- International

- Posted

International selection - issue 13

This issue’s selection includes a Chinese apartment block, Finnish social housing, an ambitious New York retrofit, and a German passive house district

Passive House Bruck, Zhejiang, China

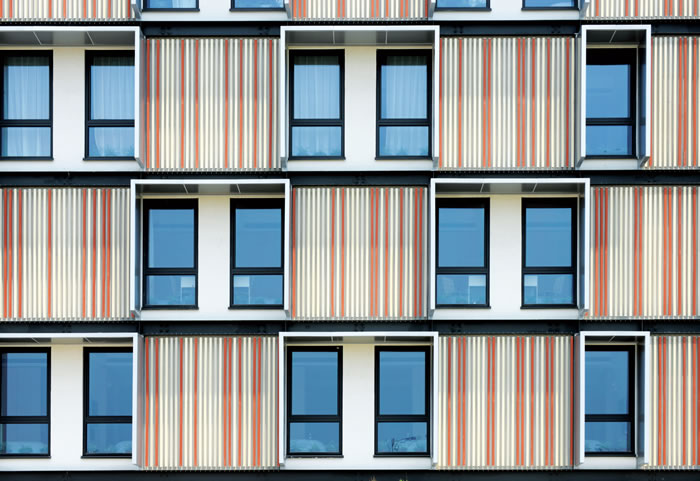

Located in the hot and humid south of China, Passive House Bruck has to cope with outdoor temperatures that top 40C and humidity regularly above 90%. These were among the central challenges for designers Peter Ruge Architekten. The building was commissioned by the Chinese Landsea Group, a private developer eager to experiment with sustainable building systems. Completed in the summer of 2014, the five-storey building houses a total of 36 one-bedroom apartments, six executive suites and four threebedroom ‘model’ flats, which are open for interested families to live in for short periods, to experience living in a passive house.

The building was constructed with lightweight concrete that was then externally insulated with polystyrene, and clad with vertical terracotta bars that provide shading. The building features three heat recovery ventilation units plus a heat pump system that delivers heating, cooling and dehumidification. There’s also 66 square metres of solar thermal panels that deliver hot water to the apartments.

Passive House Institute founder Dr Wolfgang Feist spent a night in one of the model flats, and commented: "A very large part of the global construction activity is currently taking place in China; consequently, it is all the more pleasing that the advantages of the passive house standard are also being recognised here.”

Passive House Bruck is the first certified residential passive house in southern China, and according to its architects, it achieves an approx 95% energy saving compared to conventional Chinese dwellings.

Photos: Jan Siefke

Bahnstadt passive house district, Heidelberg, Germany

Bahnstadt is a new passive house district on the site of a former freight yard in Heidelberg, south-west Germany. In 2010, the city council mandated that all buildings constructed here must meet the passive house standard (though some exceptions are allowed).

Bahnstadt covers 116 acres on the banks of the River Neckar. It is one of Germany’s largest urban development projects, and the largest passive house district in the world so far. The local energy agency models each new building in PHPP, the passive house design software, to make sure it meets the standard.

To date 150,000 square metres of floor space has been constructed, including apartments, student accommodation, a hotel, day care centre, shops, offices and labs. Another 150,000 square metres is now in the works.

All of the district’s heating and electricity is supplied by a wood-fired combined heat and power plant. Sustainable transport is easy here, too: the district is near the city centre, train station and tram network, and has welldesigned walking and cycle paths.

In 2014, the average energy consumption for space heating across Bahnstadt’s 1,260 residential units was 14.9 kWh/m2/yr — remarkably close to the passive house standard of 15. And once it is fully developed, up to 12,000 people will be living and working in this new city district.

Photos: Steffen Diemer & Christian Buck

Oravarinne passive houses, Espoo, Finland

Oravarinne – meaning Squirrel Hill – is the name of the suburban street in Espo, southern Finland, where these three colourful new passive homes were built.

The dwellings were a pilot project by TA Yhtymä, a social housing association, to see how well suited the passive house standard was to the region’s cold climate, and how practical it was to build them here.

The project showed that it is possible but “not yet the economic optimum”, according to its designers Kimmo Lylykangas Architects. ”For that, better products, especially windows, have to enter the market first.”

Indeed, meeting the passive house standard here demanded a super-insulated building envelope. The walls were constructed with reinforced concrete that was then insulated externally with 400mm polystyrene, while the attic features over 600mm of mineral wool. All the windows are quadruple-glazed.

Each of the buildings has a simple compact form — minimising the surface area from which heat can escape — surrounded by a terrace. The depth of the terrace varies depending on which way each facade is facing. For example, deep south-facing terraces provide shade in summer, but still let in the lower-angle sunlight in winter. Meanwhile, generous glazing provides views to the development’s wooded surroundings

Mamaroneck Enerphit, New York State, USA

This upgrade and extension to a family home in Mamaroneck, New York, was recently certified to the Passive House Institute’s Enerhphit standard for retrofit projects.

The original two-storey timber frame building was constructed in 1963. The upgrade, designed by AM Benzing Architects, involved removing the existing roof and constructing a brand new second floor. The entire structure was then externally insulated and finished with new ventilated cladding, while the new roof is insulated with cellulose (recycled newspaper).

A new south-facing timber pergola provides shade in the summer time while letting the low sun provide solar gain in winter. The renovated house is now heated and cooled by a Mitsubishi air-source heat pump, while a separate heat pump provides hot water, and there’s a new natural gas stove too.

The house has 28 rooftop solar photovoltaic panels now too, and the garage has a charging station for electric cars. There’s also mechanical heat recovery ventilation, as is standard for passive houses in cooler climates, which captures heat from stale air and uses it to preheat incoming fresh air.

Photos: Korin Krossber/PlanOmatic

Image gallery

Passive House Plus digital subscribers can view an exclusive image gallery for this article. Click here to view