- Blogs

- Posted

Three books and a taxi ride

Peter Rickaby looks back on an extraordinary career, the challenge of convincing people of the need for a new approach to buildings, and the people who helped him to do just that.

This article was originally published in issue 49 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

When I retired in 2023, this magazine’s editor thought it might be interesting if I wrote a retrospective of my forty years as an energy and sustainability consultant in the UK. At first I worried doing so might seem a little self-indulgent, but reflecting on those years, I realised that they weren’t about me, and that telling a little of the story was really a way of acknowledging the many, many people who have supported my work in many, many ways. And so, here it is…

One afternoon in the early 2000s, I was in a Dublin taxi with Linn Rafferty of National Energy Services. We had both been deeply involved in the development of domestic energy rating (the NHER and the SAP) in the UK, and we were in Dublin to assist SEI (now SEAI) with the development of the Irish equivalent – the DEAP.

Having established we were there on business, the driver asked us what we did.

“We are saving the world,’ Linn replied.

After a short pause, the driver said: “Thank you very much”.

At this point I felt the need to intervene: “Don’t thank us yet,” I said, “we are not very good at it”.

For me, this summed-up my career up to that point. I had spent twenty years mostly failing to persuade a reluctant industry and complacent politicians to take the challenge of climate change seriously, and to make buildings more energy efficient.

The early days of a better nation

Thirty years earlier, in 1971, while I was a first-year architecture undergraduate at Cambridge University, I took home for my Christmas vacation the book Population Resources Environment: Issues in Human Ecology by Paul and Anne Ehrlich. That book changed the direction of my studies and my career, and led me to other books such as E.F. Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered, the Club of Rome Report, Victor Olgyay’s Design with Climate, and many more.

It also raised a question that has remained with me ever since: however beautiful a building might be, how can it be great architecture if it does not perform efficiently and is not sustainable? I designed a few buildings with Robert Thompson that tried to address that question.

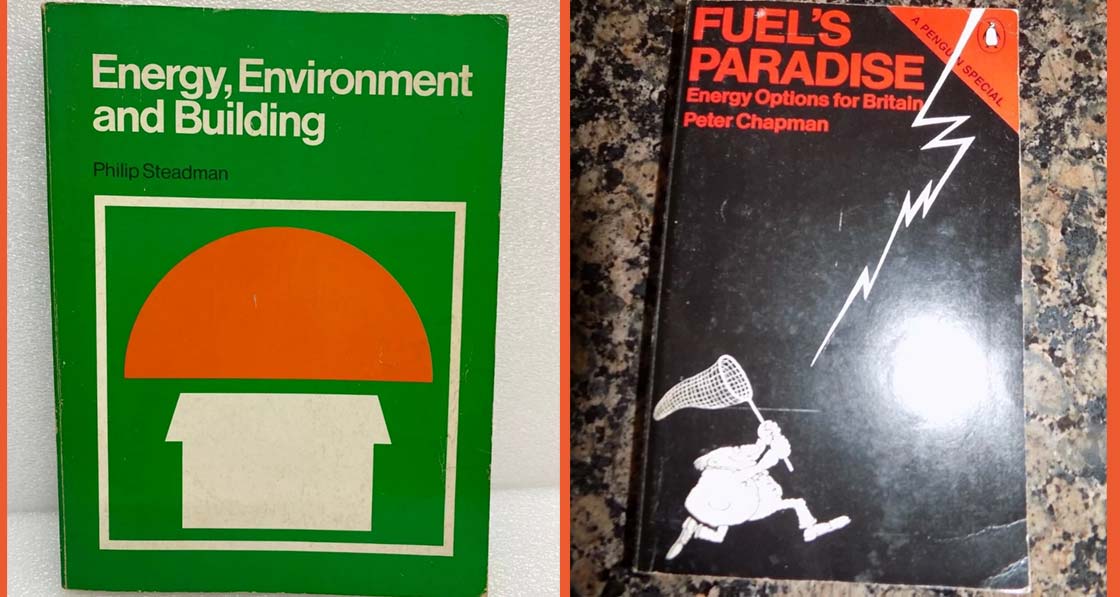

In 1973, Philip Steadman became my third-year undergraduate supervisor, and I spent my Christmas break that year drawing the illustrations for his ground-breaking book Energy, Environment and Building, which went on to become a best-seller for Cambridge University Press in the US.

