- Passive Housing

- Posted

About the haus

Located in Oldtown, a hard to find country town in County Dublin, is a stunning new one-off house that not only manages to bring open-plan living to rural life, but also meets the onerous passive house standards using low impact materials. Jason Walsh visited the site as the house neared completion to find out more, an opportunity that Construct Ireland couldn’t pass up

The Oldtown property may only be German Eco Homes’ second house in Ireland, but it nonetheless manages to show progress in an unfamiliar market in more senses than one: “Our first house was in Naas,” said Hermann Richter, German Eco Homes’ managing director, “it was a low energy house but this one is a certified passive house, our first in Ireland.”

Based in Germany but with offices in County Kildare, German Eco Homes’ mission is to bring high-specification, low-energy housing to Ireland.

“Our company consists of two companies in reality,” said Richter. “My business partner, Roland Breunig, is based 50 kilometres from our German headquarters. He runs the architectural bureau. We also have our timber frame [manufacturing] company in Germany so the two came together.”

Richter explains that Breunig, like himself an architect and engineer, provides the planning service and that ten architects are employed in the office.

According to Richter, German Eco Homes is in an ideal position to capitalise on the changed nature of the Irish construction sector: “Mass production [of developer-led] housing is over [for the present time] but people are looking for individual houses and now they are looking for better quality.”

This is the exact scenario of the Oldtown house, a 300 square metre, two-and-a- half-storey dwelling built in a style that references modernism but with enough tradition in its design – notably the house has a pitched roof – to, if not blend in to the local built environment (such as it is – Oldtown is not exactly a sprawling metropolis), then to at least avoid the brutal aesthetic blunders that modernist architecture often stands accused of.

Richter explains: “The customer came to us and from the outset wanted to build a passive house. He wanted a turnkey specification, to have everything done by our company.”

Open plan living and extensive glazing to the south defines the living experience in the house

Timber cladding and a pitched roof soften the house's modern design

Given the call not only for achieving the passive house standard, but also for using high-specification ecological materials to create a finished product of exacting quality, it is remarkable that German Eco Homes is able to tout relative affordability as one of its benefits: “In terms of this one, we did it for e1,900 per square metre, excluding the foundation.”

According to Richter, building to the passive house standards in Ireland is highly advantageous. Indeed the basic requirements for a passive house are relatively simple: attention to detail in orientation and use of passive solar, good insulation, good glazing, heat recovery ventilation and, crucially, airtightness. However, it’s the mild Irish climate that makes things so much easier.

As reported previously in Construct Ireland: “As a result of differences in climate the passive house is actually something of a moveable feast: requirements in a relatively mild climate such as is experienced in Ireland are a lot less stringent than in colder countries such as Germany, Sweden or Austria. This fact has recently been spelt-out in detail in a new Sustainable Energy Ireland document authored by Tomás O’Leary.”

“It is much easier to build a passive house in Ireland than in Germany due to the climate,” Richter explained. “We could reduce the wall thickness, for example.”

Ireland’s temperate, maritime climate means that, despite our personal experiences being soured by horizontal rain, seemingly unending volume of moisture soaking us and the ever-present wind, Ireland does not see anything like the same degree of actual coldness as, for example, Germany which sees temperatures well below zero degrees Celsius, particularly in the east of the country.

Other differences include the fact thatin a colder climate water vapour resistance must be handled differently because in winter pressure will increase due to the difference between indoor and outdoor temperatures.

As a result of his experiences, Richter’s enthusiasm for passive houses knows few bounds: “It’s so easy to build a passive house here that Ireland should build all of its houses to the passive house standard.”

Despite the fact that passive houses have to attain higher standards in Germany’s colder climate, Richter has had plenty of practice getting them right: “Passive houses are rising in Germany, dramatically so in the last two years,” he said. “It relates to oil prices.”

Small windows minimise heat loss to the north; whilst large glazed sections to the south take advantage of passive solar gains, daylight and the scenic view

Small windows minimise heat loss to the north; whilst large glazed sections to the south take advantage of passive solar gains, daylight and the scenic view

In the past some people have worried that passive houses could face planning difficulties, primarily for two reasons: firstly, in order to maximise passive solar gain, passive houses work best when they have a south-facing orientation. Secondly, passive houses are often, though certainly not always, twinned with unusual modernist-inspired design that some planning authorities may balk at.

Richter stresses that the company will happily work with Irish architects’ designs, or from their own designs. “The advantage of our planning and design can help from a cost point of view because we can plan to a budget and avoid making energy expensive mistakes”.

According to Richter there were no such problems with the Oldtown project: “We planned this house ourselves and had good success with Fingal County Council. We got planning permission in six to seven weeks with no objections.

“The only problem was due to the windows being deemed too large at the south elevation, but we explained why this was necessary with a passive house.”

The house’s gable walls rise above the pitch of the roof creating what Richter calls a traditional theme. This device is also seen in the remarkable Bailé Glas development in County Cork featured in Construct Ireland in 2006.

