- Eco Housing

- Posted

Green Town

As of 2006 there is more and more talk in Ireland about the house of tomorrow and some very progressive houses have been built that go far beyond the basic legislative requirements for modern housing. Among them is Baile Glas, a development of twelve social and affordable housing units in Lombardstown, County Cork, initiated by the Blackwater Resource Development Agency and Cork County Council. Construct Ireland’s Jason Walsh finds out more.

Social housing has a mixed reputation: clearly there is a need for low cost housing and Ireland has seen major redevelopment and improvements in the area in the last few years, but the reputation of the inner city sink estate still holds in the public mind. Developments like Baile Glas— or Green Town in English--may just change that perception altogether.

Social architecture

Designed to be as sustainable as possible as well as to foster community development, the twelve timber frame houses of Baile Glas are at the vanguard of social housing development in Ireland. Architecturally, the buildings adhere to planning requirements specifying vernacular design while also appearing progressive and open, referencing the modern.

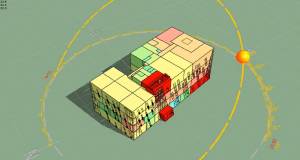

The design is informed by two principle sets of guidelines: the Cork rural design guide and Cepheus Passive House targets. The Cork Rural Design Guide emphasises design that is appropriate to local context and the Cepheus (Cost Efficient Passive Houses as European Standard) targets aim to minimise domestic energy use and losses. The Baile Glas project was awarded a Sustainable Energy Ireland grant under the House of Tomorrow Scheme.

"They're quite vernacular with pitched roofs and barge walls. We did look to the Cork rural development guidelines," says Philip Crowe, director of architecture at MCO Projects, the development's designer. "If they look modern it's because they have a lot of glazing."

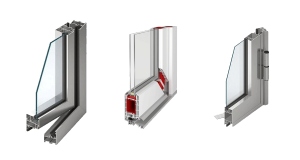

Of course, the glazing is not simply there for aesthetic reasons, although it does give the houses main elevation a striking look. Central to the large glazed fronts is the desire to maximise passive solar gain, pre-heating the air as it enters the houses.

"The first thing to say [about the glazing] is that they have a relatively large amount to the south and a minimal amount to the north."

Interestingly, this is not the sole measure taken to maximise passive heating: the houses' main elevation actually lies behind a glass layer, thus creating a 'winter garden': "It's like a double two levels of conservatory," says Crowe.

Architecturally, the buildings adhere to planning requirements specifying vernacular design while also appearing progressive and open, referencing the modern

This winter garden creates and traps most of the heat required in the house. The main living space is located behind the winter garden and in front of heat producing rooms such as the bathroom, kitchen and storage and utility rooms that are located on the north side of the buildings. This means that the main living areas are effectively located between two buffer zones which stabilise and control the temperature in the area.

Additionally, surplus heat requirements are satisfied by means of a heat pump with a high coefficient of performance. The principle is a simple one: heat exists in all air with a temperature above thermodynamic absolute zero (minus 273.15 °C). The heat pump works by taking the heat from the air, compressing its volume and moving it to other areas where the need is greater.

"It's mainly extracted from the winter garden," says MCO's Catriona Cantwell. "It traps heat and re-uses it for underfloor heating. Because the house is so well insulated it will never be cold," she says.

The houses' main elevation actually lies behind a glass layer, thus creating a 'winter garden', which creates and trapsmost of the heat required in the house

"The buffer zones keep the the heat in," says Philip Crowe. The end result is that the houses require virtually no space heating, with any additional heat requirements, particularly in the winter months, serviced by the underfloor system. It is predicted that Baile Glas will achieve a 60 per cent reduction in heat energy usage compared to typical new houses. In addition to underfloor heating on the ground floor there are low surface temperature radiators on the first floor.

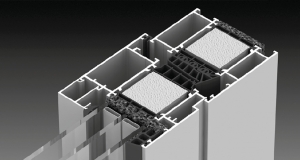

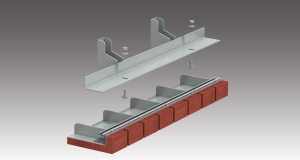

Of course, this would not be sufficient were it not for the buildings' high performance insulation. The ground floor in each building is a highly insulated (100 mm) concrete slab which acts as a thermal heat sink, retaining heat energy. The slab is designed to achieve a U-value of 0.17 W/m2K, thus outperforming Part L of the Building Regulations – TGD L 2006 – which require a U-value of 0.37 W/m2K if using the Overall Heat Loss method.

