy price spikes” and of “a persistently high level of spending on oil and gas imports” representing “a substantial financial burden on import-dependent consumers”.

Günther Oettinger, who is nominated to become the new energy commissioner for the EU

The Oil Depletion Analysis Centre believes that as the world economy emerges from recession, the oil price will rise to reflect the inadequate supply and push the economy back into a fresh decline. “This cycle will keep repeating. A permanent economic stagnation would then ensue. The public will not understand why nothing was done,” it says.

So what is happening in Ireland? Have attitudes changed because of The Guardian's story or the steady shift in the IEA's position? Energy minister Eamon Ryan needs no convincing about the threat presented by oil peak as he organised public meetings on the issue before he joined the government. But is any sense of urgency getting through to his Fianna Fáil colleagues?

“The political time horizon is very short,” he told Construct Ireland. “People paid attention when the oil price reached $145 a barrel but thought “That's that over with” when it dropped back to $40. But now the price is rising again.”

The outcome of the Copenhagen climate conference was “hugely disappointing” as he was hoping for an agreement on emissions reductions which would have sent “a strong signal to the business community”. What the world got instead was the Copenhagen Accord which set no targets and which was “noted” rather than endorsed by the global community. “Nobody knows what 'noted' means” he commented, “It's so weak a position that it may be impossible to build on the inspection and transparency commitments the Accord contains.”

The problem in Ireland was that climate change was not centre-stage in the public's mind. “The leak of the e-mails from the Climate Research Group was very sinister, and the present cold weather is not helping.”

IEA executive director Nobuo Tanaka caught up with Ali bin Ibrahim Al-Naimi, Saudi Arabian Minister of Petroleum and Mineral Resources, while in Poznan for the UN Climate Change Conference on 11 December. The two men reiterated their desire to see ongoing cooperation between OPEC and the IEA

Nevertheless, when asked whether any of his projects and proposals had failed to win support from the cabinet because other members did not appreciate the urgent necessity to deal with oil peak and climate change, he did not mention any. “I've been asked to provide estimates of future oil prices to NAMA because they want to take likely transport costs into account when they carry out site valuations,” he said.

His long-term strategy was to make Ireland a renewable electricity exporter using the undersea “supergrid” being discussed by ministers from Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom as well as Ireland. The ministers agreed to examine the feasibility of this e30 billion grid, which would be primarily for offshore wind energy grid, when they met in Brussels in early December. It incorporates the Isles (Irish Scottish Links on Energy Study) project which will examine the feasibility of the construction of an offshore electricity transmission network linking potential offshore sites for the generation of renewable energy in the coastal waters of Ireland, Northern Ireland and Western Scotland. The final Isles report, which is costing e2 million, is expected at the end of next year.

“Progress on the bigger project depends a lot on the new energy commissioner. The retiring commissioner, Andris Piebalgs has been excellent. I hope the new man, Günther Oettinger, who has still to be approved by the European Parliament, will be as strong in his support for renewable energy,” Minister Ryan said.

- Articles

- Oil Peak

- Peak timing

- emissions

- Birol

- OPEC

- ASPO

- Industry Taskforce on Peak Oil and Energy Security

Related items

-

Much ado about nothing

Much ado about nothing -

Decarbonising buildings “most important issue” – Climate Change Committee

Decarbonising buildings “most important issue” – Climate Change Committee -

Techrete aims for net zero carbon by 2030

Techrete aims for net zero carbon by 2030 -

Campaign launched to tackle whole-life environmental impact of buildings

Campaign launched to tackle whole-life environmental impact of buildings -

Heating emissions increase as Ireland falls short on decarbonisation

Heating emissions increase as Ireland falls short on decarbonisation -

Draft new Part L energy efficiency regulations “disappointing”, critics say

Draft new Part L energy efficiency regulations “disappointing”, critics say -

New research finds air pollution particles in human placentas

New research finds air pollution particles in human placentas -

A brave new world: Oil and architecture

A brave new world: Oil and architecture -

Policy for zero, or zero policy?

Policy for zero, or zero policy? -

UN advocates passive house in latest carbon emissions report

UN advocates passive house in latest carbon emissions report -

Who needs retrofit standards?

Who needs retrofit standards? -

It’s in Ireland’s interest to tackle climate change — EPA director general

It’s in Ireland’s interest to tackle climate change — EPA director general