- Design Approaches

- Posted

Born again bungalow

Few words in the vocabulary of Ireland’s built environment come with more baggage than ‘bungalow’. For many people, it embodies a total disregard for good architecture and the environment, in part due to its association with isolated one-off housing. John Hearne visited a house in Mayo that mixes considered design with a host of modern technologies to breathe new life into the form.

The long, low bungalow was the staple output of the building industry in pre-boom Ireland. They featured little or no insulation, big leaky windows and long dark corridors that needed constant artificial light. Orientation was based on road frontage, layout never changed, and if there was any design, it had nothing to say about solar gain or prevailing winds. Bryck and Annette Robin’s house in Callow, County Mayo is a re-invention of the long, low bungalow, but this time, energy considerations are centre stage. “The planning stated that it had to be single storey,” says Robin, whose company, Rockingham Construction, built the house. “That was fine by me, I’m a real bungalow man.” Design-wise, the house is a little bit of his native Australia set into the hills of Mayo. “We wanted a long, colonial Australian design, but with a contemporary twist; good sharp lines, and loads of light.” Layout and orientation maximise solar gain, while a tightly sealed, highly insulated building envelope minimises thermal losses. Space heating comes from two wood pellet stoves in the open plan living area, while two separate heat recovery ventilation (HRV) units, both of which incorporate heat pumps, also assist in providing domestic hot water.

The site provided the construction team with its first challenge. The scrub covered hillside concealed what would turn out to be some of the densest rock formations in the country. During initial ground-works, they hit one huge rock which proved completely impervious to a 30 tonne rock-breaker. “So then we started in with a product called Dexpan,” says Robin, “because we didn’t want to go down the blasting route. We wanted something more controlled. They drill 20mm holes into the rock, and then pack it with this chemical that expands. You’re supposed to leave it for six weeks, but I left it for eight. It looked like it had done the job; the rock was all cracked on top, so I got the breaker back up again and he started chipping away at it, but it had just cracked the shell. Underneath was rock solid, and the chisel just bounced off it.” The supplier refunded the money spent on Dexpan, and Robin then paid double that for explosives. In the aftermath of the blast, it took a further three weeks with a rock breaker to level the site for the raft. “We’ve had students up here studying this rock, because it’s some of the oldest and hardest rock in Ireland. When you pick a piece up, you can feel it’s almost a third heavier than normal rock; it’s so dense and so hard.” Almost all of the rock was used subsequently to provide filler and in the landscaping and stone masonry around the site. In particular, Robin made extensive use of gabions – metal cages which can be filled with stone, then stacked, providing structural support without the need for concrete. “The county council insisted that we have natural stone walls, but I was determined that all the stone we used would come from the site. I went through four different stone masons before I found someone willing to work with what was here. I didn’t want to pay for that square, fake looking stone.” Eventually he found a local stone mason, James Devers, who was as enthusiastic about using the real thing as he was.

Facing south over Lough Callow, design and layout maximise both views and solar gain

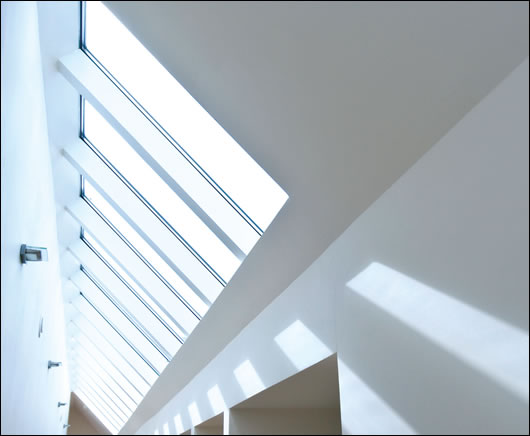

One of the key advantages of the site is its orientation. Looking south-south west over Lough Callow, design and layout maximize both views and passive solar gain without any compromise. House design was a collaborative effort with Paul Kehoe Architects (PKA). “Bryck and Annette were interested in a split level house,” says Rachel Chidlow of PKA. “By using a double gabled single pitch roof we were able to slide the bedroom accommodation behind the living accommodation so that the length of the building was to a scale appropriate to its site. Also, this allowed the height of the roof to be kept relatively low – again to keep in scale.” That concept – living to the front, sleeping to the back – maximises the solar gain in living areas, while the bedrooms have been kept small to make them easier to heat. That split level also facilitates the removal of the long, dark corridor. Twenty-four glazed panels run along roof, allowing light into both the corridor and the adjoining open plan kitchen/dining/living = room. “We thought about Veluxes,” says Robin, “and they’d have been good from a ventilation point of view, but they’d have been a nightmare to seal.” Working all of the energy solutions into the building at design stage was key to making them work. “We co-ordinated all the technology into the house,” says Childlow, “with a view to it fitting comfortably – enough space for the wood-pellet boiler, enough space for the ducts and so on, while at the same time making it feel like an ordinary house.” She says that there were some concerns around how the HRV would be worked into the design. Vaulted ceilings are vital to providing a sense of space, but don’t leave much room for ducting, while air intake and extract points break the smooth aesthetic of the ceiling. These issues were addressed by painting ceilings white to keep the vents inconspicuous, and setting the central beam as high as possible.

