- Feature

- Posted

Doctor's orders - The complex relationship between energy retrofits and human health

There is no shortage of anecdotal evidence that home energy retrofits, done well, can improve the health of those who receive them — and equally there are horror stories about shoddy upgrades causing damp, mould and illness. But what does the evidence say about how energy upgrades effect occupant health, and what lessons can be learned for the future of how we renovate our homes? Kate de Selincourt reports.

This article was originally published in issue 32 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

In July, the House of Commons Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee released a report which was highly critical of the current lack of progress in building energy efficiency work, particularly in England. The report urged a seven-fold increase in the installation rate.

“A major upgrade of the energy performance of the UK’s entire building stock will be a fundamental pillar of any credible strategy to reach net zero emissions, to address fuel poverty and cut energy bills,” the committee told the government.”

This report followed close on the heels of the Committee on Climate Change’s recommendations for new and existing homes which, unsurprisingly, also urged the government to increase the uptake of energy efficiency measures.

Whether or not the UK government chooses to act on this advice is anyone’s guess. However, if it does, there are expected to be numerous benefits besides emissions reduction. One of the obvious benefits would be improved public health.

A calculation by BRE that poor housing in the UK costs the NHS £2.5bn per year is often cited. The assumption is that fixing the housing will avert this expenditure – a reasonable assumption, given the strong association between poor health, and excess winter deaths, with poor quality housing. However, this is only an assumption.

Anecdotally, there is evidence that home energy improvements can indeed improve health. For example, when social landlord Gentoo began to replace boilers and insulate tenants’ homes, they were struck by how often customers said their health improved.

“Families reported being happier and their wellbeing had increased. Not just in one or two homes, but in home after home, street after street. We were being inundated with huge amounts of anecdotal evidence to suggest the biggest difference we had made since retrofitting the home was to the health of our customers.”

Gentoo attempted to put numbers on these effects. They studied the impact of their energy efficiency installations more systematically – and found that across 200 hundred households where boilers and windows had been upgraded, tenants on average said they felt healthier and used the NHS less (equivalent to around a 15% reduction in spending per household compared to before the improvements).

Elderly occupants of homes with upgraded ventilation, CO monitors & fire alarms were admitted to hospital 39% less often – with a 57% drop in emergency admissions for respiratory illness.

This is far from the only study to recorded positive health outcomes from home energy interventions. Researchers asked tenants of Nottingham City Homes about their health and satisfaction before and after the external wall insulation was fitted. They too said their health had improved, with statistically significant improvements in mental well-being, including reduced anxiety, and reduced use of NHS services.

Meanwhile, charity National Energy Action (NEA) co-ordinated a range of heating and insulation measures for several thousand fuel poor households living in inefficient dwellings, and over 700 were asked about their experiences before and after the measures were installed. Over a third said their physical health had improved, with just a few (6%) saying their health had worsened, and the rest reporting no change – in other words, a trend towards better health after energy retrofit.

There are many studies like these, and a fair number of them do report health improvement, though not all. But there have been criticisms of the research methodologies: not all have a control group for comparison, so unconnected factors, such as one winter being milder or harsher than the next, cannot always be ruled out as the cause of any changes in health.

Also, unlike with placebo-controlled trials in medical research, people always know if they have had their boiler replaced or their walls insulated, so their expectations may be affecting their health, or their perception of it — especially if they are being specifically asked about it.

There are also studies that have shown little or no measurable impact. And even though researchers generally advance a plausible explanation for why this might be — numbers too small, follow-up period too short, etc — the suspicion has to remain that some improvements simply do not make much difference to occupants’ health.

Retrofitting for air quality

Replacing open fireplaces, stoves or ranges burning solid fuel with a central heating system that brings comfort at the flick of the switch has been demonstrated in some of these studies (for example, the work from Northern Ireland) to bring benefits to householder health.

