- Climate Change

- Posted

Climate control

As fears grow amongst climate scientists that the world may be close to reaching a tipping point leading to runaway global warming, there’s a growing recognition that the forthcoming UN climate conference in Copenhagen must deliver dramatic and binding targets to cut carbon. According to Richard Douthwaite, the talks are unlikely to deliver sufficiently meaningful action.

The choice is stark: either the governments of the world agree to engineer a planned energy descent or we will get a chaotic one by default which will cost hundreds of millions of lives. The decision between the two will be made at the UN climate conference in Copenhagen in December this year.

I'm fearful about the result because the politicians who will take the decision are not even aware that this is the choice they are making. Moreover, even if they were, it would be impossible for them to choose a planned approach immediately because no planning has been done and they are not facing up to the problem in an honest way.

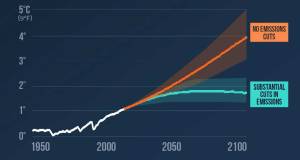

The leaders of the twenty big countries collectively responsible for 80 per cent of the world's greenhouse emissions have made a bad decision already. In July, at the Major Economies Forum in Italy, they agreed that the global average temperature should not rise by more than 2 degrees C above its level in pre-industrial times.

Actually agreeing a temperature target (what took them so long?) was a step forward but one that didn't go nearly far enough because every one of those leaders knew that a 2 degree rise would have extremely undesirable effects. It could even be enough to trigger positive feedbacks which set off a rapid, uncontrollable warming with catastrophic consequences.

We've only had a 0.7 degree rise so far and some of the feedbacks have already kicked in. For example, the unexpectedly rapid rate at which the Arctic ice has been melting has increased the rate at which the planet is warming, because the white ice which reflected solar energy back into space has been replaced by a dark, heat-absorbing sea. Similarly, the melting of the permafrost in Russia has released vast amounts of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere.

EU officials charged with climate policy development have become gravely alarmed by the reports of feedbacks they have been receiving. “Panic doesn't BEGIN to describe it” one of them told me in an e-mail. The capital letters are his. James Hansen, the director of NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies is also alarmed. The “elements of a perfect storm, a global cataclysm, are assembled” he told the US Congress last year.

So why didn't the 20 leaders opt for a lower, safer temperature target such as the 1.5 degrees limit demanded by 80 small, poor countries, including the small island states which will disappear under the waves because of rising sea levels? The answer is that the economic consequences of cutting fossil fuel use in the next few years by enough to limit the rise to 1.5 would inevitably bring their economies crashing down. The advantage of the 2 degree target is that it means that serious adjustments can be delayed at least until those involved are out of office.

The big-country leaders hope that the 2 degree target can be achieved by allowing the atmospheric concentration of CO2 to rise to 450 parts per million (ppmv) before it stabilises. This requires that global fossil emissions are cut by 80 per cent of their 2005 level by 2050, with the cut-backs beginning in 2012.

At the Italian meeting, the rich big countries undertook to make the 80 per cent cuts by 2050 but the poorer big countries like India, China and Brazil did not. They refused to commit to any cuts just yet on the basis that their people need to use more energy to lift themselves out of poverty. They urged the rich countries to cut by more than 80 per cent instead.

Most of the rich big countries are being guarded about when they will start making the cuts and how large their initial ones will be. The EU presents itself as an honourable exception. It has said that it will cut its emissions by 20 per cent of their 1990 level (that's 14 per cent of their 2005 level) by 2020 whatever happens, and will cut by 30 per cent of the 1990 rate (in other words, 21 per cent of 2005 emissions) if other rich countries agree to substantial cuts too.

But its offers are not what they seem. FERN, the Forests and the European Union Resource Network, an international NGO with offices in England, Holland and Belgium, calculated earlier this year that the European Commission was planning to make only a quarter of its 20 per cent pre-2020 emissions cut within the EU. The rest would be made by paying companies in developing countries to reduce their emissions instead. This is a practice called offsetting which is permitted under the Kyoto Protocol's Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). Unfortunately, carbon offsets do not help prevent climate change because they do not reduce overall emissions.