The book was the first UK publication on that topic, and it explored pioneering US research and experimentation with energy efficient buildings.

Philip subsequently became my postgraduate diploma supervisor at Cambridge, and then my doctoral research supervisor at the Open University, where we worked together on energy related aspects of city-regional settlement patterns, using Tomas de la Barra’s integrated land-use and transport model TRANUS.

Later, Tomas and I built a planning model of the Inverness region for the Highland Council, and another for a city region in northern Norway. I went on to work with Philip for ten years on the UK’s national non-domestic building stock (NDBS) database, which is now housed at University College London (where Philip is an emeritus professor) and is being further developed to support UK Government retrofit policy. Altogether I worked with him for twenty-five years, during which time he taught me how to think and how to write, and I am immensely grateful to him for those lessons.

Two formative titles

Striking out

While at the Open University in the 1980s I also received my first consultancy commission. It was from John Doggart, who was working on energy efficiency for Milton Keynes Development Corporation (later he joined ECD). He asked me to review the planning and transport strategy for Milton Keynes with a view to making it more sustainable.

My report suggested moving the local centres from the middle of each estate to shared sites at the edges, reconfiguring the ‘grid square’ estates in linear, cruciform patterns to connect the local centres, provide sheltered walking routes and support public transport, and running the buses through the estates instead of on the pedestrian-free, high-speed city grid roads.

The project was a disaster.

My proposals had support from within MKDC but were opposed by the management, who perceived them as undermining their work. As a result, the report was embargoed to four copies only – one of which I still have. It was not an auspicious start, but some of the later development of Milton Keynes did follow my suggestions.

You can fuel all of the people some of the time. You can fuel some of the people all of the time. But you cannot fuel all of the people all of the time.

At around the same time, I read the third book to which the title of this piece refers: Fuel’s Paradise by Peter F. Chapman (subsequently known as Jake Chapman), a slim paperback published in 1976 that started with the aphorism: Fuel’s Paradise predicted climate change as a consequence of carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of fossil fuels – the first time that I encountered the idea.

Jake was then a professor at the Open University and leading the renowned Energy Research Group. He invited me to a week-long workshop during which fifteen of us hammered out the details of the UK’s National Home Energy Rating (NHER) scheme.

Subsequently, as a member of the NHER training consortium, I helped to train more than a thousand NHER and SAP energy rating assessors in the UK, and several dozen DEAP assessors in Ireland. Jake, and another member of that group of fifteen, John Willoughby, taught me most of what I know about energy efficiency in housing and how to improve it. John, a brilliant trainer, also showed me how to teach it.

Throughout the 1990s, I worked with John and many others in the housing Energy Efficiency Best Practice programme run first by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) then later by the Energy Saving Trust (EST). My small consultancy company Rickaby Thompson Associates also delivered energy consultancy based on thousands of energy rating assessments for housebuilders and architects.

An early green building project by Rickaby Thompson, the 2002 Environment Centre in High Wycombe

After the then Department of the Environment published Energy Efficiency in Council Housing (a resource pack and guide written by another of the fifteen, Dyfrig Hughes), we also started advising housing organisations about how to improve the energy efficiency of their stocks. A memorable project at that time was scoping and helping to deliver the EST’s Managed Housing programme, working with Alan Pither.

In the early 2000s we started writing technical guides to energy efficiency in buildings and housing: for the EST, the RIBA (with Bill Gething), the Construction Products Association (with John Willoughby, Liz Warren and Chloe McLaren Webb), the National Housing Federation (NHF, with a team from Savills) and the National Housing Maintenance Forum (NHMF, with Andrew Burke).

The most comprehensive guidance we produced was the set of twelve low carbon domestic retrofit guides, which I edited for the Institute for Sustainability, and whose authors included almost everyone I had worked with in the previous decade.

But these were still our ‘crying in the wilderness years’. By then we knew what needed to be done, but we couldn’t persuade the industry to do it, nor the government to legislate for it.

That began to change shortly after that taxi ride in Dublin.

In 2009, Kerry Mashford, then working for Technology Strategy Board (now Innovate UK) launched the Retrofit for the Future programme, which involved the funded deep retrofit of 115 houses for 86 housing associations, to a challenging performance standard (maximum GHG emissions 17 kgCO2e/m2/ yr), all fully monitored and evaluated over a two year period.