Facing due south – the ideal orientation for a passive house – the Oldtown house overlooks the lush north Dublin countryside without dominating the landscape.

Inside, the house, soon to be featured on RTÉ’s hit show ‘About the House’, presented by top sustainable architect and ÉASCA founder Duncan Stewart, features four bedrooms, two upstairs and two downstairs.

As a closed panel timber-frame dwelling, the construction process was rapid. Richter explains: “We started with the ground-works on April 13. On May 16, the truck arrived. We started erection on May 19 and by May 21 we were waterproofing. Construction was completed.”

Interestingly, the client will not be moving-in immediately due to work commitments and so German Eco Homes are to rent the property back from the owner and will use it as a show home.

German Eco Homes' timber frame manufacturing facility in Schweinfurt, Bavaria

Cellulose insulation pumped into a closed panel wall in a controlled setting

Active or passive

Although German Eco Homes is seeking to promote passive houses, the company does offer alternatives to potential customers in the form of low-energy houses. Developed to a lesser energy-saving, though still high, standard, the company’s low-energy houses are slightly cheaper to build. However, in the case of the Oldtown house, it was passive or bust: “We generally do low-energy houses if the client’s plans can’t be rendered as a passive house. We do try to convince them to go up to passive standard because it’s most cost-effective,” said Richter.

German Eco Homes’ embrace of the passive house has resulted in interesting design challenges, something the company is happy to meet: “The key to any passive house is a compact design,” said Richter.

This doesn’t, however, mean that the house is actually small: “We cover 300 square metres with a roof of 160 square metres.”

Richter explains how this is different from how houses have been built in Ireland of late, particularly one-off dwellings in rural areas: “Other houses in Ireland cover 180 square metres [of living area] with 400 square metres of roof. They have a lot of surfaces which cool and they [therefore] cannot reach the passive house standard. As a result you also have to build a lot of walls and roof.”

The care and attention to detail paid at both the design and build stages is not necessarily obvious to the naked eye, but it unveils itself slowly as you move around the house. The same kind of generous thinking that leads the firm to embrace the passive house standard also led to all of the doors being wider than usual in order to allow wheelchair access – a touch that was not necessary, but certainly added no additional cost and is emblematic of a long and broad thought process.

The ceiling between the floors is solid timber: “It’s the best thing for sound insulation,” said Richter. The internal timber used in the flooring is spruce, and like all of the wood throughout the house, is Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified. Above this is a noise reduction layer, a polystyrene layer to hold the pipes and a cement screed.

The staircases between the ground and first floors and the first and second floors are a unique, virtually free-standing design that German Eco Homes’ supplier has patented. The staircases, and the floors, are FSC-certified oak.

All glazing used in the house is triple-glazed: “It’s krypton filled,” said Richter, “and the pane is thinner than normal so we can reduce the frame.” This has the result of providing superior thermal performance without ungainly and unsightly window frames. The glazing has a U-value of 0.5W/m2K while the frame has a U-value of 1.1W/m2K. Together this means the window units as a whole achieve an excellent U-value of 0.8W/m2K.

The house also features an intelligent home monitoring system that connects to the internet, allowing monitoring and control of the house – including the shutters that come down over every window – to be controlled remotely.

The attic space is a beam-supported open space complete with parquet flooring that will not only hide the servers for the control system but provide a storage space. Planning restrictions mean that it cannot be used as a bedroom as the house is designed to be two storeys in height, not three.

Preparing for the structure to arrive

The houses’ walls have a reinforced gypsum plasterboard on the inside behind which is a service cavity layer filled with hemp or wood-fibre insulation. In the case of the Oldtown house, both wood-fibre and hemp used: “We have 240 millimetres of cellulose insulation,” explains Richter. “We’ve been doing these houses since 1995 [and] I think it’s the best material you can use – it’s loose and it’s blown-in.

“Cellulose can take moisture and dry out – it’s breathable”.

Before the cellulose, a 50mm USB panel acts as an airtightness layer, and aslo as a vapour break. “It’s more breathable, open, stable and durable than the plastic foils that are normally used in air-tight houses”. Richter said. “We use special tapes and seals including Siga and Pro clima, which is critical in ensuring that the highest levels of air-tightness are achieved.

“On the outside we’re using a Pavatex Isolair insulating, waterproof, wood-fibre board. There’s a Tyvek membrane on top of that, two layers of batten creating a cavity for ventilation and, finally, a cement fibre board which is [then] plastered.”

The wall systems finish-up with a U-value of 0.15W/m2K.

“The roof is the same but without the service cavity,” he said.

“The floor is 250 millimetres of concrete and 10 centimetres [100 millimetres] of insulated conduit, 15 centimetres [150 millimetres] of insulation and a cement screed. In this case we used polystyrene and polyurethane [insulation] because there was no other suitable ecological material on the market.”