None of the studies referred to in the main article recorded indoor pollutants other than moisture, and they did not measure indoor air quality in the study homes. But it is interesting to consider whether eliminating a source of smoke and pollution form people’s homes may have played a part in improving their health.

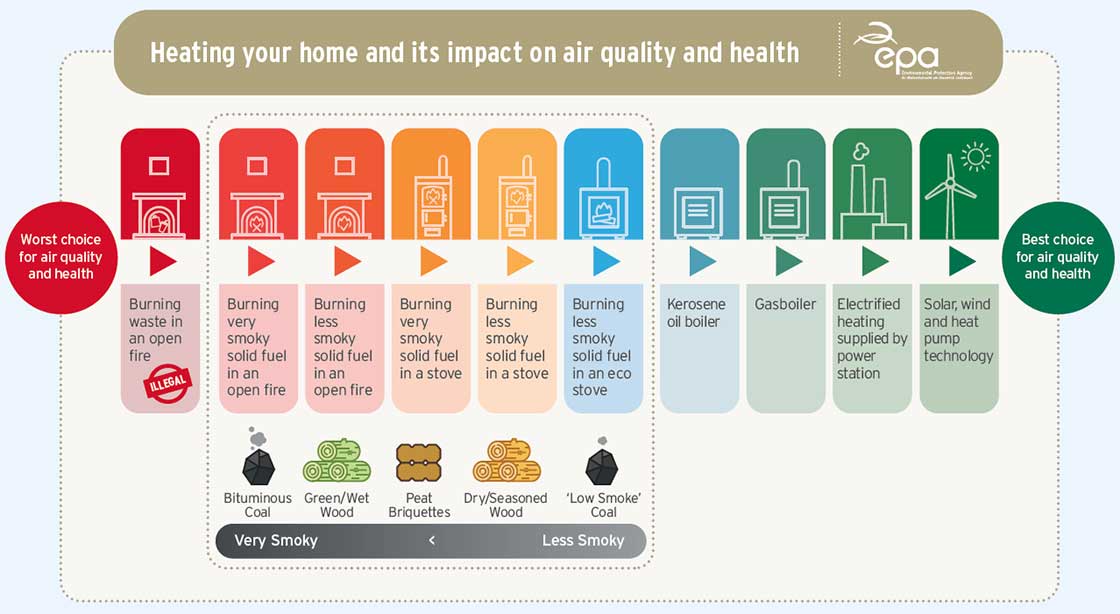

Solid fuel burning is a source of many toxic and irritant pollutants, and Ireland’s Environmental Protection Agency has recently published monitoring data showing that levels of carcinogenic polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PACs) derived from solid fuel combustion (coal, wood and turf/peat) exceeded EU reference levels at several test locations last year. Solid fuel combustion, notably in wood stoves, is also a significant (and growing) contributor to particulate pollution in the UK, accounting for as much as 30% of locally produced particulates in some cities.

Domestic solid fuel burning introduces harmful air pollution into dwellings both directly, and also when ventilation air from outside is contaminated with chimney smoke – which it generally will be, to a greater or lesser extent.

It is therefore plausible that some of the health benefits enjoyed by the recipients of new central heating systems came via reductions in pollutants such as particulate matter, NO2 and SO2. While there is no evidence on this either way, it is also worth noting replacing solid fuel heating with something cleaner benefits not only the recipient, but the whole neighbourhood.

Biggest study to date

Probably the most convincing positive results to date are a set of studies that looked at different aspects of the health of a group of 30,000 tenants of a single social landlord and studied some for up to ten years.

This group of studies is valuable because it involved so many people, which increases the statistical power of the findings, and the follow-up period was far longer than is usually possible in research of this kind, again making it likelier that any health effects seen were not just a temporary boost based on expectations.

Perhaps most powerful was the fact that, uniquely for a recent study in the UK, the researchers had direct access to people’s (anonymised) medical records, so were able to compare the health service use of all 30,000 occupants (it would have been impossible to interview so many people).