The walls have 2 layers of insulation: 90 mm between studs and 50 mm to the inside of the structure; with an overall U-value of 0.14 W/m2K (TGD L 2006 requires a U-value of 0.37 W/m2K). The internal stud walls are slabbed with high density Fermacell fibreboard, which removes the need for plastering and therefore reduces the use of cement based products and construction costs further.

Good insulation is also present in the ceilings: the pitched roofs are insulated above the ceilings to achieve an overall U-value of 0.12 W/m2K. (TGD L 2006 requires a U-value of 0.25 W/M2K).

"The other thing [about the design of the buildings] is that they don't have any protrusions – they're a perfect rectangle – this reduces the surface area," says Crowe.

"The first things you have to get right are insulation, airtightness and passive ventilation. If you have lots of angles you have more opportunity for poor fitting. The first issue in insulation is specification but the second is installation, which is often very poor on many sites," he says.

All of the windows, meanwhile, are argon filled double glazed units in timber frames using low emissivity glass.

Crowe is keen to point out that Baile Glas is not about expensive high tech solutions: "There's no point having lots of solar panels and wind turbines if you're not keeping what you're creating in the building," he says.

Indeed, Catriona Cantwell points out that the cost of the development is on par with more traditionally built social housing schemes – sustainability has been created at no cost through intelligent planning, design and specification.

For example, further reductions in heating requirements were made by design: the houses are terraced blocks.

"The fact that they're terraced is relatively unusual in rural developments today," says Crowe, going on to point out that there is no reason for any planning aversion to terraces: "It's not just an urban form and it's efficient in terms of minimising your footprint and surfaces."

Surplus heat requirements are satisfied by means of a heat pump with a high coefficient of performance

In keeping with the desire to promote a sense of community all of the houses, while south facing, are arranged around a communal space that also addresses the existing houses. A children's playground has been built and a community centre is in the planning stages.

"The real challenge in Lombardstown is for us to have it interact with the town and not become a place apart," he says.

"Another way it is socially sustainable is that the two bed units can be converted to three bed. [Also] Parking is kept away from the houses. That means you can be confident to let children play without worrying about traffic."

Catriona Cantwell points out that even the playground makes use of environmentally responsible materials: "The wooden components are from sustainable sources and the safety components are made from recycled tyres. We carefully researched that," she says.

The houses themselves are timber framed but do make use of some concrete: "You need to have thermal mass," says Crowe. "The easiest way to get it is to use concrete.” The outer leaf of the walls is masonry in line with the Department of the Environment requirements.

The houses are all timber framed with a masonry outerleaf. Timber frame construction was chosen because of speed of erection on site and quality control. Insulation between the timber structure is fitted off site under controlled conditions. this will have a dramatic effect on the as-built thermal performance of the houses

Outside, hard surfaces are minimised in favour of soft surfaces which encourages natural drainage and reduces the amount of water run off to drains. There is also recycling of water externally for the gardens and for car-washing.

Even street lighting has been approached in a new and innovative fashion at Baile Glas: in an unusually forward looking move, MCO Projects has organised a trial of street lights powered by wind and solar energy alongside standard lamps, which will operate entirely independently of the national grid.

Central to the large glazed fronts is the desire to maximise passive solar gain, preheating the air as it enters the house

Despite all of the innovation and use of what many would consider to be 'non-standard' materials, the entire development's budget is on a par with that of standard social housing in Ireland. Crowe predicts that greater use could further reduce costs: "The more these products are used, the more competitive they will become." Even the project's timeframe has been manageable, starting in November 2005 and due to end in mid-October 2006.

Community living

Beyond environmental sustainability there was also a need to think in terms of social sustainability. To kick start the project, Baile Glas received funding of €840,000 from the European Leader Fund for Rural Development, the biggest single Leader Fund award in Europe to date.

