- Passive Housing

- Posted

Passive attack

Lenny Antonelli visits a new residential development in rural Carlow that boasts only the second and third certified passive houses in Ireland, and encouragingly, finds that meeting and exceeding the coveted passive standard wasn’t as difficult as expected.

A fairly typical housing development in the Irish countryside features two rather atypical dwellings. Set against the increasingly rare sight of block-built houses under construction in Killerig, County Carlow, are two prefabricated timber-framed passive houses – only the second and third certified passive houses in the country. Eight more are planned for the site, making it the first residential passive multi-unit development in Ireland.

Developed by Botanic Homes, and the vision of its founder Fergus Joyce, the passive houses at the Village development are hard to spot at first next to their more conventional cousins. Despite being built to extraordinary energy performance standards, these houses have been designed to look rather ordinary – only the absence of chimneys gives away their secret.

At 171 square metres, the houses - on the market for e465,000 each - are roomy, with large connecting living room and kitchen downstairs, along with a toilet and utility room. Upstairs are four double bedrooms, including one en suite, and a bathroom. Just ten kilometres west of Carlow town, a new road will soon put the development within forty minutes’ drive of the Red Cow roundabout. But while Killerig may be within commuting distance of the capital, this certainly doesn’t feel like the commuter belt. The setting is decidedly rural, with the Blackstairs hills providing a distant backdrop. And while commuting by car is certainly not the best way of keeping one’s carbon footprint down, it’s not the location that makes these houses worthy of attention - it’s the ultra low energy standard to which they’ve been built.

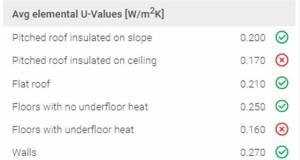

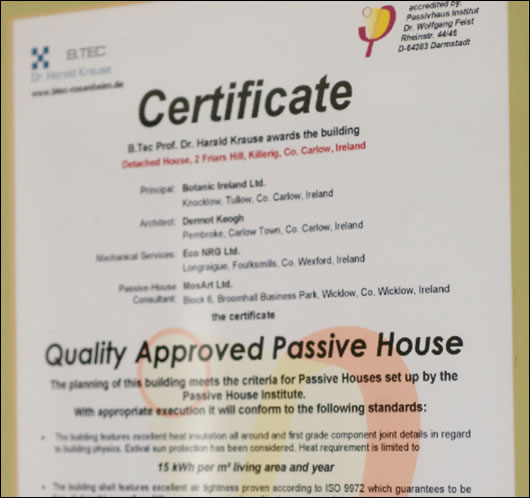

Like all passive houses, these buildings need no traditional system for heating or cooling. The houses met the German Passivhaus Institut standards for heating demand and air tightness, including a space heating requirement of 15 kWh/m2/yr, a blower door test result of no more than 0.6 air changes per hour at 50 pascals, and an entire specific primary energy demand - including all domestic electricity use - of 120 kWh/m2/year.

So what was the motivation to go passive with a typical residential development? Fergus Joyce explains: “When I bought the sites here, the plans had already been drawn up by a local architect. We realised that we wouldn’t be able to get an A rating because of the orientation and the amount of glazing facing north east. So we decided to do passive houses.”

The houses were given a B2 rating – quite surprising considering their superb energy performance, but the Dwelling Energy Assessment Procedure (DEAP) software used to calculate BER ratings contains a number of kinks that can potentially cause passive houses to be awarded perhaps unfairly poor scores, a topic covered elsewhere in this issue of Construct Ireland.

Manufactured by Austrian timber-frame experts Genböck and assembled on site by German builders in just two weeks, a generous amount of insulation and an impressive level of air tightness ensured the houses met the German Passivhaus Institut’s certification standard.

The 171m2 houses include four double bedrooms upstairs

A spacious kitchen / dining area on the ground floor

The external walls are a meaty 435mm thick, and include 160mm of EPS façade insulation, and another 160mm of rock wool. They boast a U-value of 0.10 W/m2K (well within SEI’s recommended figure of 0.175 W/m2K for passive houses), while the roofs have a U-value of 0.14 W/m2K. The first floor ceilings, with a U-value of 0.15 W/m2K, are insulated with 295mm of rock wool in two separate layers.