The landlord, Carmarthenshire County Council in Wales, carried out a wholesale home improvements programme to bring all its homes up to the Welsh National Housing Standard. The measures installed varied dwelling-by-dwelling, based on what each needed. Improvements included insulation, heating upgrades, new doors and windows, and because falls at home are a major cause of injury and hospitalisation, improvements to paths and steps.

The researchers were therefore able to look directly at impacts on NHS spending. It was also possible to compare different subsets of tenants according to which changes had been made to their homes.

The main part of the study looked at emergency admissions to hospital for respiratory and cardiovascular problems, plus falls and burns — for all residents, but with a focus on those over 60. Residents over 60 living in homes where improvements were made went to hospital significantly less compared with those living in homes that were not upgraded.

Admissions to hospital fell by between one quarter and one third across the improved homes, depending on the measures that had been installed. Strikingly, the biggest improvement of all was seen in homes where the electrical system had been upgraded – an upgrade that included carbon monoxide monitors and fire alarms, but also ventilation.

In these homes, occupants over 60 were admitted to hospital 39% less often after the measures were installed, and there was a 57% drop in emergency admissions for respiratory illness in particular.

Indoor air quality

Anyone working with people in fuel poverty knows that cold homes are often damp as well, yet moisture and indoor air quality have not been a prominent concern in the mainstream UK energy efficiency programmes to date. Damp is known to harm health, independently of cold. In some analyses, damp seems to be more closely related to harm than cold does.

So, it is perhaps unsurprising to learn that ventilation, alongside energy efficiency measures, has a benefi cial impact on health. This has been seen in other studies – smaller ones, often targeted specifi cally at people with respiratory conditions (often children).

In these cases, the installation of ventilation, sometimes alongside heating, has been associated with reductions in symptoms and in fewer days missed from school.

Warming a house can help with dampness to an extent, especially with dampness exacerbated by cold (it won’t repair a leaking gutter). When a home is warmer, people are more likely to ventilate, and surfaces may be warmer and attract less condensation.

In studies where very old, cold homes have central heating installed, damp has often been reported to reduce. In one study in rural Northern Ireland, three quarters of unimproved homes reported condensation, damp or mould — but in half of these the problems were alleviated after the installation of new heating systems.

Other intervention studies have also found that homes became drier after new heating or other energy retrofit measures were installed. But this is not always the case.

For example, in a survey of people who had had their homes improved under the NEA charity’s health and innovation programme, participants consistently reported that their homes were warmer or at worst, the same as before. But the responses relating to damp and condensation were more equivocal. Although more people agreed there was less damp and condensation after the retrofit, the difference was not overwhelming, and quite a few disagreed with the proposition — suggesting that while energy efficiency measures may tend on balance to reduce dampness, they are not always enough on their own.

Many retrofit measures reduce air leakage – sometimes this is the main objective – so if existing ventilation is already inadequate, as it so often is in British housing, new problems may arise.

A small study of indoor conditions after retrofit by researchers at Cardiff University illustrates this. When new mechanical ventilation was installed, internal humidity did not rise even when homes received measures that may be likely to reduce air infiltration, such as external wall insulation. However, in a subset of the dwellings where ventilation was not installed, but other measures such as new windows were, there was a small rise (around 5%) in relative humidity.

This is concerning, especially when seen alongside results from another group of occupants, a subset of the tenants in the Carmarthenshire study mentioned above. This subset comprised around 2,000 people who were interviewed directly about their health. This group was divided according to measures received and included a group whose homes had received external solid wall insulation plus ventilation, and others whose homes had received cavity wall insulation but no ventilation.

Those who received external wall insulation, which was always accompanied by extractor fans, reported improved health — in fact external wall insulation plus ventilation was associated with the largest improvements of all the measures analysed in this subset, in terms of both respiratory and general health.