All the stone used in the landscaping and stone-masonry came from the site

This is a system built house. The Timber Frame Company in Wexford supplied a Kingspan TEK building system, which is based on structural insulated panels (SIPs). “I wanted it to be a warm house.” says Robin. “Myself and my business partner Aidan wanted to go down a different route to standard block work. He was doing a development of seven houses on his own site in Wicklow and we came across the SIPs, and it just seemed like a good idea. You have the one material and one envelope; roofs and walls all sealed together. We found it a lot cleaner. The panels come onsite, it’s all engineered, there’s no mess. Apart from the chimneys, I didn’t use any block work at all. So I went over to England and I did a course to become a registered fitter and learned how you do the sealing elements of the home in order to get it as air-tight as you can.”

The panels are composed of 110mm of high performance rigid urethane insulation sandwiched between two sheets of OSB. 1.22 m wide and up to 7.45m long, Robin stresses that these panels are very strong. “Around the perimeter and any low points,” says Robin, “you’ll have solid timber but thermal bridging is minimal.” There are no rafters. A steel beam runs down the ridge, and the panels sit from the beam to wall plate, with support from a solid timber post every 2.4m. These, says Robin, are the only real thermal bridges. Roof panels slot into a fillet of solid timber shaped to the correct angle running along the top of the wall panel. When jointing panels together, an ‘insulated spine’, which is a smaller version of the larger panel, is installed between the panels to ensure no cold bridging. Joints are then sealed with either a low expansion foam, or with silicone.

Vaulted ceilings in the bungalow provide a sense of space

The house was up and weather tight within two weeks. “I was running out of time on planning. Even though you get planning approval, you still have to build it within the outline timeframe. With all the rock problems, my planning was running out at the end of January, and we only blasted the rock just before Christmas, so I got the lads in over Christmas, we got the site leveled, the raft down and the timber frame arrived in the second week of January. We had it felted and battened in two weeks.” It should be noted that while this system was advanced when the house was built in 2004, the Timber Frame Company now no longer manufactures SIPs but has moved on to its own high-performance closed panel system, Synergy Home.

Robin points out that because the system is air-tight by design, there’s no need for additional air-tightness measures inside the panel. To bolster the thermal performance of the envelope, Robin chose a 37mm TW52 insulated plasterboard, bonded directly to the OSB, thereby reducing the U-value of the roof/wall envelope from 0.2 W/m2K to 0.18 W/m2K. “We didn’t want to look back across the lake to our own house and see another box on the hillside, we wanted something to fit in, and because the hill is wooded, we cladded it with western red cedar. But the planners objected to too much cedar cladding. They wanted more colored renders and we had to reduce the cedar by 50 per cent.” The cedar was supplied from sustainable sources by Machined Timber Services in Wicklow. Instead of a block-work outer leaf, Robin opted for Aquapanel cement board supplied by Greenspan. This system is estimated to have roughly 10 per cent of the carbon footprint of the conventional finish, and according to its NSAI Agrément certificate, has a design life of sixty years. The board is affixed to vertical battens on the outside, thereby facilitating ventilation through to the soffit on top. Once installed, the board is taped and jointed, then a base coat is applied, followed by a fiberglass mesh, a primer and finally a textured finish.

The chimneys rise on either end of the house, there to facilitate the wood pellet stoves, while also providing one of the house’s most striking features

Robin’s original idea had been to roof the house in corrugated iron – partly to capture something of Australian architecture, and in deference to the traditional use of corrugated iron in outbuildings in Ireland, but in the end the design team chose aluminium for roof, soffit and fascia. Supplied by Brian Smith of Alert Engineering, who also designed and built the bespoke flashings and hidden gutters, the roof requires no real maintenance and apparently carries a sixty year guarantee. It is screwed into counter battens fixed to the OSB at the back of the house, while at the front, the aluminium is held in place with hidden seam loc fixings from Tegral, providing a more streamlined finish. One of the obvious issues with an aluminium roof is sound transfer. “The SIPs panels are great for sound blockage.” says Robin. “A lot of people said the noise must be something else when it rains, but we don’t hear it. It’s loudest on the glass. I had the option of getting Tegral roof sheeting with the insulation on it in order to kill the sound, but I took the risk. I thought, with the panel so air-tight and so dense, there shouldn’t be a big sound transfer, and there wasn’t.” The roof glazing is 24mm Pilkington K Glass on thermally broken aluminium glazing bars supplied by City Glass in Dublin. It carries a U-value 1.7 W/m2K. Custom made downpipes are all stainless steel.

