Geoff and Kate Tunstall

Geoff and Kate Tunstall

- New build

- Posted

5 years in a passive house — the occupants’ view

In April 2010, Geoff and Kate Tunstall moved into their pioneering house at Denby Dale. It was one of the UK’s first passive house projects, and the first to be built with a traditional British cavity wall system. Five years later, how are the Tunstalls finding life in a passive house?

When we set out to build a new house, we had a number of goals. We wanted a home to retire to, and we wanted to downsize. We wanted a house that was comfortable, healthy and easy to maintain. In terms of design, we wanted it to be full of light, contemporary and fairly minimal. And in terms of its impact on the environment, we wanted something with lots of natural materials that consumed little energy and water. We had a terraced cottage in Denby Dale, and we had a large garden. So we decided to build the house at the bottom of the garden — luckily the orientation was perfect, just slightly off due south.

We wanted something that would be very high performance, but we only had a modest budget of £150,000. At the start, we were going down the route of focusing on renewables and other technologies. Then we went into Green Building Store one Friday afternoon to look at windows and sanitaryware, and we talked with (operations and construction director) Bill Butcher. He said: you don’t want any green bling, what you need is a passive house.

As part of our research we went to visit a couple of passive houses in Austria. It was outstanding. We immediately noticed how warm it was inside, and how fresh the air was. We looked at each other and immediately said: yes, this is what we want. We brought lots of passive house books and information back with us to the UK. Remember this had never been done in Britain before, it was all a step into the unknown.

Early on we had to go into negotiations with a local builder over a ‘ransom strip’ at the bottom of our garden, which we ended up biting the bullet and paying £18,000 for. But the delay gave Bill and Chris Herring at Green Building Store time to do loads of drawings and perfect the design, so consequently the build went very smoothly. The whole project team had a meeting on site every three weeks — these were crucial to the success of the project.

We were very hands on during the build. We went for cavity wall construction because it was tried and trusted, and because Green Building Store had built the Longwood low energy house in the 1990s with a cavity wall system, so they had experience with it.

But in the early days, after we first moved in, we didn't know how to run the house properly. It was a steep learning curve and it took us a while to work it all out. During the build we couldn’t find a small enough boiler for the house. The smallest available was 4kW, when we only needed 1.1kW. As a consequence, in the first six months there was a problem with the boiler ‘cycling’ (switching itself on an off) due to the small amount of water in the central heating system (as there is just one radiator and two towel rails to heat the house). The first winter was very cold and often we just turned up the heating full blast and as a consequence the house sometimes overheated up to 26C in the upstairs rooms. At the time we didn’t understand that given the thermal mass of the house it heats up slowly, but once you realise it’s hot and turn the heat down, it takes a while to cool down again. Once you understand how the house works it’s much easier to control.