“Even in a best case scenario,” FERN points out, “all they can do is stabilise levels, because a reduction in one place justifies an extra emission in another place. Unfortunately, even this best-case scenario appears to be rare as it is not possible to verify whether any claimed reduction would otherwise have occurred. By allowing the release of extra emissions without the certainty of equivalent extra reductions elsewhere, any trading scheme involving carbon offsets may increase rather than reduce GHG emissions. On top of this, many of these projects also affect the rights of some of the world’s poorest communities, resulting in increased hardship and suffering.”

James Hansen, the director of NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies

Other rich countries can be expected to use offsets too and big developing countries like India and China are keen that they should do so because it brings in foreign exchange. The smaller poor countries which want the 1.5 degree target are free to demand it because they get no benefits from CDM. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, out of 18 CDM projects, 11 are in South Africa. There are three small electrification projects in Uganda, a large scheme to capture methane from a dump in Tanzania, two small plants recovering methane from waste water, one in the Central African Republic, the other in Nigeria, which also has a large scheme to prevent an Italian oil company flaring off natural gas. Not very impressive, but if you look at a map showing projects in India, China and Brazil, there are so many dots they merge into each other.

In view of this, the CDM has to be considered to be nothing more than a big-country you-scratch-my-back-I'll scratch-yours scam. Under it, the rich countries continue polluting and bribe big poor countries not to kick up a fuss. Global emissions are not reduced and smaller, poorer countries are ignored.

The existence of the CDM has enabled countries to avoid having to develop effective means of achieving rapid, substantial emissions cuts within their own borders. Feasta, an Irish NGO, has put forward Cap and Share as way of doing this but the idea has not been taken up. As result, some combination of cap and trade and a carbon tax are the only tools governments have available.

That's not good. The EU's version of cap and trade, the Emissions Trading System, has failed badly so far. In its first phase, from 2005-2008, it enabled the power producers to make massive profits at the expense of their customers and produced no reductions at all. In the current phase, 2009-2013, the price of the right to emit is so low that it's not worth anyone taking much trouble to avoid paying it. In any case, the ETS covers less than half of the EU's fossil emissions.

The Maldives, arguably the lowest-lying country in the world, could disappear under the waves due to rising sea levels

A carbon tax is a clunky solution because it cannot guarantee that the target emissions level will be met. The rate has to be adjusted up and down depending on fossil fuel prices and economic conditions to get the required reduction, and these constantly changing rates would make it a political football. “There's a lower rate in Britain and Germany. We can't compete against that.”

Ireland is planning to introduce a carbon tax in this December's budget to try to reduce emissions not covered by the ETS, such as those from road transport and heating fuels. A report last December commissioned by Comhar, the National Sustainable Development Council, showed that the tax might have to rise to e182 per tonne of CO2 to get non-ETS emissions down by enough to reach the 20 per cent target. That would add 42 cents to petrol's current price. If such a price rise was brought in overnight, imagine the outcry about the hardships to people living in rural areas and the damage to national competitiveness.

So, in the absence of suitable tools, the 450 target will not be easy to reach, and governments are coming to realise that they would have more wriggle-room if emissions from the way the land is used could be reduced. For example, if deforestation, the source of about 25 per cent of global emissions, was ended entirely by 2050, it would only be necessary to reduce the world's fossil fuel emissions to 55 per cent of their 2005 level by 2050 rather than by the 80 per cent, and they would not have to be reduced any further after that. Accordingly, one of the topics on the agenda for Copenhagen is REDD – Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation – which is all about rich countries continuing to emit and paying countries like Brazil, Central African Republic and Indonesia not to clear their trees as rapidly as they have been doing up to now.

But the real problem with the 450 target is that it does not guarantee that the world's average temperature will not rise by more than two degrees. You can see this for yourself by using C-LEARN, an easy-to-use climate model which is said to give results very close to those used by climate professionals. Just go to:

http://forio.com/simulation/climate-development/ and put your assumptions into the boxes on the screen. For example, if you assume that all parts of the world reduce their fossil emissions by 55 per cent by 2050 and deforestation has been halted by then too, you hit the 450 target.

