- Blogs

- Posted

Energy poverty and electric heating

As electricity decarbonises, the case for switching from fossil fuel boilers to efficient use of electricity to heat buildings via heat pumps has become overwhelming. But in markets like the UK where electricity is far more expensive than the European average, and people on low incomes may be chronically underheating poorly insulated homes, could a drive to electrify heating exacerbate energy poverty?

This article was originally published in issue 50 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

It is not, admittedly, that difficult to annoy me. But one sure way is to use the phrase “rebound effect”. This phrase implies disappointment that after energy retrofit, building occupants have exploited the improvements to bounce their temperatures up, so energy use falls less than the model predicted.

Are improvements in comfort and living conditions, for people who could previously never afford to keep properly warm, really a failure, to be regretted?

Perhaps one reason for this mis-categorisation of success as a kind of failure, is the long-standing conflation of “decarbonisation” – action to tackle emissions – with action to address fuel poverty and cold homes. They have never really been the same thing, but recent changes mean it is urgent that we recognise this explicitly.

For years, many home retrofit programmes have been run under the aegis of variously named agencies and departments with responsibility for energy and climate. Programmes established to reduce carbon emissions have also been used to address fuel poverty: in some, households with poor health or restricted income have been the only targeted beneficiaries.

When heating was pretty much all fossil fuel-based, this was a convenient elision, if not entirely an honest one. The demand reduction measures that used to form the bulk of decarbonisation programmes – insulation, draught-proofing, more efficient boilers – are also measures that would alleviate fuel poverty and improve living conditions. (There is a huge aside about ventilation provision here; air quality has been a serious casualty of the ‘two programmes one heading’ shorthand).

Yes, the comfort take meant that emissions did not always fall much, but nonetheless, people were being helped – so the work was worth doing.

But now there is a whole new, super-potent decarbonisation tool on the block. Thanks to the soaring levels of renewables on the grid, converting from fossil fuel to electric heating cuts emissions without a single roll of insulation being laid. With a heat pump, emissions can be reduced again, two, three or even four-fold.

In fact, heat pumps have become so effective at reducing emissions that some are questioning the need for anything beyond the most basic fabric improvements — something Toby Cambray wrote very eloquently about a few issues ago (please read it!)

But while electrification is indeed great news for the climate, whether it benefits the end user or not is a different question. Electricity remains far more expensive per kWh than gas in both the UK and Ireland. This means that decarbonisation of heating cannot in and of itself make living conditions easier for the most vulnerable.

We can, in other words, no longer pretend that decarbonisation and fuel poverty alleviation are one and the same thing.

When direct electric heating such as infrared panels or storage heaters are installed to replace fossil fuel heating, there is at least an understanding that fabric efficiency will have to improve, as everyone knows how expensive these systems are to run.

Heat pump installations are not always treated with the same caution, because the assumption is that they will, if anything, make bills lower. Heat pumps are certainly more efficient than direct electric heat, and even in the UK with its huge spark gap, modelling indicates that running a reasonably well set up heat pump should probably cost about the same as running a boiler on mains gas – or even less. And this can indeed be the case (it has been for me, for instance).

But heat pumps have a perversity about them that can undermine all the modelled assumptions. By a particularly cruel irony, the less heat you can afford, the more expensive that heat is likely to be. All of a sudden, there is a danger that decarbonisation programmes might exacerbate fuel poverty, not alleviate it.

The problem here is that the understanding of “a well-run heat pump” means it is running for 21 or 24 hours a day, and possibly using a smart tariff too. But this understanding excludes some of our most vulnerable households. People on very constrained budgets may feel quite unable to run a heat pump continuously.

They have never spent that much on heating and can’t begin to now. Because heat pump running costs are not being modelled with this reality in mind, we risk being blind to this.

Because of the non-linear physics involved in heat pump performance, running a heat pump for only a few hours per day can lead to extremely high costs per unit of heat, compared to gas. It can even lead to higher bills overall, even while there is less heat, overall, supplied into the home. This is a particular danger in the UK, with its very high electricity to gas price ratio.