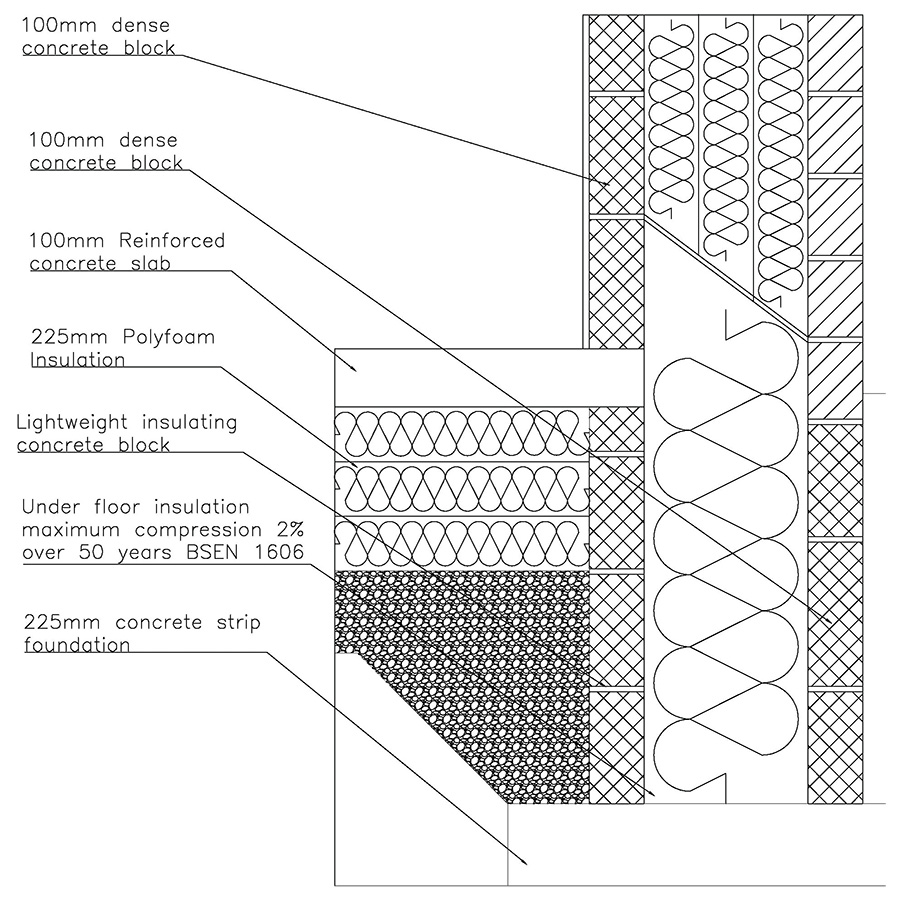

A cross sectional drawing of the foundations and ground floor

Another issue in the early days in winter, was low humidity and dryness. Geoff would wake up, when the atmosphere was drier, with a dry throat. It was only after re-reading the MVHR manual, written in translated German and not always easy to follow, that we realised lowering the fan speed helps to retain humidity. On hot summer days, we now use ‘Mediterranean purging’ (opening windows at night to cool down the building, and closing them during the day to prevent warm air coming in) to moderate temperature increases.

Because of the ‘cycling’ and lack of control over the boiler, we actually turned it on and off completely at certain times. We were able to make significant savings straight away by doing that. But then Green Building Store installed a new operating system which means the boiler is regulated much better now. This new operating system works by controlling the boiler more accurately — the only downside is that it can’t take into account the effect of passive solar gain on internal temperatures.

Still, the boiler is now much more manageable. (On one of their more recent projects, the Golcar Passive House, Green Building Store has used a thermal store in conjunction with the boiler, which means there is a much bigger volume of water and no danger of the boiler cycling).

Insulated blocks were used on the inner leaf below the floor slab to minimise any thermal bridging, with natural Yorkshire stone externally and a 300mm cavity filled with EPS insulation below DPC & 3x100mm Knauf DriTherm fibreglass insulation batts above with Ancon TeploTies to minimise thermal bridging

There was a teething issue with the MVHR (mechanical ventilation with heat recovery) system too. Andy Farr (Green Building Store’s MVHR technical manager) came to visit us early on and found there was no fresh air coming into the house at all. He asked how we’d been feeling, and whether we were tired, but we hadn’t noticed anything. He then found that a thin grille on the outside of the inlet duct was clogged up with seeds and leaves from the garden. He immediately removed the grille and the system worked fine (suffice to say Green Building Store no longer use those grilles on its MVHR systems).

Otherwise, because the house is based on a fabric-first approach and most of the technology has gone into the building itself (in term of insulation, airtightness, low cold bridging), there aren't many things that can go wrong. The house runs itself. Whatever we do to it, the house runs along performing perfectly, hour after hour, day after day, year after year. If a house is built properly, which this one is, you don’t have to do much with it, and the only tweaks we’ve made have been minor.

Continuity of insulation in the roof space, helping to cut out a thermal bridge

Much of passive house design is subtle and under the radar, it's not bling bling. We're so used to the comfort now we don't notice it, it's the norm. We don't have to think about it. We have been in the house for five years now. In winter or summer, the house is a warm and comfortable 21C inside, whether it’s minus ten or plus 24C outside.

When people come to visit the house and ask us what’s it like to live in a passive house we say: “you tell us – you’re sat in one – what does it feel like?” You have to experience a passive house for yourself to understand how it’s different. It has an ever-so-comfortable environment that is steady and unchanging throughout the house. There are no draughts or uneven temperatures.