The UN’s chief climate scientist, Rajendra Pachauri, believes that things are going to get substantially worse than anticipated

Professor John Schellnhuber, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany told The Guardian recently that even a small increase in temperature could trigger several climatic tipping points.

Unfortunately, though, the model shows that the Earth's temperature will be 2.6 degrees higher in 2100 than in pre-industrial times and, worse, it will still be rising. More sophisticated models indicate that there may be only a fifty-fifty chance of not exceeding the 2 degree target at the 450 ppm concentration. The Stern Review produced for the British government put the chance of staying below it at only 22 per cent.

This uncertainty about the temperature rise is inevitable since the atmosphere is a complex system and, as with all complex systems, it is impossible to state categorically how it will behave as a result of a change to one component, such as the concentration of a single gas. All climate modellers can hope to do, therefore, is to estimate the probability that the temperature rise will stay below the 2 degree figure at various concentrations. The lower the concentration, the higher the probability of staying below the limit will be.

It's the uncertainty that makes the 450 target unacceptable. The risks of exceeding a 2 degree rise are too great. As the Australian ecologist Philip Sutton says, we "wouldn't fly in a plane that had more than a 1 per cent chance of crashing. We should be at least as careful with the planet."

So let's go back to the C-LEARN model and plug in a 99 per cent drop in fossil emissions by 2050, a complete cessation of deforestation and a massive tree-planting drive to take up a billion tonnes of carbon a year (that's 3.7 billion tonnes of CO2, about a seventh of current fossil fuel emissions) from the air and see if we can hit the 2 degree target at the end of the century. The answer is that we can and we can also achieve an atmospheric concentration of 356ppmv by then. This is about 8 per cent less than the current concentration and the fall would continue as the years passed, bringing the temperature down to nearer its current level.

The fast-growing miscanthus, or elephant grass, can produce a high yield of biomass fuel

Rather than 450 ppmv a target of 350 ppmv or below is advocated by the smaller, poorer nations, by James Hansen and by the UN's chief climate scientist, Rajendra Pachauri. "As chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, I cannot take a position because we do not make recommendations," Pachauri told an AFP journalist this August when asked if he supported the 350 limit, “but as a human being I am fully supportive of that goal. What is happening, and what is likely to happen, convinces me that the world must be really ambitious and very determined at moving toward a 350 target." He added later in the interview that “things are going to get substantially worse than what we had anticipated."

When I spoke to Pachauri in Dublin in 2007, he told me that an increase of 1.5 degree C might be the upper limit of what is tolerable but I've been unable to find an estimate of the chances that 350 ppm would achieve that. Hansen supports the figure only as an interim target which would be re-assessed in the light of new data. He points out that the Arctic sea-ice began to melt decades ago and his presentations suggest that 300-325 ppm might be necessary for the ice to increase again.

Other scientists think that almost any increase over the pre-industrial level might be too much. Professor John Schellnhuber, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, told The Guardian recently that even a small increase in temperature could trigger several climatic tipping points.

“Nobody can say for sure that 330ppm is safe,’ he said. “Perhaps it will not matter whether we have 270ppm or 320ppm, but operating well outside the [historic] realm of carbon dioxide concentrations is risky as long as we have not fully understood the relevant feedback mechanisms.”

What all this means is that, for there to be any chance of maintaining a livable planet, fossil fuel emissions have to be reduced extremely rapidly and there needs to be a massive programme to use plants and the soils to get CO2 out of the air. The Copenhagen meeting will be a failure if it does not make it clear that both need to happen and fails to get time-tabled undertakings from governments to bring them about.

Extracting and burying some of the CO2 in the air is likely to prove the easier task, as it only takes a relatively small increase in the amount of carbon held in the soil and the plants growing on it to achieve the desired result. The UN Environmental Programme estimates that terrestrial ecosystems store about 600 billion tonnes of carbon in living organisms and decaying material and 1,500 billion tonnes in soil organic matter. The total, 2,100 billion tonnes, is almost three times the amount currently in the atmosphere. Consequently, reducing the atmospheric concentration of CO2 from 387 to 350 ppmv only involves increasing the amount in plants and soils by 3 per cent. Returning to a really safe level demands a 9 per cent increase.