Intriguingly, two inches of concrete was laid in the first floor. Tomás O’Leary of MosArt architects consulted on the project. O’Leary himself built Ireland’s first certified passive house in Wicklow, and he explains this use of concrete: “There can be a perception that timber frame is noisier, and the concrete reduces noise penetration. It adds a bit of thermal mass too, which is beneficial in terms of preventing overheating. It also gives quite a solid feel to the floor upstairs. It’s quite unusual though.” Fergus Joyce adds: “I’d say they’re the only timber frame houses in Ireland with concrete in the first floor.”

The generous level of insulation was somewhat necessitated by the orientation of the buildings, which means they can’t take full advantage of natural sunlight for passive heating. “The front of the houses face north east,” Joyce says. “The sun is at the back most of the day. We bought the site with pre-designed plans, so in terms of orientation we built what we were given in the drawings.”

Tomás O’Leary elaborates: “It isn't the optimal orientation, and they don’t have the perfect elevation either, but that should be encouraging for the market. There might be a preconceived idea that you absolutely have to be facing south if you want to reach passive standards, but this proves that’s not the case.”

“Fergus mightn’t have needed to put in the extra insulation if they had been optimally orientated, but it's fortunate that we could achieve the standard without the perfect orientation. You can get up to one third of your space heating requirement from the sun if windows are pointing in the right direction, so there's a bit of lost potential there, but because of the high spec of the build and the good level of air-tightness, they were able to achieve the standard. It's about proper detailing.”

Indeed, perhaps what’s most encouraging about the Killerig houses is that they reached and exceeded the certification criteria without the ideal orientation or extraordinary levels of insulation, and based on existing designs that were never intended to be passive. The building regulations set to be introduced here in 2010 should come within touching distance of the passive standard, while the European Parliament has proposed that all new buildings within the EU be passive from 2011. While a mandatory passive standard may have once been seen as a pipe dream for green building enthusiasts, the Killerig houses prove that it is a realistic target.

The orientation also prevented the use of renewable energy: “It's quite the norm to use solar thermal panels on a passive house,” Tomás O’Leary points out, “but these houses didn't have the right orientation and therefore it didn't make sense.”

“The great thing about the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) software,” he adds, “is that you can test the specifications with the software to see if it meets the standard, and if it doesn’t you can test remedial measures like extra insulation to compensate for sub-optimal orientation.”

The windows, supplied by Genböck, are triple glazed, triple sealed and argon-filled with 12mm between glazings, and boast two low-e coatings, giving them an overall U-value of 0.87w/m2K, though some scored as low as 0.78w/m2K.

Genböck, triple glazed, triple sealed and argon-filled windows

Both houses are fitted with Drexel & Weiss Aerosmart M mechanical ventilation heat recovery (MVHR) units, which draw warm, stale air out of the kitchens and bathrooms and use it to heat up cooler incoming air, which is then passed to every room through insulated ventilation ducts. Up to 85 per cent of the heat energy from outgoing air is transferred to incoming air. If an additional temperature boost is needed on cold days, or hot water is required, a small back-up air-to-water heat pump kicks in. Air in the houses is changed about eight to twelve times a day, and the MVHR systems provide for all hot water needs.

The Drexel & Weiss units were supplied by Control Aer. The company’s director, Mark Sherlock, offers some background on the system: “It’s installed all over Germany and Austria in passive houses. It’s tried and tested. There’s only a small electrical demand, and it supplies heat at a fairly constant temperature.”

Damien Mullens of Eco NRG (now Heat Doc) installed the systems, and worked on the whole-house ventilation designs in conjunction with Drexel & Weiss. He explains: “The unit recycles heat within the houses. Stale warm air is extracted from bathrooms and kitchens, and passed over an air-to-air heat exchanger. After that the outgoing air is at about 5 - 10oc. More heat is extracted from the remaining air using a small heat pump, which cuts in and out depending on whether it's needed. It’s a plug and play unit. For a 1300 watt output you're using 375 watts of electricity, so it has a COP of 4.6.” Having also installed the ventilation system in Tomás O’Leary’s house, Mullins now has the distinction of having worked on every certified passive house in the country. “I only copped it when I was installing these systems,” he says.

“There’s no radiators or underfloor system,” Tomás O’Leary adds. “The heat is simply supplied via ventilation ducts into the air. There's quite a lot of evidence that passive houses have excellent air quality, they've done monitoring on the air quality in my own house, and there's lower CO2 levels compared to a standard dwelling for example.” The sitting rooms at Killerig also boast bioethanol-powered Planika fireplaces, widely used in passive houses, though their main function is ambiance rather than heating.

