- Water

- Posted

Waste water woes

In light of Ireland’s poor performance in the recent European Environment Agency Report on drinking water quality, the issue of Ireland’s wastewater treatment from one off houses is poised to stay in the spotlight. Construct Ireland’s Pat Kennedy, environmental engineer, investigates.

Ireland is in the midst of a controversial media debate on the issue of wastewater effluent treatment from “one off” housing. Ireland produces 50 million gallons of effluent from 1.2 million people each day. This correlates to about 350,000 - 400,000 individual wastewater systems from one off houses in the country with the addition of approximately 18,000 of such systems each year as more houses are built. According to Frank Clinton of the EPA, ‘there is a significant concern in relation to contamination of ground water as a result of poorly designed and maintained septic tank systems’.

Typical Effluent characteristics:

Total solids 200 mg/litre

Total Phosphorus 10 mg/litre

Total Nitrogen 50 mg/litre

COD 400 mg/litre

BOD 300 mg/litre

Total Coliforms 107 - 109

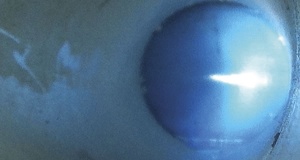

This effluent poses a threat to human health when it enters our drinking water supply. Microbial pathogen in forms such as bacteria, viruses, E-Coli and Cryptospiridium in the effluent cause a variety of very serious health problems to the user. The environment is also put at risk through inadequate systems. Contamination of watercourses, mainly in the form of nitrogen and phosphorus, facilitates the mass growth of algae and plant life. In a process called eutrophication, oxygen is stripped from the water (represented in the BOD and COD parameters) by the abundant plant life, resulting in a suffocation of animal life like fish, which rely on this oxygen to breathe.

Microbial contamination of groundwater in Ireland is very high, especially in comparison to some of our European Union counterparts. In many areas of Ireland between 30 and 50 % of private, domestic and farm wells are polluted. The most recent EPA survey of groundwater quality, from 1998-2000, recorded positive faecal coliform counts in 38 % of samples taken from 134 monitoring stations, whilst 20 % of samples had faecal coliform counts greater than 10 per 100 ml, indicating gross contamination (EPA 2002). It’s likely that there are areas in Ireland where more than 70 % of private wells contain faecal bacteria at some time during their use. The two main potential sources of this are organic waste from farming and effluent from on-site wastewater systems. This scale of this problem is compounded, because for many houses, especially in rural areas, private water wells are located very close to the site of the wastewater treatment system, which greatly increases the risk of contamination from an inadequate system.

There are no definitive statistics on the impact of on-site systems on surface water. However it is known that a large number of on-site systems are piped to watercourses, in addition to water seeping from the soil to the underlying water table, which eventually enters our surface watercourses. In the Three Rivers project report by MCOS in 2002, unsewered population were estimated to contribute 7%, 8%, and 3 % of the total phosphorus in the Suir, the Boyne and the Liffey catchments respectively. Septic tanks contributed 12 % of the estimated sectoral MRP

(molybolate reactive phosphorus) contributions in the Lough Leane catchment in 1999 (Kirk, McClure, Morton & Petit 2000).

Once effluent leaves a septic tank system it is generally directed into a percolation bed or ‘soak pit’. It is here that the final cleansing of the effluent takes place by the soil microbes.

There must be adequate soakage and attenuation, which means that the percolation bed must be porous enough to allow effluent to freely flow into and around the soil, but not so free flowing that effluent washes straight through the soil, without being treated. For proper disposal of effluent with minimal environmental and health risks, a minimum of 0.6 to 2 metres of suitable free-draining soil and subsoil is required, depending on the type of system and the hydrogeology. Assessment of site suitability depends on a wide variety of factors, such as soil depth and type, bedrock type, water table levels, and proximity to wells and watercourses. The projected quantity of effluent to be treated, and projected effluent attributes such as COD, BOD and total solids, must also be considered. This in turn depends on parameters such as the number and age of house occupants and the individual home’s wastewater disposal system.

The assessment process is made even more difficult in light of Ireland’s recent boom in unsewered suburban housing developments around most of the country’s large towns and cities, given that “the most important factor influencing groundwater contamination by septic tanks is the density of systems in an area” (Yates1985). A plot of land around the percolation bed will have a finite limit as to how much effluent it can effectively treat. Therefore, the greater the number of percolation beds in a region, the greater the like hood of contamination.

Coupled with the complicated and variable nature of Ireland’s geology and hydrogeology, evaluation of site suitability for onsite systems is a very difficult process, requiring specific expertise in range of disciplines. This highlights the need for everyone from homeowners to architects to seek out properly trained professionals to undertake these site assessments.

A positive initiative has been taken by the EPA, in conjunction with FAS and the GSI, in providing a course to specifically qualify people in this complex area. This course creates a standard for site assessment across the country, thus potentially eliminating poor site assessment and future pollution problems.

There is a growing belief that the EPA’s Manual (2000), which is currently being reviewed and updated, and Groundwater Protection Response (2001), should become the guidance documents for the location of on-site systems, and in particular for site assessments. These publications set out a robust framework for locating on-site systems in a way that minimises impact on the environment and human health. They significantly upgrade the building regulation SR6 (NSAI 1991) and take greater account of both the need for a comprehensive site characterisation as a basis for decision-making, and advances in design and engineering of treatment systems.

As Sean O’Connor, environmental engineer highlights, “the upgraded EPA documents mean that potential sites for single house developments will be scrutinised much more extensively and intensively than hertofore. This will apply where certain other developments are proposed in unsewered areas.