Another encouraging fact is that each year's flow of carbon into and out of the terrestrial stock is huge. It is only necessary to reduce the outflow and/or increase the inflow by a small amount to achieve the 9 per cent increase over, say, the next fifty years. These are the figures: each year, plants take in roughly 120 billion tonnes of carbon from the air each year – about 19 times the amount released from fossil fuels – but about half of the amount they capture is released again when they respire at night, and a similar amount when they burn or decay.

(above) Farming land at Uamby, News South Wales in its original condition and (below) the same land once Holistic Management International’s land reclamation approach had been applied

The efforts of millions of people are going to be needed to save a habitable Earth and themselves. More trees is only part of the solution. Grazing land will be an important sink too and Allan Holistic Management International has achieved amazing results in Africa, Australia and the US by getting farmers to graze their paddocks really intensively and then take the stock right away until the grass has become tall again. HMI argues that continual grazing is damaging because, when the new, fresh leaves are nibbled away, the plants are denied the energy they need to develop strong, deep root systems – which of course put carbon below the ground.

“The fabulous thing about sequestering carbon in grasslands is that you can keep on doing it forever – you can keep building soil on soil on soil... perennial grasses can outlive their owners; they're longer-lived than a lot of trees” says Christine Jones, the founder of the Australian Soil Carbon Accreditation Scheme which has launched a pilot programme under which farmers are paid $90 for each tonne of carbon they get their plants to place in their soil.

I can see people getting very enthusiastic about getting carbon out of the air, but they are going to be much less keen on reducing fossil fuel emissions to near zero by 2050, because this will cut their fuel use by about 8 per cent a year. Although there is a close relationship between incomes and energy use, the only shred of comfort is that people's incomes will fall by less than 8 per cent thanks to efficiency gains and the rapid development of renewable power sources. Indeed, one of the most important renewable energy sources will be the biomass produced by the planting programme. For example, land growing miscanthus (elephant grass) can produce 20 tonnes of fuel per hectare a year and also lock up around 2.25 tonnes of carbon dioxide annually in its roots and the soil.

The fact that incomes will fall as fossil energy use is cut presents the world's leaders with an insurmountable political difficulty. To make such deep cuts tolerable they would need to know how to change their economic and social systems to cope, but none of them has thought about that. As a result, if 8 per cent cuts were actually made, their economic and monetary systems would collapse and there would be riots in the streets.

Our leaders' total failure to plan for a powerdown is the reason why they cannot and will not respond adequately to the climate crisis in Copenhagen this year. It will take a miracle to prove me wrong. I fervently hope one comes along.

- Articles

- Climate Change

- Climate control

- douthwaite

- Feasta

- Copenhagen conference

- temperature target

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- CLEARN

Related items

-

Property industry faces ‘triple threat’ from climate crisis

Property industry faces ‘triple threat’ from climate crisis -

Irish Green Building Council launch event to promote sustainable building practices

Irish Green Building Council launch event to promote sustainable building practices -

Ashden Awards winners showcase climate solutions

Ashden Awards winners showcase climate solutions -

‘Sufficiency’ key alongside energy efficiency & renewables, says IPCC

‘Sufficiency’ key alongside energy efficiency & renewables, says IPCC -

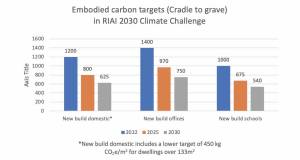

RIAI launches 2030 climate challenge

RIAI launches 2030 climate challenge -

Climate action plan sets embodied carbon targets for construction

Climate action plan sets embodied carbon targets for construction -

Grant invests in biofuel tech for oil boilers

Grant invests in biofuel tech for oil boilers -

Architects call for urgent climate action ahead of COP 26

Architects call for urgent climate action ahead of COP 26 -

The PH+ guide to overheating

The PH+ guide to overheating -

Net zero carbon plans back renewables over fabric

Net zero carbon plans back renewables over fabric -

Building sector must show bold climate leadership

Building sector must show bold climate leadership -

Deep retrofit crucial to green recovery, climate committee says

Deep retrofit crucial to green recovery, climate committee says