The chimneys provide the house with one of its most striking features. The only block work used in the project, these chunky blocks rise on either end of the house, anchoring it to the hillside, and giving the house the contemporary feel the design team sought. There to facilitate the two wood pellet stoves, they stand outside the conditioned space, each providing its stove with a 50mm independent air inlet at the base of the structure. They are capped with concrete, with the flue discharging through rectangular slots underneath the cap. “On the outside we also wanted the chimneys to be strongly expressed and to terminate the gables,” says architect Rachel Chidlow, “and to contribute to the articulation of the entrance. In this way the house also reads that it is heated by local fuel in the traditional sense.”

The smaller bedrooms also feature large patio doors which open onto the back of the house

Floor insulation comes from Kingspan’s TF73 Thermafloor laid directly under floor finishes and providing a U-value of 0.17 W/m2K. “The raft was poured with no insulation on it because I wanted all the insulation on top.” says Robin. “Thermafloor is insulation with chipboard bonded to it. It’s tongued and grooved and sealed together, and that gets laid on top of the raft, then sealed up to the TEK panel to keep the envelope solid.” Floor tiles and wide, planed semi-solid engineered board are fixed directly to the product. “We used a nice, big, black tile to soak up the sun. The floors never really get cold.”

The windows and doors, supplied by Seasonmaster in Mayo, are thermally broken aluminium with CareyGlass VistaTherm double glazing, carrying an overall U-value of 1.9 W/m2K. Very large windows to the front of the house provide plenty of passive solar gain, though there could potentially be an issue with overheating in summer. “If I had more time to design, I’d have gone for a shading element on the windows. I did come up with something, but in the end, we thought it was too commercial looking.” The units are all tilt and turn, allowing for secure, round the clock ventilation, while heavy blinds can be drawn on a hot day. In addition, one of the two HRV systems incorporates an air to water heat pump which has a cooling mode for use during hot weather. = The smaller bedrooms also feature very large patio doors which open onto the back of the house. “In terms of insulation,” says Robin, “that expanse of glass in the bedroom isn’t a great idea. Our thinking behind it was, because they were going to be small bedrooms, these doors provide an extension of each room. You’re straight out into the back.”

Builder and owner Bryck Robin at home and satisfied with the completed project

A Vanvex RS domestic hot water heat pump with an integrated 285 litre hot water boiler, extract air fan and heat pump was installed in the utility room located between the kitchen/dining and the living room. The unit, which is supplied by Genvex in Denmark extracts stale air from vents in the living spaces and delivers it to the heat pump. The unit is also fitted with a 1.5kW heating element if the pump can’t provide sufficient hot water.”The heat pump can supply 1000L of water at 45 degrees within 24 hours – that’s almost four cylinders, so we haven’t used the immersion at all; it ticks over fine with just the heat pump.” The unit carries a COP of 3.54 at an ambient air temperature of 15 degrees C. Maximum hot water temperature with heat pump is 55 degrees C, and with the electric heating element, that goes up to 65 degrees. This is a big unit, weighing around 300 Kg dry and almost half a tonne when full. It’s also a new unit to Ireland, and is not currently SAP Appendix Q listed, so the default applied in calculating the building energy rating under-rates the house substantially. The tests required by SEI to list the unit have been scheduled, but backlogs at test centres throughout Europe have delayed the process, and Robin is reluctant to complete the BER assessment until the certs are in place. He’s also awaiting the installation of a bypass unit onto the Vanvex system which will provide fresh air intake to the living spaces – currently, there’s only extract to the heat pump. The absence of fresh air intake in kitchen/dining/living areas isn’t ideal, but it hasn’t been a major issue so far because the house is open plan, and so living spaces are ventilated to a limited extent by the second Genvex unit, and of course by simply opening windows as required.