However, researchers found a worsening of reported health outcomes for occupants in homes which had been fitted with cavity insulation – which again, was not automatically accompanied by ventilation.

As the authors wrote: “The installation of the majority of individual housing measures (new windows and doors; boilers; kitchens; bathrooms; electrics; loft insulation; and insulation) were associated with improvements in several social and health outcomes... There were however a few exceptions. Most notably...in contrast to the expectations, the installation of cavity wall insulation was associated with poorer [i.e. worsened] mental and general health, and an increase in reported respiratory symptoms.”

It is not known how the internal environment changed in these dwellings, though it might be reasonable to assume that, by analogy with the study described above, indoor humidity may have risen – and with it, possibly an increase in mould or dust mites. Other research in Wales also suggests issues with cavity wall insulation. BRE Wales investigated instances of both cavity and solid wall installations where problems had arisen. Issues reported included damp and mould inside dwellings and sometimes damage to the building fabric.

The BRE analysed the probable causes of the issues. They found that in many of the problematic cases, no assessment of the ventilation system had been made prior to the installation, that in some cases narrow cavities had been insulated, some houses were in high exposure areas. In some cases, cavity insulation had been installed in homes where the wall was in poor condition. This can allow the insulation to become waterlogged and cause damp issues inside.

Thus, there are two potential issues here – insulation installed in walls that are wet or at risk of becoming so, and lack of ventilation. Both increase the risk of damp and mould as well as other forms of indoor air pollution. Both however, come back to quality control in retrofit.

Who is most vulnerable to cold?

It is well-established that the risk of cardiovascular disease, and respiratory diseases such as asthma, are more common for people living in housing that is hard to heat. Illness and death rates from these conditions increase in winter – and increase most for people in the worst housing and in the worst poverty (all too often the same people).

Less well-recognised is the fact that dementia sufferers are equally vulnerable to cold – in fact excess winter deaths from dementia in some years outnumber excess winter deaths from heart disease. While dementia may or may not be made more likely by cold housing (there has been remarkably little research on this) dementia sufferers in cold homes are particularly vulnerable to just getting too cold, with the harm that then ensures.

Dementia sufferers may be both less likely to notice they are cold, and less able to work out what to do about it. Sufferers often forget to eat, too. Falls in cold conditions, when the person is alone and lies undiscovered for many hours on a cold floor, are particularly dangerous and can lead to a severe deterioration in health, or even death.

Living in a home that you can’t afford to heat also makes a whole range of other health problems likelier in the first place, and it makes many existing conditions worse.

Living with a physical health problem or disability can also make it harder to cope with the cold: if you have mobility problems or a reduced appetite you are likely to feel the cold a lot more (but ironically, are quite likely to be stuck in that cold house more of the time). And if your home is cold and your income is low, the practicalities of dealing with illness and disability – for example, doing more laundry – will become harder too.

Problems that have been highlighted as making cold especially tough include spinal injury, arthritis and rheumatism, sickle cell disease, skin problems, cancer treatment and recovery – but it is hard to imagine any condition that is going to be improved by living in fuel poverty.

And yet, cruelly, having a long-term illness or disability makes you a lot likelier to be in fuel poverty – not least because your income is very likely to be constrained. Fuel poverty rates for disabled people in the private rented sector are particularly high: 35% of UK households with a disabled occupant are in fuel poverty.

There is also a particularly close link between poor housing and poor mental health. Data from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007, a survey of 7,400 people in England, showed that being unable to heat your home in winter, having a combination of fuel debt and other debt, having mould, and restricting energy use were all predictors of mental disorders such as depression or anxiety. Research by the World Health Organization found that extensive dampness and mould at home increased the chance of depression by 60%.

Designed ventilation

Proper ventilation is needed in any dwelling. It is required in order to remove the moisture created by day to day life — and to remove numerous other pollutants from indoor air.

The Royal College of Physicians warned in 2016 that indoor air pollutants cause, at a minimum, thousands of deaths per year, and are associated with healthcare costs in the order of ‘tens of millions of pounds’.