Having worked on two projects, for Peabody and for Places for People, delivered forty post construction reviews and observed several post-occupancy evaluations, I joined the evaluation panel, which provided a unique opportunity to learn and consolidate retrofit lessons from the programme.

Around that time, David Pierpoint asked me to help him deliver the annual Retro Expo exhibition and conference, for which I agreed to develop the technical content. When David became chief executive of the EU-funded Centre of Refurbishment Excellence (CoRE), I joined the board, and we set up the CoRE Fellowship. We also used the lessons from Retrofit for the Future as the basis of a systematic approach to retrofit risks pioneered for the London RE:NEW programme by another CoRE Fellow, Lisa Pasquale.

Also at CoRE, Robert Prewett and Mark Elton conceived the role of the retrofit coordinator, and with others we developed an acclaimed retrofit coordinator training course and delivered it nationwide. Despite the malicious take-down of CoRE by Stoke-on-Trent Council, that course is still the basis of the Retrofit Academy’s Retrofit Coordinator training, ten years later, and thousands have gained the qualification.

An early green building project by Rickaby Thompson, the 2002 Environment Centre in High Wycombe

By 2015, despite the earlier failure of the government’s ill-conceived Green Deal retrofit scheme, measures-based domestic retrofit was beginning to happen in the UK, especially through the Energy Company Obligation (ECO), Community Energy Reduction Target (CERT) and Community Energy Saving Programme (CESP), all government promoted.

However, a constellation of installation companies that had grown up – and grown rich – from earlier ‘supplier obligation’ fuel poverty schemes were doing damage both to homes and to occupants’ health through a combination of incompetence, ignorance of retrofit risks, ingrained poor practice, and carelessness.

Serious retrofit failures occurred in north and south Wales and in Scotland, culminating in the disastrous Fishwick external insulation scheme in Preston in 2013 and the Grenfell Tower tragedy in 2017.

In the face of widespread complaint and criticism, two government departments (BEIS and DCLG) initiated the Each Home Counts review, led by Peter Bonfield. Here was an opportunity to put into practice the lessons learned from Retrofit for the Future and consolidated at CoRE.

Having contributed to several of the Each Home Counts workstreams, I was approached by Clare Price of BSI, and we became the coleads of the technical standards workstream and members of the Each Home Counts implementation board. This was an experience of the politics of retrofit at first hand! In December 2016, the report of the Each Home Counts review was published, and in response to recommendations 8, 9 and 10 BSI commissioned research into retrofit standards from NEF, established the BSI Retrofit Standards Task Group (RSTG, which I chaired until 2023) and facilitated the development by the RSTG of the BSI Retrofit Standards Framework, a device intended to bring every current and relevant standard to bear on retrofit projects.

The retrofit installer standard PAS 2030 had existed since 2011, but early versions were widely held to be unfit for purpose. The RSTG promoted the upgrading of PAS 2030 in 2017 and 2019, and the development, by an industry steering group, of an overarching domestic retrofit standard, PAS 2035. I became the technical author of PAS 2030:2019, PAS 2035:2019 and the non-domestic retrofit standard PAS 2038:2021. In parallel, in response to recommendation 11 of the Each Home Counts review, the newly established Retrofit Academy led by David Pierpoint upgraded and formalised the domestic retrofit coordinator training course originally developed at CoRE.

The academy has since gone from strength to strength, now offers a wide range of online retrofit training courses at several levels and has become the UK’s leading retrofit training provider. Through thick and thin, David’s inspiring commitment to safe, quality retrofit has never wavered. While working on the Each Home Counts review, we were approached by my friend Nic Wedlake, who was then sustainability manager at Peabody. They had acquired with Gallions Housing the iconic Thamesmead Estate in southeast London (the setting for Stanley Kubrick’s dystopian film A Clockwork Orange).

The Thamesmead community was fuel poor, and the estate was riddled with condensation, damp and mould (CDM) – the worst I had seen in thirty years.

-

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

-

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

-

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

-

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

The Thamesmead estate, which suffered some of the worst incidences of mould Peter Rickaby encountered in his career, shown here prior to remedial work and after Aereco demand control ventilation systems were retrofitted

https://passivehouseplus.ie/blogs/three-books-and-a-taxi-ride#sigProIdcb2ae6ba63

We were asked to develop and deliver a strategy for dealing with it, especially in homes that Peabody would not be able to retrofit or redevelop for ten years or more.