In many ways it's spoilt us for other houses. When we go away to someone else's house or a hotel, we love to come back and walk back into this comfort again. We went away to a country cottage in Cornwall a couple of years ago. It had thick stone walls and was draughty and bitterly cold. We were feeding money into the electric fire and we were thinking: what are we doing? Moreover, not only is Denby Dale extremely comfortable, it's also a healthy house because the air is fresh and continually changing, and is filtered by the heat recovery ventilation system.

We think that the PHPP software used to design passive house buildings should stand for Passive House Performance Prediction (instead of Passive House Planning Package), because it is such an accurate predictor of building performance. PHPP modelling has been fundamental to achieving a realisable goal of a comfortable, cost-effective, affordable, healthy home.

We reckon that it costs us around £120 a year for heating. If you look at the cumulative cost over five years, that's £600 to heat the house – some people could be paying that for six months of heating bills.

Rather than permanent brise soleil, retractable blinds provide shading when necessary

Including electricity too, our total energy bill comes to about £500 a year, but we get about a £500 feed in tariff from our solar PV system, so our net energy cost is approximately zero, which is amazing. In our old house we were paying £1800 a year for all the energy bills, so we’ve made massive savings. There's also the sustainability side of it — we're using a fraction of the fossil fuels that we were in our old house.

The MVHR system is working well now and is running smoothly twenty-four seven. The only time it goes off is when we change the filters twice a year. Filters cost about £60 a year, so we have spent around £300 over the last five years to keep the MVHR system running efficiently.

We always wanted to make the Denby Dale passive house available to visitors as a resource. We’ve had at least 500 people through the house over the last few years, at passive house open days and at other times. Visitors have included shadow ministers, US passive house designers, schoolchildren, university students, building apprentices, self-builders, co-housing enthusiasts, architects, builders, and local councillors and MPs.

We hope that these visits have helped people on their passive house journey, just as we were helped when we first visited passive homes in Austria. It is really important that people get to experience the comfort, warmth and air quality of passive house buildings first hand to help spread the word.

We have noticed changes in awareness of passive housing over the last five years. At first visitors used to ask ‘what is passive house?’ But now more and more visitors already understand what it’s all about, echoing a shift in awareness in both the construction industry and among the general populace.

We are convinced that passive house will continue to grow because it’s a win-win-win situation. It wins on comfort, it wins on cost, it wins on sustainability. It wins in addressing fuel poverty, comfort and energy efficiency. And every time a passive house is built there is a mushrooming of expertise, understanding and knowledge.

Spiral ducting boosts the efficiency of the MVHR by reducing resistance

Monitoring reveals a comfortable, ultra low energy house

To better understand the performance of the Denby Dale passive house, the Centre for the Built Environment at Leeds Metropolitan University undertook a two year monitoring project on the house. Leeds Met researchers osbserved the construction, conducted air pressure tests, installed temperature, humidity and CO2 monitors inside and outside the house, set up a small weather station, and interviewed both the occupants and the team from Green Building Store.

The research found that, even though daily average temperatures outside ranged from below -5C to above 20C, inside they generally stayed between 20C and 25C. Though there were a few incidents of overheating at first, the use of external blinds and purging the building of heat at night by opening the windows has helped to prevent this, along with the use of the MVHR summer bypass feature.

Regardless of conditions outside, relative humidity inside generally stayed between 40 and 60% inside the house. The clients have learned to deal with times of low humidity by turning down the MVHR flow rates, and even just using a wet towel. The gas boiler used 5095 kWH in its first calendar year, but just 3471 kWH in its second year, as the Tunstalls got to grips with the issues of the boiler cycling (see main article). Electricity demand was roughly 2,000 kWH per year, with the solar photovoltaic system producing around half this amount. The demand for space heating is estimated to be between 9 and 20 kWh/m2/yr, according to the the research team's report.

All new housing should be built to the passive house standard, but if we are going to prioritise anything it should be social housing. It is really annoying that our government is promoting house building and a new crop of homes for first-time buyers, while at the same time talking about weakening energy efficiency standards. They're not future-proofing new houses. Energy is not going to come down in price in the foreseeable future.