Some low-income householders with newly installed heat pumps have run into real difficulties because of this. The situation can spiral as households cut back further, then see ever increasing costs of heat. At this point people may give up and resort to a single room heater instead.

So, what can we do? The most important thing is probably to recognise that while with fabric improvements, the modelled running cost savings can be more-or-less translated into increased affordability of warmth, this simply does not apply with a heat pump. The cost of heat actually depends on how much you are using. Hard to anticipate – for a householder, and for a policy maker too.

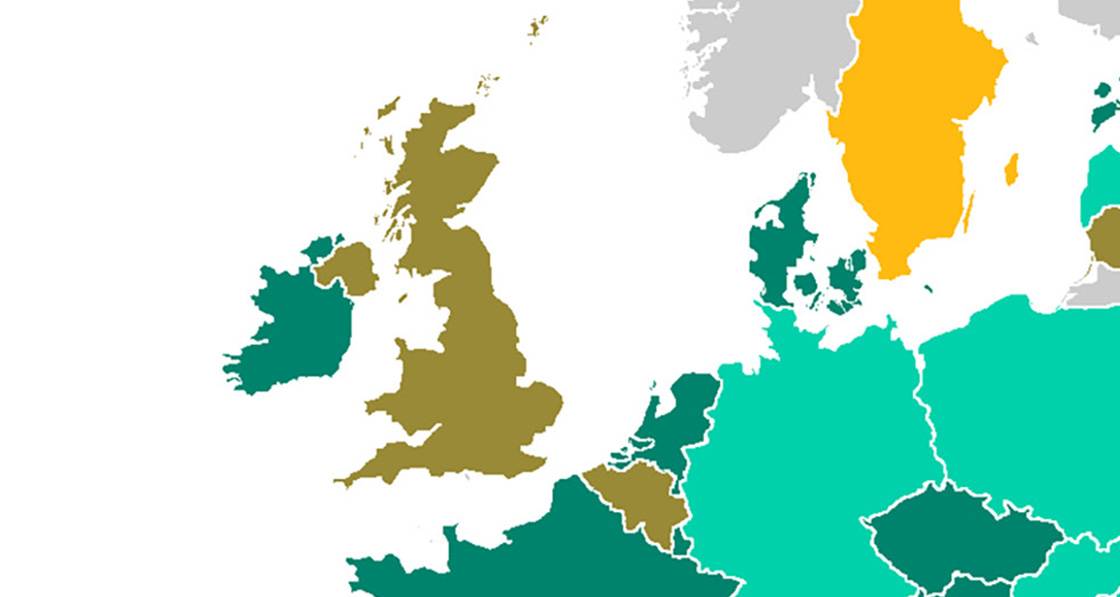

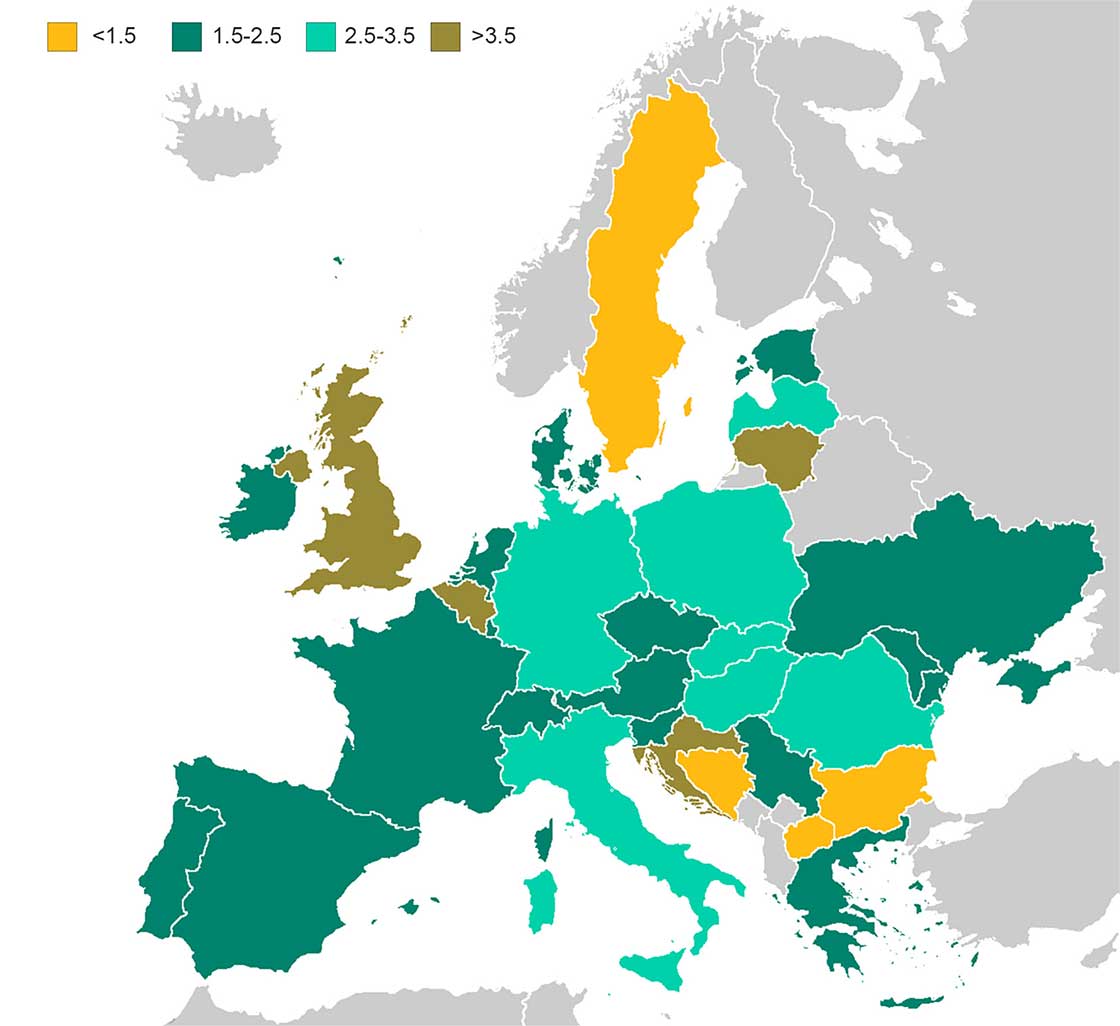

European electricity to gas price ratio. Source: Eurostat, using prices from first half of 2023. Credit: Rex Colley, adapted from EHPA.

We have to start “stress testing” running cost modelling against different budgets, different heating patterns, and different heating needs, before we can say “bills will not rise”.

We should also understand the air source heat pump ‘double winter penalty’, where due to lower coefficients of performance (COPs) in colder weather unit costs of heat are highest, just when you need most of it – and consider how this impacts households using credit meters.

We urgently need to work out how to make running heat pumps affordable, and, equally critically, predictable, in terms of money in versus comfort out, so people with financial constraints can be in control of their spending.

The fact that people have been running their heating for just an hour or two here and there was never acceptable. But if we continue to fool ourselves that “decarbonisation” will help them, the approach risks becoming catastrophic.

We must make electricity costs constant and predictable, and to make constant heat – even at a low level – an automatic part of living with a heat pump, whatever your income and resources.

When we provide excellent fabric, the problem effectively disappears (heat pump running costs do not seem to be an issue in Energiesprong retrofits or passive houses). If we can’t do that for everyone soon, then other ways must be found to protect the most vulnerable recipients of decarbonised heating. This might be a warm rent, a set price comfort guarantee, a heat-on-prescription model.

But the important thing is to make costs constant and predictable, and to make constant heat – even at a low level – an automatic part of living with a heat pump, whatever your income and resources.

This is where heat pumps might really come into their own. A steady, modest supply of heat from a well set up heat pump is one of the best ways to get a low unit cost of heat. Supporting this as part of decarbonisation would protect people’s health and wellbeing; it would protect buildings; it could even protect landlords’ rental incomes.

And it might even mean that fuel poverty alleviation and decarbonisation can work together again. Let’s just keep clear in our minds that they aren’t the same thing.