The ventilation in homes in the UK is seldom as good as it could be, and substandard ventilation compromises occupant health. If retrofit of a house with inadequate or no ventilation reduces infiltration through the fabric – i.e. draughts – occupants will probably be warmer but alas, their air quality will be even worse, unless the ventilation is sorted out.

Ventilation should be part of every preliminary assessment of a home being considered for retrofit and remedying inadequate ventilation an absolute precondition for almost any additional intervention.

With retrofit, as with new build, the default ventilation option is still all too often intermittent extract fans in wet areas only. While the studies quoted show that this approach is better than nothing, there is too much evidence that it does not work adequately for it to be recommended, even in a relatively leaky building. Installing ‘system one’ ventilation like this is also a massive missed opportunity – both to benefit occupant health, and to cut fuel bills and reduce emissions.

System one ventilation does not leave any dwelling ‘2050 (or even 2030) ready’. The climate emergency means we need to insulate pretty much every dwelling and make them all a great deal more airtight, in order to meet our carbon goals. With an effective ventilation system installed from the start, it will be safe to improve the performance of the building fabric at any time.

Installation of continuous, centralised mechanical ventilation is the only way to prepare a dwelling for zero-carbon-compatible retrofit. This is implicitly recognised in the new PAS 2035 (see ‘The UK’s new retrofit standard’ boxout), which requires that a continuous ventilation system with demand control is installed if an energy retrofit reduces the air leakiness of the dwelling below 5 air changes per hour (at 50 Pascals of pressure) — or if it can’t be proved that it won’t do this.

A correctly designed and installed centralised mechanical extract (cMEV) or mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) system will provide effective ventilation however airtight the dwelling – it does not rely on random leakage through the building to make up the air fl ow (which in practice, doesn’t always work anyway). Instead, the ventilation system supplies all the air needed.

The UK's new retrofit standard

With the support of the government, the British Standards Institute has recently issued a new PAS (publicly accessible standard), PAS 2035, for domestic retrofit. This includes requirements on providing adequate ventilation when houses are being retrofitted for energy efficiency.

The new standard was developed in response to instances of retrofit failure, where installations were faulty and in some cases buildings were damaged, and householders failed to get proper redress. The new scheme sets out the qualifi cations and responsibilities of individuals involved in designing and delivering energy retrofit, and formal processes for managing risk.

The standard is expected to become a requirement in all UK government-mandated energy retrofit programmes (such as ECO) within a few years and may also be adopted as a requirement by other funding bodies such as banks.

Retrofit must meet the PAS standard if it is to be covered by the newly introduced “Quality Mark” guarantee, which offers consumer redress; the Quality Mark is also a government-backed scheme.

Problems beyond ventilation

Failing to check and remedy ventilation is an established failing of the retrofit industry, but it isn’t the only one. Ventilation cannot remedy the issues caused by faulty wall insulation that lead to water penetration, and in turn to damp, mould and harm to occupant health. External wall insulation (EWI) has also been subject to water failures (see article on Preston insulation failures, in Passive House Plus issue 24) but cavity wall insulation (CWI) deserves at least as much attention in this regard.