Undoubtedly one of the biggest challenges is getting support for passive house from government, where it is up against various vested interests. It could be argued that big energy companies have a vested interest against passive house buildings because they don't want less energy being used. Politicians won't do anything about it unless there is a groundswell of people who want something to happen. It was good to be visited recently by Jonathan Reynolds, the shadow minister for energy and climate change, who seemed genuinely interested in passive house.

Meanwhile a local Green Party councillor Andrew Cooper, who has also visited Denby Dale, has been working on a policy to introduce passive house as a requirement on any land sold by our local authority Kirklees Council. Politicians need to pick up the baton and run with it. If we embrace passive house, society wins, the people who live in it win, the housing stock wins and the planet wins.

More information on the Denby Dale passive house, including technical films and a 40 page technical briefing, is at www.denbydalepassivhaus.co.uk

Selected project details

Clients: Geoff & Kate Tunstall

Architect: Derrie O’Sullivan Architects

Passive house design, main contractor, QS & MVHR: Green Building Store

Structural engineer: SGM Structural Design

Electrical contractor: John Gregson

Insulation supplier: Knauf Insulation

Solar thermal & solar PV: Eco Heat and Power

Airtightness products: Ecological Building Systems, via Green Building Store

Passive house certifier: Warm

External blinds: Dearnleys

Clay plaster: Womersley’s

Thermal blocks: Celcon

Basalt wall ties: Ancon

Condensing boiler: Vaillant

Additional info

Building type: 118 square metre detached two-storey masonry cavity-wall house

Location: Denby Dale, West Yorkshire

Completion date: April 2010

Budget: £141,000 (basic build costs)

Passive house certification: certified

Space heating demand (PHPP): 15 kWh/m2/year

Heat load (PHPP): 10 W/m2

Primary energy demand (PHPP):87 kWh/m2/year

Airtightness (at 50 Pascals): 0.33 ACH

Energy performance certificate (EPC): N/A

Measured energy consumption: 9 to 20.7

kWh/m2/yr (May 2011 to May 2012, estimate based on monitoring data)

Ground floor: 225mm Knauf Polyfoam insulation under 100mm reinforced concrete slab. Lightweight 100mm Celcon 7KN low thermal conductivity blockwork used for inner wall leaf below the slab to minimise thermal bridging through the 225m strip foundation. U-value: 0.104 W/m2K

Walls: Masonry cavity walls (natural Yorkshire stone externally and dense concrete block internally) forming a 300mm cavity fully insulated with Knauf DriTherm Cavity Slab 32 mineral wool above the ground floor slab and polystyrene below. Walls finished internally with two coats of wet plaster for airtightness. Lightweight concrete blocks used for inner leaf below ground floor level to minimise thermal bridging from strip foundation (see 'ground floor'). Teplo Tie basalt resin cavity wall ties. U-value: 0.113W/m2K

Roof: Slates externally followed underneath by bobtail roof trusses wit 500mm fibreglass insulation, which meets the cavity wall insulation to prevent cold bridging. 18mm OSB board underneath for airtightness, sealed with pro clima tapes, with service cavity void underneath. U-value: 0.096 W/m2K

Windows: Ecopassiv timber triple-glazed windows with argon fill, low-e coatings and polyurethane-insulated thermal break in frame. Average overall U-value: 0.8 W/m2K

Heating system: Vaillant Eco Tec 612 (4.8 kW) gas boiler supplying one radiator in the living room and two towel rails. Duct heater installed in the supply side duct of the MVHR system. 2 x Schueco Premium Line solar thermal panels for domestic hot water. Primo twin coil ITSI 300 litre cylinder.

Ventilation: Paul Thermos 200 MVHR heat recovery ventilation system — Passive House Institute certified to have heat recovery rate of 92%.

Electricity: 1.2 kWp BP Solar photovoltaic system with Sunny Boy SB1100 inverter Green materials: Bamboo flooring, natural paints

Image gallery

Passive House Plus digital subscribers can view an exclusive image gallery for this article. Click here to view