Conscientious objection

Walter P. Toolan and Sons, a firm of solicitors in Ballinamore, County Leitrim has redeveloped its office with the intention of creating a healthy, environmentally sound building. Jason Walsh visited the office to find out more.

Originally a two storey terrace townhouse, the office of law firm Walter P. Toolan and Sons has been comprehensively re-imagined, refurbished and extended by Sligo based Colin Bell Architects as a model for a workplace that is healthy, pleasant and energy efficient.

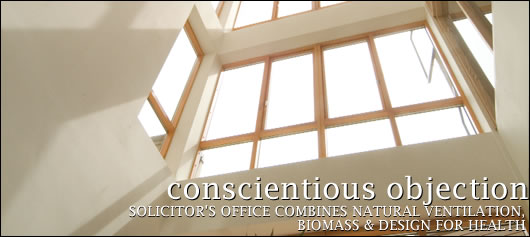

Totalling 800 square metres with an additional outdoor file storage area of 150 square metres, the office is not insignificant in scale, despite the modest – and tight – site. Three storeys at the front, the main reception area gives way to a central atrium. The building is extended south in two storeys and located directly above the reception is a series of cellular private office spaces necessary for the working of a law firm. The roof of the two storey building forms a roof garden while file storage and the boiler room are located to the south of the main building across a planted courtyard. On top of the file storage and boiler room is a small grass car parking area.

Planning and design of the office started five years ago but work really got underway in September 2005 when demolition started on the old building. The construction was completed in late December 2006 and the office occupied in January 2007.

The building's designer, architect Colin Bell, who has a masters degree attained at the Centre for Alternative Technology in Wales (conferred by the University of East London), was interested in using appropriate technology to create a workplace that was not only pleasant to work in but made incremental, yet significant, moves toward sustainability and energy efficiency.

His client, Gabriel Toolan, explains why he decided to think about sustainability when he was faced with the need to expand the firm's offices: "I've become interested in environmental architecture [over the years]. [An interest in locally sourced timber] was really the first step in this sort of thing," he says.

In fact, native sourcing became an essential ingredient of the new office building: both labour and, as far as possible, materials were locally sourced: "People are buying homes in far-flung places but I wanted to invest locally," says Toolan.

Taking his lead from the client's strong desires, Bell designed a natural ventilation scheme for the building to completely obviate the need for an inefficient, unpopular and apparently unhealthy air conditioning system: "With light and ventilation the question was, how would we ventilate this building naturally? A natural ventilation strategy was incorporated directly from the beginning," he says. Natural ventilation is the key energy saving technique used in the office building: "The idea is to pull air into the building and up a central void to create a stack effect," he says.

According to Bell, who heads-up a six person practice that includes a project architect and three technicians, a sound knowledge of ventilation is essential for any contemporary architectural practice: "The things that I learnt about ventilation were only one step ahead of what I did at college. Good architects should be aware of these kinds of things," he says.

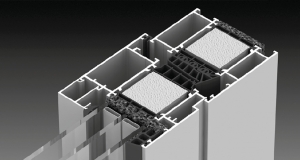

Due to noise issues the windows on the building's front elevation, which directly addresses the main street running through Ballinamore, are not openable. In order to bring air into the building acoustic ventilation boxes are set into the wall below the front windows. The boxes can be partially opened to increase airflow into the building without increasing noise levels, thus providing the initial ventilation.

The boxes themselves were made by Dickie Gabel Joinery. Gabel himself explains: "We made boxes that would take the acoustic units – we created a box protruding into the room with insulation to house the unit.

"Our objective was to create that kind of joinery. With the lid for the boxes we did some brainstorming to get it right – it had to be airtight so you didn't lose heat and then be openable to various different angles [to control the flow and quantity of air]."

Gabel says the job was not simple but the results were satisfying: "It was quite challenging – we hadn't seen anything like that [before] and we had to find the right materials so it would be practical and also look right. In the end we went for friction hinges – the same type that would be used in windows that can stay in position."

Obviously insulation is also vital in order to stop unwanted heat loss: "The insulation is the same material that window manufacturers use in non-glass panels, a high density foam," he says. Unfortunately for Gabel, this material was not readily available in Ireland: "It had no local supplier so we had to source it from Germany." The boxes also make use of an additional rubber seal."

Despite the unfamiliarity of the concept, Gabel was keen to move forward with the project and have his firm make its contribution. In fact, sustainable building is not new to the German-native Gabel: "We, as a company, mainly do furniture – reception desks and so on – but, personally, I've been involved in eco-friendly buildings for some years. I have a personal knowledge of materials and an interest in the subject."