Richter stresses the fact the constructional timber – FSC certified pine – used in the building is not treated with toxic chemicals, a matter of principal for the company.

It’s not just Richter that thinks the house is of a high standard, though. Consulting engineer Michaél Galvin of Envirobuild and Associates Ltd. thinks so too: “I was doing the airtightness testing. It met the German standard by achieving 0.58 air changes per hour at 50 Pascals,” he said.

“It’s pretty remarkable in terms of airtightness, The figure is very good and it’s the first time I’ve seen when no re-work has been required.”

The solar thermal array provides water heating for the house

A timber element is both shelter for the front door on the north elevation and architectural statement

According to Galvin, this is a sign of German Eco Homes’ expertise in the field: “That kind of thing only comes with pure experience. It’s all about attention to details – this was considered normal just as we consider a block being levelled normal.”

For Galvin, the house offered the opportunity to see how things were done by continental Europeans: “I’m familiar with Super-E in Canada,” he said, “and have worked with them so I was keen to work with German eco people – I know they’re very good.”

Energising ideas

As always with sustainable dwellings, the heating system is of central importance. In this project, the heating system contains two main elements: firstly, and crucially, appropriate passive design means that solar gains are maximised and heat-loss minimised. Secondly, the still standing previous house on the site, which will in all likelihood become a storage area, has an oil heating system.

In all passive houses heat-recovery ventilation (HRV) is used, and this house is no exception with ventilation running above the floor on the first storey, but, as Richter explains, things are done a little differently. “It uses heat-recovery ventilation without an additional air heating unit to recover heat from the air.

“You also have the [environmental] impact of electrical energy, which would bring the house down to a B-rating.”

As it stands, the house is on-track for an A2 building energy rating (BER) but discussions are underway about attempting to achieve an A1.

“The house requires fourteen kilowatt hours of energy per square metre per year,” said Richter.

In theory passive houses in Ireland do not actually require a space heating system but many have them anyway, taking a ‘belt-and-braces’ approach to design safety.

“The customer didn’t want a stove so we decided to use an underfloor heating system connected to a 750 litre water tank,” said Richter. “This is heated by the 7.5 square metres of solar panels on the roof. It could [easily] be expanded to fourteen square metres to meet up to sixty per cent of hot water demand and potentially more.”

When used for space heating, the hot water is designed for efficiency: “We run a very low temperature through the underfloor system – 30 degrees – the pipes are close together.” Richter said.

“Solar gains [alone] could cover 40 to 50 per cent of the house’s heating needs. The final solution was to think about a wind turbine – this would bring us to an A1-rating,” he said.

“One alternative [to a turbine] could be possibly to build a small combined heat and power (CHP) unit. That could also cover the heat demand for the existing house and [even] the neighbour. That could be bio-diesel, gas or pure plant oil.” The client is also considering photovoltaic.

Richter has, in the past, experimented with other heating options: “We did some houses with heat pumps in Germany but we decided against it to more easily achieve an A rating. Besides, we believe you should reduce energy demand so that there’s little need for a heating system - for the convenience of the customer it’s better.”

Perhaps that could be his motto – a lot of hard work went into the Oldtown house, but ultimately it was all worth it: for the convenience of the customer.

Selected project details:

Architect: Breunig & Richter

Contractor/build system: German Eco Homes

Energy consultant: Envirobuild & Associates

Solar system: Wolf

Cellulose insulation: Isocell

Hemp Insulation: Thermo hemp

Air tightness seals and tapes: Isocell,

Pro clima & Siga

- Articles

- Passive Housing

- Passivhaus

- German Eco Homes

- Oldtown

- Low Energy House

- insulation

- FSC Timber

- cellulose

Related items

-

Unilin Ireland launches embodied carbon report

Unilin Ireland launches embodied carbon report -

Ecological launches Retro EcoWall for internal wall insulation

Ecological launches Retro EcoWall for internal wall insulation -

Xtratherm name changes to Unilin

Xtratherm name changes to Unilin -

Ecological Building Systems launch Retro EcoWall for internal wall insulation

Ecological Building Systems launch Retro EcoWall for internal wall insulation -

Podcast: what we've learned from 20 years in green building mags

Podcast: what we've learned from 20 years in green building mags -

Kore launches low carbon EPS

Kore launches low carbon EPS -

Kilsaran gets NSAI cert for EWI to steel frame

Kilsaran gets NSAI cert for EWI to steel frame -

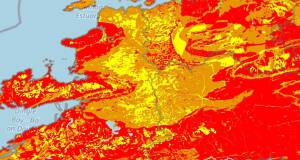

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal -

Steico offering free wood fibre insulation samples

Steico offering free wood fibre insulation samples -

Top 5 questions about specifying structural thermal breaks

Top 5 questions about specifying structural thermal breaks -

Major new grants for retrofit & insulation announced

Major new grants for retrofit & insulation announced -

How will we decarbonise heating?

How will we decarbonise heating?