That second unit is a GE 315 VPC EC heat recovery ventilation unit consisting of a cross-flow heat exchanger, heat pump, cooling option, supply and extract air fan, F7 supply air filter, G4 extract air filter, and Optima 300 control. Installed in the attic towards the back of the house, this system is set up to extract from bathrooms and en suites and supply fresh air to bedroom areas. While the control systems for both units are intuitive and provide extensive control options, ensuring the right mix of intake and extract is tricky. “It’s a real balancing act getting it right, and it changes from winter to summer. You’ve got to fiddle around with the machines.”

Twenty-four glazed panels run along the roof, allowing light into both the corridor and the adjoining living areas

The larger of the two wood pellet stoves, an Extraflame Ecologica supplied by Kerry Biofuels, is installed at the base of the chimney in the dining room. “The Ecologica is quite big.” says Bradley Deutrom of = Kerry Biofuels. “It holds 35kg of pellets and in terms of efficiency, it’s anywhere between 86 and 91 per cent depending on the level of the pellet usage. On electrical consumption, the heating element is rated to 280 W but that’s only on for a maximum of 10 minutes. Running electricity consumption is 60W to 100W per hour. Fan speed and augur speed are dependent on the number of pellets coming into the stove – you can adjust those from levels one to five. The Ecologica is rated up to 11kW output.” The second stove, an Extraflame Comfort Mini has an efficiency rating of between 87 and 93 per cent, holds 12Kg of pellets and has similar electrical consumption data to the Ecologica. Both units feature electronic ignition, remote control, integrated thermostat and programmable weekly timer. “The Ecologica just ticks over on low through most of the winter.” says Robin. “We have a timer so it’ll come on say from 5am until 8am. During the day we rely on solar gain, and we wouldn’t tend to have it on in the evening.” The bedrooms were also fitted with thermostatically controlled convector plate heaters. Rated at 0.7kW, these units were installed primarily to provide peace of mind, just in case the low energy spec didn’t provide adequate heat. So far, they’ve hardly been used. “When my wife first moved in with the kids, she said this house is going to be freezing. I wasn’t completely sure whether it was or it wasn’t but I put on a brave face and said we’ll be fine. But it actually is warm. I mean you’re used to a stuffy, hot house with the rads pumping out heat, but I find in that house, it will keep 20 degrees in living areas, and in the bedrooms, the lowest they’ll get is down to about 15 or 16 degrees.”

Blower door tests arrived at an air change rate of 2.86 ACH at 50 Pascals. “I was delighted with the air test, especially with all the roof glazing…I don’t have many down-lighters – just in the bedrooms but they’re within the frame of the building, so they’re not a problem. I don’t have rafters and ventilation where normally you’d get drafts from down-lighters.” Surprisingly, the wood pellet stoves provided the main weakness in the envelope. “There was nothing coming down the flue, it was sucking air out of the fires themselves…I was a bit disappointed in that.”

Robin estimates that the low energy build added around 15 per cent to costs, but the build speed, as well as the degree of air-tightness achieved balance the cost equation. “You’ve got to look at other things. I was building this part time, so this is a quick way of doing it. It’s simple in its way; you’re using the same material throughout, and the shape of the house is actually quite straight forward. I wouldn’t say it’s idiot proof but once you know what you’re doing, if you follow that routine throughout, you won’t go wrong.”

Selected project details

Main contractor: Rockingham Construction

Architect: Paul Keogh Architects

Structure: The Timber Frame Company /Kingspan TEK

Windows: Seasonmaster

Floor insulation: Kingspan

Cement board cladding: Greenspan

Cedar cladding: Machined Timber Services

HRV: Genvex

Wood pellet stoves: Kerry Biofuels

- Articles

- Design Approaches

- Born again bungalow

- SIP

- bungalow

- Mayyo Callow

- passive solar gain

- Thermafloor

- Pilkington Glass

Related items

-

Steeply sustainable - Low carbon passive design wonder on impossible Cork site

Steeply sustainable - Low carbon passive design wonder on impossible Cork site -

Focus on whole build systems, not products - NBT

Focus on whole build systems, not products - NBT -

International - Issue 29

International - Issue 29 -

Passive Wexford bungalow with a hint of the exotic

Passive Wexford bungalow with a hint of the exotic -

The House of Tomorrow, 1933

The House of Tomorrow, 1933 -

1948: The Dover Sun House

1948: The Dover Sun House -

The dazzling Dalkey home with a hidden agenda

The dazzling Dalkey home with a hidden agenda -

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather -

A1 passive house overcomes tight Cork City site

A1 passive house overcomes tight Cork City site -

Norfolk straw-bale cottage aims for passive

Norfolk straw-bale cottage aims for passive -

Time to move beyond the architecture of the oil age

Time to move beyond the architecture of the oil age -

West Cork passive house raises design bar

West Cork passive house raises design bar