As you would expect with passive houses, detailed attention was paid to air-tightness, as Tomás O’Leary testifies. “They are extremely well constructed houses. They passed the blower door test on day one, and well surpassed it. They had to pass 0.6 air changes per hour at 50 pascals, but they got 0.4 on the first go.” O’Leary believes this is a testament to the precise craftsmanship that prefabrication allows. “It's an endorsement of the kit building approach. When the construction is done off site in a factory it's easier to get good quality,” he says.

“It’s all about insulation and air-tightness,” Fergus Joyce adds, succinctly capturing the remarkably simple yet highly effective philosophy of passive house design: If a building is generously insulated and extremely air tight, there’s little need to rely on elaborate systems, fossil fuels or even renewable energy for heating. A compact shape is also key to the passive house concept, as it reduces the area of the building from which heat can escape. Indeed, the simple cubic shape of the Killerig houses is one of their most noticeable features.

Ductworkfrom the MVHR a the house nears completion

The developer Fergus Joyce, of Botanic Homes, who is planning to proceed in building another eight passive houses this year on the Killerig site, as he believes that low energy homes will have an advantage in a slowing market

With two passive houses built, Joyce could easily be tempted to wait for the housing market to improve to build the other eight that are planned. “The market has completely stopped in this area,” he acknowledges. He’s not wasting any time though, believing that low energy homes will have an advantage in a slowing market. “We’re going to build the other eight this year. If there’s any sort of pick up at all I think these houses will fly out.” He’s conscious that if he waits too long to build the other houses, he could quickly find bigger developers moving into the passive house market and eliminating his competitive advantage.

While Joyce is new to passive houses, he is no stranger to timber. In his youth he left school to join his family’s sawmilling business, Wicklow Wood, one of the biggest in the country at the time. He later emigrated to England, where he established a business selling timber from a variety of mills - including his family’s own - to major DIY stores and builders’ merchants. He then began importing timber cabins from Russia. He returned to Ireland in 2000 and set up Botanic, first selling Russian timber cabins for use as chalets and garden houses, and then adding full-on timber frame housing to his repertoire. “We’re willing to consider any self build project, and will happily price up architectural drawings, including going up to the full passive house spec,” he says.

While the Killerig houses might only be the second and third certified passive houses in the country, dozens of uncertified passive houses have been built here to date. “There are costs involved because you have to do blower door tests and pay for certification. It can cost up to e1500,” Tomás O’Leary acknowledges. “But I'm of the view that it's important that as many as possible of the early generation of passive houses in Ireland are fully certified. We need to start off with a high standard.”

“The vast majority of passive houses around Europe are not certified. There is a potential problem if people are building passive houses but haven't designed them with the PHPP software. You'll hear stories about ones that didn’t work out so well. If you go for certification, you're guaranteed they’re going to provide comfort. In the end it's good for the customer and for the builder because they can be assured of the energy use.” O’Leary says that Fergus Joyce should be commended for making the brave decision to build passive houses in a country still largely unaccustomed to the concept.

Joyce explains why he opted for certification: “For me it means we can be certain that, to achieve the standard, these houses have been extremely well built. For me, that’s the most satisfying thing.”

The Killerig houses are only the second and third certified passive houses in Ireland, meeting the German Passivhaus Institut standards for heating demand and air-tightness

Project details

Main Contractor: Q-haus

Design consultants: Mosart

Timber frame and windows: Genböck

Heat pump/HRV supplier: Control Aer

Heating contractor: Eco NRG

Related items

-

Podcast: what we've learned from 20 years in green building mags

Podcast: what we've learned from 20 years in green building mags -

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal -

When is an A-rated home really A-rated?

When is an A-rated home really A-rated? -

International passive house conference kicks off

International passive house conference kicks off -

Iso Chemie Winframer gets BBA approval

Iso Chemie Winframer gets BBA approval -

New issue of Passive House Plus free to read

New issue of Passive House Plus free to read -

Software errors create false NZEB compliance picture

Software errors create false NZEB compliance picture -

WWHR an easy & costeffective route to Part L compliance — Showersave

WWHR an easy & costeffective route to Part L compliance — Showersave -

New Leeds developer goes passive

New Leeds developer goes passive -

Be ready for air testing of non-domestic buildings

Be ready for air testing of non-domestic buildings -

Architect returns to roots with A1 rated 'house of the people'

Architect returns to roots with A1 rated 'house of the people' -

Irish study group visits Germany on energy efficiency tour

Irish study group visits Germany on energy efficiency tour