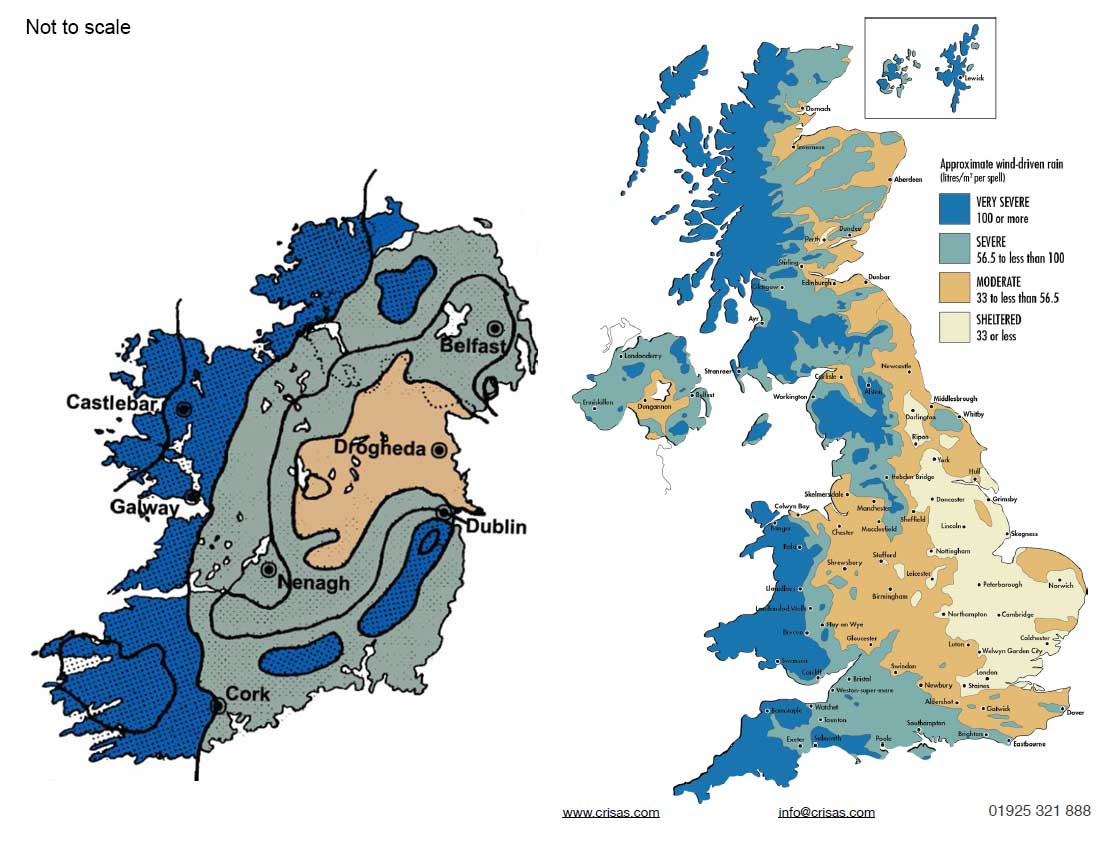

Many areas in Wales, the west of England and Scotland, and much of Ireland in particular have climates that may not be suitable for retrofitting CWI (see map).

Maps showing geographical exposure to wind-driven rain for Ireland & the UK. Some experts believe that areas with high levels of wind-driven rain may be unsuitable for cavity wall insulation. (Irish map: Joseph Little, adapted from BS 5262 coloured as per BR 262 UK map: BR 262)

Additionally, CWI should never be added where the outer leaf of a wall appears to be in bad condition (with cracked pointing or render, for example).