Naturally Gabel has opinions on the relative merits of the Irish and German approaches to sustainable building: "What I still would criticise is that there is no body that monitors the way things are done. In Germany if you build a building someone checks it."

Nevertheless, working on the project has caught Gabel's commercial interest: "We've been thinking, if it's something that takes off, how can we develop it? Is there a way we can improve it? Achieving something like air-conditioning passively is a worthwhile goal," he says.

Building blocks

The structure of the building itself is composed of a steel frame. By choosing to build a steel frame instead of a traditional load-bearing wall construction, Bell has kept the long-term sustainability of the building in mind through flexibility: "We could have built it load-bearing [but] frame building gives you flexibility in terms of use. We should think about the use of buildings in 50 or 100 years," he says. The steel frame is combined with an inner leaf of block work built into it for thermal mass, and an outer leaf of block work.

"The outside walls are unlikely to be removed – though they could be – but the internal walls can be easily moved," says Bell.

Timber post and beam construction was considered but ultimately rejected: "A timber building wouldn't have had thermal mass," says Colin Bell. "A timber post and beam building would not have been able to support concrete floors and so we would have lost thermal mass," he says. "We chose steel frame because of buildability and economics." Fire regulations also played a part in choosing steel frame over timber.

The walls have a 100 millimetre cavity and are fully filled with polystyrene beads. Consequently, the designed wall U-value is not particularly far ahead of the building regulations requirements, but Bell chose the system with the knowledge that full fill insulation was likely to actually achieve the designed U-value.

Bell would like to have brought other factors into play in terms of sustainability, such as high levels of airtightness, but is satisfied with the end result as it is: "Ultimately airtightness is very important. In this case it wasn't included in the budget.

"Despite being quite a big office it doesn't have any air-conditioning. There's a huge energy saving as a result of that. At the end of the day, the quality of the building is very good. The quality of construction in ecological buildings has to be better [and] for that to be achieved time has to be taken [in design] and the builders have to take care. That should be reflected in the fees – you get what you pay for," he says.

"It would be really good to go back and monitor the building and I think the client will be open to that. I think that post-occupancy monitoring is a huge area in architecture."

As mentioned above, the building's front elevation, north facing, is three storeys in height, in keeping with the other buildings in the street and, indeed, the original building it is replacing. The extended rear of the building, facing south, is two storeys high.

"The north facing elevation had to be sympathetic to the street – there was no way we were going to get around that," says Bell. "Energy comes in further down the line. It's important but it wasn't the main motivation."

Clearly, for Bell, sympathy to the local environment, built and natural, is as important as the more typical mantras of sustainability. Indeed, prior to the interview, Bell took this journalist on a tour of local eyesores and dubious planning decisions which have seen building on marshy ground along the Shannon resulting, unsurprisingly, in paving and driveways subsiding.

Set against that kind of development, Bell's office for Toolans can be seen as a model: "We're not saying this is the be all and end all," says Bell. "It's moving in the right direction, though." Indeed, Bell's logic is flawless: it's better to encourage widespread uptake of as much sustainability as possible rather than focus on designing a few isolated showpieces.

According to Gabriel Toolan there was little or no useful research or support to draw on for the project: "We've taken on research and development which should have been done by a state agency," he says. Certainly, the project was privately funded and in receipt of no grant aid: "There was absolutely no state support to this project."

More than hot air

Heating is provided by a 75kW Bavarian HDG Compact multi fuel boiler supplied by Glas, running on wood pellets but capable of taking wood chip, located to the rear of the site beside the file storage annex.

Bell explains why specifically wood pellet was chosen as a fuel rather than, say, wood chip: "The client had a wood pellet boiler in his house and was happy with it and the contractor."

Despite their growing popularity, wood pellet and other biomass fuels can create unusual problems, particularly with regard to access and fuel storage: "There were a lot of teething problems in terms of getting the wood pellets working – getting the trucks in and so on – that we didn't anticipate," he says. "Thankfully, there is access."

Interviews were conducted for this feature in the summer of 2007 and so detailed fuel use information was not available at the time of writing. Indeed, by the time of publication the building will still not have been occupied through an entire winter. Nevertheless, Toolan is satisfied so far with the biomass heating system: "The heating is very good. Economically it seems to be comparable with oil."

Wood chip, more often used in commercial buildings than wood pellet, was considered but a decision was made to stick with pellets for the time being: "With wood chip you have to have a huge silo and you have to get a truck in to deliver it," says Toolan. Nevertheless, a change may yet be made for very practical reasons: Toolan owns an area of managed forest: "In the future we may change it to wood chip to be self-sufficient," he says.