Tom Sheehan, a local councillor and chairman of Blackwater Resource Development explains that Baile Glas was not originally intended to be a local authority housing development: "A year or fifteen months ago at a board meeting, it struck me that €840,000 was not going to build the houses.

"We talked to the county council to see if they'd get involved and they did. Nothing would have been worse than to get halfway or two thirds of the way in and not know what to do," he says.

As it happens, Cork County Council was happy to get on board with the project and so a pioneering social and environmental housing development was born: "It's probably the first of its kind to be done by a local authority," says Sheehan. "There have been a number of [similar] private developments.

"The county council are enthusiastic for it and see it as a flagship."

For Blackwater Resource Development the issues of environmental and social sustainability dovetail neatly: "Environmental and energy [concerns] are major issues within the community now. We wanted to show how it could work in a small rural situation.

"The decline of rural Ireland is due to the decline of agriculture – we set out to counter that. We're trying to make sure rural Ireland retains a soul and a heart," says Sheehan.

When questioned as to whether Ireland's Leinster-centric development has been detrimental to rural areas, particularly in the west, Sheehan is reflective: "It's easy for us to agree with that but it's very much a National Spatial Strategy issue. We have to play a role ourselves to pull things in," he says.

"There is a quality of life out here that is significant. We're lucky in a sense that we're not living in large estates. We have good schools, public transport is improving all the time and we have GAA clubs, soccer clubs and golf clubs.

"Villages do need development to sustain them in the future – they need a critical mass of people to get banks, credit unions, garda stations and so on."

Similarly, the environmental credentials of the buildings at Baile Glas were central to the development for Blackwater. Ultimately, meeting the needs and desires of the future residents was as important an issue when it came to the sustainability as it was with the social aspects of the development: "It will be totally integrated in terms of energy use and environmental factors,” Sheehan says. “They are faced south to maximise solar energy. The backs face a public road and look quite like other houses.

"We don't want to re-invent the wheel or dream up harebrained schemes. However, we have some very forward looking communities in our catchment area," he says.

Blackwater Resource Development Agency is also looking to sustainable development in areas outside of building. For example, the group is currently involved in a study to ascertain whether a disused beet factory can be used to manufacture bio-ethanol and there are already cultivation trials of pennistum purpureum – better known as 'elephant grass' – another well-known bio-fuel crop.

Clearly the Blackwater group's interest in creating sustainable communities has been the catalyst for the entire Baile Glas development – something that Philip Crowe of MCO Projects understands and has designed to meet the group's expectations: "We weren't trying to do anything radical, we were trying to develop neat, well-detailed houses," says Crowe. It would appear that they have succeeded.

Photos and Rendering courtesy of MCO

- Articles

- Eco Housing

- Green Town

- house of tomorrow

- blackwater

- social architecture

- baile glas

- Green Town

- MCO

- timberframe

- solar gain

- thermal performance

Related items

-

Social skills - The A1 rapid build council homes that are sustainability all-rounders

Social skills - The A1 rapid build council homes that are sustainability all-rounders -

Buildings need better overheating models to guarantee future comfort

Buildings need better overheating models to guarantee future comfort -

Hi-therm+ wins construction product of the year

Hi-therm+ wins construction product of the year -

Kingspan launches new lower lambda Kooltherm range

Kingspan launches new lower lambda Kooltherm range -

Chiswick Eco Lodge stitches into historic London street

Chiswick Eco Lodge stitches into historic London street -

Ultimate Windows launches Olympia HI window

Ultimate Windows launches Olympia HI window -

Marmox Thermoblock features in high profile Leicester Square retrofit

Marmox Thermoblock features in high profile Leicester Square retrofit -

Isle of Wight development goes passive against the odds

Isle of Wight development goes passive against the odds -

Isover Vario delivers airtightness at nursing home extension

Isover Vario delivers airtightness at nursing home extension -

Ultimate Windows & Doors launches budget-friendly low energy range

Ultimate Windows & Doors launches budget-friendly low energy range -

Ancon to launch new products at Ecobuild 2016

Ancon to launch new products at Ecobuild 2016 -

Detail & workmanship key to cavity wall passive houses — Pat Doran

Detail & workmanship key to cavity wall passive houses — Pat Doran