This was the most challenging project we ever took on – but it had the potential to make a difference. We designed and implemented a ground-breaking, risk-based strategy that combined energy advice for every home (brilliantly delivered by Nadira Moreea), the Switchee smart heating controller (an IOT device that we also used for monitoring and evaluation) and a state-of-the-art demand-controlled, centralised mechanical extract ventilation system (DC cMEV) from Aereco.

Lots of lessons were learned: the importance of energy advice, the value of ventilation capacity, the effectiveness of continuous ventilation, the importance of it being silent, and the efficiency of demand-control.

Simon Jones and Peter King of Aereco taught me more about domestic ventilation in that project than I had learned in the previous thirty years. The outcome was that the mould was banished from Thamesmead and did not return, no ventilation systems were switched off or disabled by occupants, and the strategy won an NHMF award. I subsequently implemented similar strategies for the Northern Ireland Housing Executive and (with Nick Heath) for the London Borough of Southwark).

Beginning again

The Thamesmead community was fuel poor, and the estate was riddled with condensation, damp and mould – the worst I had seen in thirty years.

By 2017 I had tired of running a small consultancy, so we closed the company, and I took on three new part-time jobs. At the UK Centre for Moisture in Buildings, founded by the late, great Neil May and housed at UCL, I worked with Nick Heath, Valentina Marincioni and Robert Prewett to develop the twoday CPD course Understanding and Managing Moisture Risks in Buildings.

The course was licensed by UCL for delivery by CIBSE Training and the Property Care Association (PCA), and the PCA still presents the course online twice each year, using UKCB’s training team. Valentina taught me all I know about moisture in buildings, and Hector Altamirano-Medina taught me about mould. Subsequently, we developed a face-toface course about condensation, damp and mould (CDM) for housing organisations, and Hector has recently developed an expanded CDM course for UCL/UKCMB, to be presented online on the Future Learn platform.

I also spent nearly two years as part-time technical director of the Retrofit Academy, reviewing and updating the retrofit coordinator training course, writing technical guidance and coordinating a CPD programme of technical seminars and workshops for retrofit coordinators.

By this time, we were unravelling the complexities of complying with PAS 2030 and PAS 2035, and I joined several steering groups for technical guides written by Colin King and Sarah Price.

Finally, I joined Savills social housing team as a part-time retrofit consultant, collaborating first with John Kiely and later with John Barnes, David Prescott, Peter Oliver, Richard Rockman and Phil McRae.

This was the most professional and the friendliest team I ever worked with. John and Peter taught me how to help housing organisations integrate retrofit with stock condition surveys and with asset management and investment planning, and I worked with the others to improve their processes for delivering PAS 2035 compliant retrofit projects funded by the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund (SHDF).

I also wrote a comprehensive technical specification for domestic retrofit, for use in those projects. My former colleague at Rickaby Thomson Associates, Kathryn Derby, was also working for Savills, providing SAPbased retrofit improvement option evaluation. Kathryn has delivered thousands of IOEs, and by now she must be the most experienced domestic retrofit IOE consultant in the UK.

Back in the taxi, as we approached our destination, the driver asked: “So are you two like Bob Geldof? He was here yesterday to receive an honorary degree for saving the world”.

Quick as a flash, Linn responded: “Oh no, Bob Geldof just saves Africa, we’re saving the whole world”.

If only… Did my many colleagues and I make a difference? I don’t know.

The retrofit baton has now been passed to others – the impressively motivated and committed generation of building professionals who are transforming the retrofit industry via organisations like LETI, ACAN, the National Retrofit Hub and BE-ST in Scotland.

The rising stars are too numerous to list here, and I have great confidence that they will achieve their objectives, although less confidence that they will get the support they need from the government.

They are heroes, but I will leave my last words to a different kind of hero, Greta Thunberg: “No-one is too small to make a difference”.

About the author

Dr Peter Rickaby is now almost retired and lives with his wife and some of their grown-up children and grandchildren near Johannesburg in South Africa. Peter is an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at UCL and still works part-time for UKCMB and the Retrofit Academy. He is also working with rise international, a not-for-profit organisation that is researching and developing sustainable building materials for use in Lesotho, to promote sustainable development, entrepreneurship and employment. That work is part-funded by Irish Aid.