"Radiators are used to give people individualised control," says Bell

Planting the seeds of tomorrow

Gabriel Toolan sees the key benefit of the new building as being one of health which, he says, in itself has a quantifiable knock-on effect on his business: "The increase in productivity that come from working in a healthy environment is immense. Colin [Bell] has done a lot of work on this."

One key aspect of the building's approach to healthy working is its approach to nature. A roof garden and a space between the main building and the file storage annex bring greenery into the eye line and a large indoor tree literally brings the outside in.

Jan Alexander of Pro Silva Ireland (prosilvaireland.org), who also founded Crann, an Irish environmental non-governmental organisation, selected the trees that grow on the site: "I think it's a subtle thing," she says. "I don't think people realise they feel better from having plants around them. I just know from my own experience that I am happier if I can see green."

Alexander is a forestry consultant with Pro Silva, a European network of commercial, 'close to nature' forestry. In terms of the workplace, she feels that having trees helps make for a more pleasant environment: "If you're concentrating on something your eye doesn't fall on the concrete wall, it falls on the tree beside it. They bring peace for the soul," she says. "If people really care about their staff it would be essential to have a lot of green in [a building]. The plants have to be happy so it just takes a bit of planning ahead."

Alexander chose what she calls a 'dinosaur theme' for the building's feature trees: "Two of them were around 270 million years ago. The Ginkgo Biloba was rediscovered twenty years ago in Japan. It had been thought to be extinct." The slow-growing Ginkgo Biloba is located at the rear of the building and surrounded by ground roses.

"The tree in the courtyard view from inside is a Woolamai pine. It was found in a remote gorge in 2003 in New South Wales [Australia]. It was also thought to be extinct," Alexander says. "The three storeys will help to draw it up. It's an Araucaria, it's related to the Monkey Puzzle Tree."

Finishing off the trees is an indoor tree, viewable from the main lobby: "It's a Norfolk Island pine," says Alexander. "It's a fast grower [and] in time it will fill the atrium. We wanted something that would wow people.

"Some people would say 'Why didn't you choose native trees?' I support native woodlands but with a building like this it needs to be a statement. It's a chance to bring the wonder of international trees in."

The building's use of wood goes well beyond living trees: the furniture and fit-out are largely timber and, notably, local timber.

"All of the joinery in reception is specially sourced native Irish ash and the front doors are sourced native Irish oak," says Gabriel Toolan. Toolan hopes to see the use of more native timber in buildings: "Joiners have a fear of it because it tends to move a bit. There is an ignorance in the timber industry of our native hardwoods."

For architect Colin Bell the use of timber – and its quality – is a vital aspect of the building's character: "I think it's a showcase in terms of what can be done with joinery rather than just carpentry," he says.

Ultimately a building's success is judged by its occupant. By this criterion, the Walter P. Toolan and Sons office has surely been a successful project. As Gabriel Toolan says: "It's brilliant – we're delighted with it. We did everything we wanted to do."

Selected project team members:

Client: Gabriel Toolan

Architect: Colin Bell Architects

Main contractor: Maxwell Construction

Joinery: Shannon Bros. Joinery and Clarke Cunningham Furniture

Planting & selection of trees & shrubs: Pro Silva

Construction of roof gardens & stone walling: Terry Grogan and Mike Vyvhal

Acoustic timber boxes: Dicky Gabel

Biomass boiler: Glas

Decking: CTS Ltd.

Roof garden: Alumasc Exteriors

- Articles

- Sustainable Building Technology

- Conscientious Objection

- colin bell architects

- joinery

- timber

- pro silva

- multi fuel boiler

- wood pellets

Related items

-

Timber in construction group holds first meeting

-

Mass timber consultation: have your say by 21 April to change the rules

Mass timber consultation: have your say by 21 April to change the rules -

Seeing the wood for the trees - Placing ecology at the heart of construction

Seeing the wood for the trees - Placing ecology at the heart of construction -

Boxing clever

Boxing clever -

TU Dublin launches timber technology degree

TU Dublin launches timber technology degree -

Scottish passive house built with an innovative local timber system

Scottish passive house built with an innovative local timber system -

Towards greener homes — the role of green finance

Towards greener homes — the role of green finance -

Timber frame & mass timber: the Passive House Plus guide to structural timber construction

Timber frame & mass timber: the Passive House Plus guide to structural timber construction -

Aru Joinery wins sustainable building award

Aru Joinery wins sustainable building award -

Ultimate Windows launches Olympia HI window

Ultimate Windows launches Olympia HI window -

Urban Front integrates passive pet flap in Oxford passive house

Urban Front integrates passive pet flap in Oxford passive house -

Trunk Low Energy Building launch new CLT business

Trunk Low Energy Building launch new CLT business