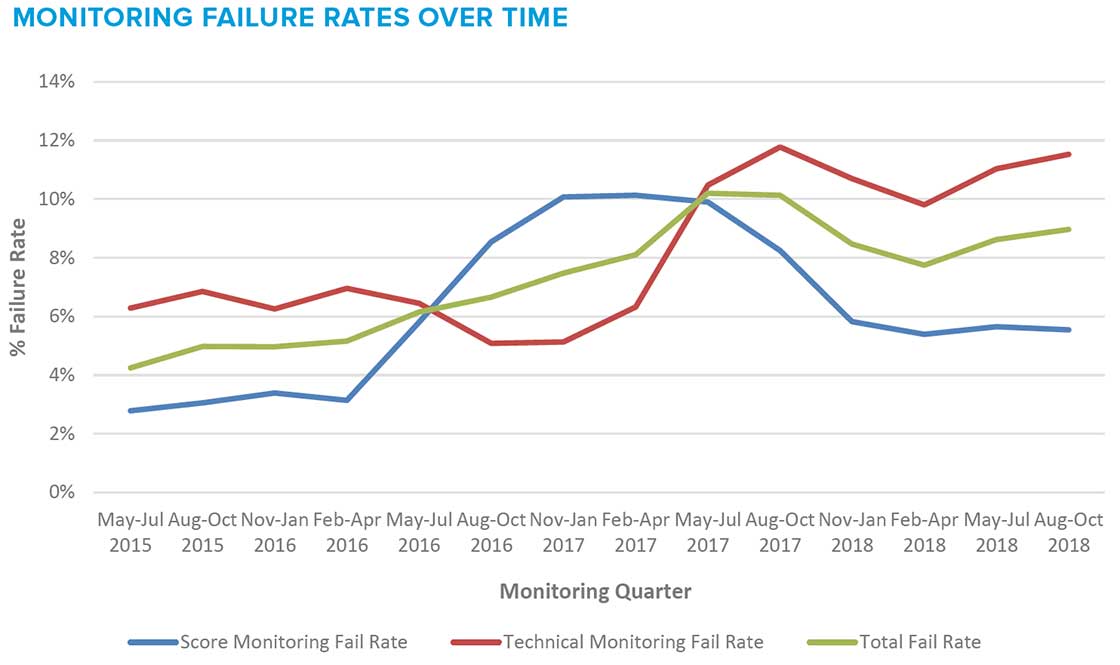

Ofgem monitoring of homes retrofitted under ECO (energy company obligation — the scheme requiring energy providers to upgrade homes) has repeatedly shown that CWI, along with other retrofit measures such as EWI, is installed inappropriately in a significant percentage of cases – for CWI this has been between 5 and 10% of sampled installations in recent years. In fact, overall technical failure rates rose over the duration of the second phase of ECO (see graph showing failure rates for all measures combined).

Monitoring failure rates for ECO-funded retrofits in the UK between 2015 and 2018

Yet Ofgem only refused energy company claims for carbon savings under ECO when an installer’s technical fail rate was over 10%. Ofgem commented that: “The average failure rates for CWI measures (5%) and non-high rise EWI measures (11%) were notably high”.

Furthermore, 19% of the installations (of all kinds, including cavity wall), which were supposed to have a guarantee, proved on investigation not to have a valid guarantee in place.

Clearly, insufficient action has been taken so far to address installation quality. The new BSI quality standard for retrofit, PAS 2035 (see below) is a fresh attempt to address this issue, though it is not expected to impact more than a handful of retrofits for a couple of years at least.

The health and retrofit agenda

Occupant health may finally be making its way onto the retrofit agenda. In its advice to the government on upgrading the energy performance of dwellings, the Committee on Climate Change, crucially, insists that the health of occupants must not be compromised by energy retrofit – but rather, should be enhanced. “Upgrades or repairs to homes should include increasing the uptake of: passive cooling measures (shading and ventilation); measures to reduce indoor moisture [and] improved air quality,” it says.

“An integrated approach to design, build and retrofit is needed. Regulations around ventilation must evolve to keep pace with improvements in the energy efficiency of buildings, and there is a need for a more coordinated approach to the requirements for energy and ventilation in buildings. Rather than piecemeal incremental change, long-term investments that treat homes as a system are needed.”

The evidence shows that this position is right, and when carried out appropriately without neglecting ventilation, retrofit can indeed improve occupant health.

Done well, an energy retrofit can be transformative. As one grateful recipient explained: “The new heating was installed when my brother had bowel cancer. It got to a point where even the slightest chill would be a detriment to him. It gave us more control and was more efficient. It helped keep him from shivering when trying to keep warm, it helped him recover. It couldn’t have come at a better time in his life.”

There is no reason why anyone who could benefi t from a warmer, healthier home should be suff ering in cold, damp unhealthy accommodation. We know how to make it better.