Significant points to note include:

*A minimum of 1.2 metres of unsaturated soils must exist, firstly between the proposed invert of the percolation system and the top Water table level, and secondly between the inner and the indigenous bedrock.

“All local aquifers (or wells) must be categorised by their type and vulnerability rating, along with the relevant protection response, as per EPA and GSI recommendations.

“Local bedrock and overburden must be identified and nominated accurately.

“Zoning per county Development Plan should include the establishment of architectural, historical and natural conservation.

“Percolation holes should be pre-soaked twice on the day before testing, with the main tests carried out and repeated twice on the next day, totalling three testings.

“All soil horizons, textures types, densities, layering PFPs and so on must be stated

The overall responsibility for attaining accurate site assessment is further established by virtue of the fact that the assessor is then obliged to recommend which effluent treatment system is potentially suited to the particular site, and/or state if and what remedial site work is necessary.

Clearly, there is a much increased onus of responsibility on the assessor than before, and this is evident in at least a threefold increase in the time-span required to carry out and report, compared to the old SR6-’91 method. Suitable and sufficient Professional Indemnity insurance is now becoming a ‘must’ and several of the Local Authorities currently insist on evidence of this from site assessors.

Once the proposed site is properly assessed it is imperative that the correct waste water system that fulfils the criteria of the site assessment is employed. Many experts stress that there is still a place for conventional septic tanks in certain regions of the country, but they are diminishing with the increase in housing density.

Wastewater treatment systems

With the advent of various wastewater technologies it is now possible to build a house on a site that would be unacceptable for a ‘normal’ septic tank. These advanced wastewater systems significantly and adequately reduce harmful effects to the environment and health, compared to conventional septic tanks.

These systems are the only type permissible in high-risk areas, where vulnerability of groundwater sources (often group water supplies) is deemed to be extreme. These systems are also necessary in a variety of other sites.

Depending on the site, and on individual preferences, higher wastewater degradation can be achieved using peat, plants or mechanically aerated wastewater treatment tanks. The aerated treatment systems provide naturally occurring aerobic bacteria within the effluent, and oxygen to significantly increase the capacity to remove organic matter from the effluent.

In addition, growth media may often be used in the form of small plastic pellets, which serve to increase the surface area from which the bacteria can reside, thus increasing the bacterial count, and therefore the efficiency of the system.

All of the tank systems available on the market in Ireland differ in a variety of ways, in size, effluent degradation capacity, electrical consumption. Each available system should be thoroughly analysed before purchase to ensure the correct system is purchased for your particular site.

When a system is being decided upon, a certain degree of product information is needed. Although Irish Agrement board certification should be a prerequisite, other product information is a must, and questions to raise include the following:

- Is the system effectively and reliably able to deal with wastewater from the house, as prescribed by the site assessment?

- What are the running costs per year?

- How often will the system need to be de-sludged? This may be a considerable expense over the life of the system.

- Do the suppliers install the system?

- Is there a maintenance contract available?

- How rigid and robust is the product, and is it possible to get spare parts and servicing for the system?

- Is there product liability, guarantee, or warranty given?

All of thee questions should be answerable in writing, thus ensuring the product’s credentials. The purchase of a wastewater treatment system of whichever variety is an extremely important long-term investment of up to 50+ years, and this should always be in mind when purchasing.

Wastewater treatment systems are not a once off product purchase but rather a lifetime investment for the protection of you and your neighbour’s environment and health. All systems without exception need maintenance to some extent. This again needs to be preformed by professionals to check the system is working and to insure the tank is desludged as often as is necessary.

There is no doubt that there is a grave danger to our nation’s water supply and environment if the issue of wastewater treatment for all ‘one off’ dwellings is not dealt with properly. Due to the various complexities and inherent danger, each stage of a system’s installation and maintenance must be carried out by qualified personnel who are willing to stand by their work, or product.

The onus of protecting our environment and health falls into the hands of everyone involved - including site assessors, product manufacturers, system installers, maintenance contractors, architects and homeowners. However the situation is more problematic, as when one home pollutes (either consciously or unconsciously), everyone in the vicinity pays the possibly detrimental consequences. As treatment system are generally located underground, and behind the house, the ‘out of site out of mind’ factor comes in to play. A house may not necessarily experience any problem in disposing of its water, like flushing the toilet, but if the system is not running properly there could be massive environmental problems afoot in the back garden.

The Department of Environment places the responsibility of water pollution from single houses on each of the individual local authorities. Enforcement of the aforementioned procedures has traditionally been weak in this country, as county councils have lacked the resources and personnel to police them.

The Environmental Protection Agency sets the standard and guides each County Council to the best practice it should employ. The situation in this country is definitely improving, and some local authorities, such as Louth County Council, have taken a proactive approach. Louth insists that by 2004 all site assessments will be carried out by personnel who have been certified through the EPA.

Many people, like Kevin McCabe, believe that the local authority should issue a form of licensing within the industry. This would ensure that the correct systems are chosen and installed properly, making the relevant people and products accountable. Percolation beds are an extremely important feature to the overall system but once they are constructed, it is difficult to prove how well they were constructed. Using photos of the percolation bed as it is being constructed, and receipts guaranteeing that the proper fill (including clay and sand) is used, would help to prove adequate percolation construction.

Proof of maintenance work carried out should be submitted to the Local Authority regularly to prove the site is complying with environmental law. This can and will reduce the incidence of pollution in Ireland in the future, and will make people accountable, ensuring that only the polluter pays, and not their neighbours